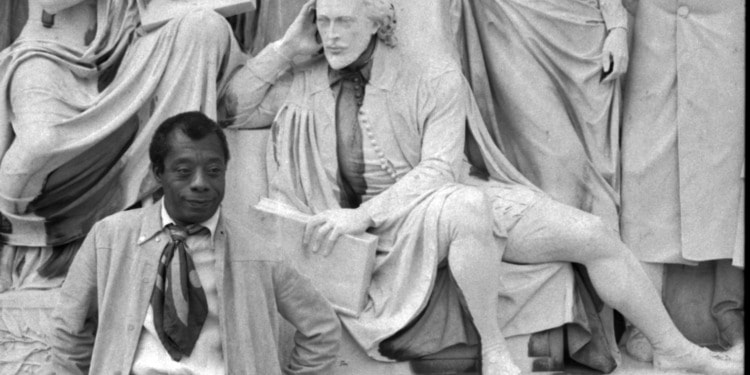

Photographs of the American writer James Baldwin, with his penetrating gaze suggesting curiosity, discernment, and wry humor, have suddenly appeared in my Facebook posts, reminding me how fascinating I have always found his personality.

Each photo is accompanied by an excerpt from his essays. I am a huge fan of prose style, and Baldwin’s is the best of the best — long, complex sentences full of wit and wisdom, with a startlingly contemporary analysis of what it means to be an “American Negro” (I will use his wording) applicable to today’s raging debates about Critical Race Theory, as I argued here on Impakter.

Where I live, we White American liberals are caught up in Racial Healing Workshops, eradicating racist microaggressions from our relationships, applying DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) standards in our workplaces, and reading up on personal, economic, and political disadvantages we have historically heaped upon Black Americans and from which we have reaped advantage and privilege.

After the resurrection of James Baldwin in my consciousness (I heard him speak in the 1960s), I rushed out to my library for an edition of his Collected Essays (Library of America). If you read this volume from start to finish, you will really enhance your wokeness, which means waking up to the status of Black people in America.

A prominent novelist, activist, and essayist of the civil rights era, James Baldwin was born in 1924 (d. 1987) and grew up in the Harlem ghetto of New York City, where he experienced the worst possible conditions for American Negroes:

“For the wages of sin were visible everywhere, in every wine-stained and urine-splashed hallway, in every clanging ambulance bell, in every scar on the faces of the pimps and their whores, in every helpless, newborn baby being brought into this danger, in every knife and pistol fight on the Avenue.”

By the summer that he turned 14, Baldwin “was icily determined — more determined, really, than I then knew — never to make my peace with the ghetto but to die and go to Hell before I would let any white man spit on me, before I would accept my ’place’ in this republic. I did not intend to allow the white people of this country to tell me who I was, and limit me that way, and polish me off that way. And yet, of course, at the same time, I was being spat on and defined and decried and limited, and could have been polished off with no effort whatever.”

Not letting other people define him while painfully trying to define himself became his lifelong quest to “keep the faith” with the truth of his situation.

Baldwin’s solution to the perils of a teenage boy in Harlem was to become a “child preacher.” This kept the pimps and drug dealers at bay, leaving him alone while they waited for him to realize that preachers could be corrupted by pimps and drug dealers. Plus, he practically lived in the public library and attended De Witt Clinton High School, where his teachers encouraged him.

In 1948, when he was twenty-four years old, he began the first of his many sojourns in Europe. He was very close to his family and friends, making the move a terrible wrench, but one that he found necessary to “keep the faith.” By leaving the homeland that filled him with anguish, he would be able to articulate that anguish from a distance.

The constant violence and discrimination in midcentury that American Negroes experienced created a general agreement among them that they could expect nothing good from White America.

In Baldwin’s analysis, white people were simply incapable of accepting Negroes as equals or affirming their essential humanity. This racial malevolence bolstered the delusional national narrative of an admirable American history, the story that white people had arrived in the colonies with their European values and ways of life and that those values and ways of life were still the norms for all Americans.

The problem is that American whites, from 1619 on, were accompanied by kidnapped Africans whose history has been embedded in the American story ever since, no matter how shrill white denial of that reality.

That is why today’s “White Christian Nationalists” cancel high school courses that include units on slavery, suspend teachers who teach them, and ban books from public libraries. Just this week, the Alabama House of Representatives voted to criminalize non-compliant librarians, while the Republican Governor of Florida, Ron DeSantis, is satisfied that “Florida is the place where woke goes to die.”

Each of James Baldwin’s Collected Essays can be taken as a step in his biographical quest for self-knowledge. That knowledge includes figuring out who he is from realizing who he isn’t.

For example, he is not a Black Muslim. In a movingly sensitive article about a visit to Elijah Muhammad at the Chicago headquarters in the early 1960s, Baldwin is sympathetic to the Nation of Islam’s goals of self-determination, self-respect, and separatism from white culture and impressed by the profound sense of self-worth the movement instills in its members.

“God is black. All black men belong to Islam; they have been chosen. And Islam shall rule the world. The dream, the sentiment is old; only the color is new. And it is this dream, this sweet possibility, that thousands of oppressed black men and women in this country now carry away with them after the Muslim minister has spoken, through the dark, noisome ghetto streets, into the hovels where so many have perished. The white God has not delivered them; perhaps the Black God will.”

But, he asks, how can these converts to the Nation of Islam become self-sufficient if they separate themselves out from the American economy, which contains the only possibilities available to them for financial advancement? On the contrary, he wants them to become full-fledged American citizens: “I am very much concerned that American Negroes achieve their freedom here in the United States” as Americans and as Negroes.

Later, when he and Elijah Muhammad’s disciple Malcolm X appeared on television shows together, Baldwin was taken to be the “integrationist’ (which he wasn’t) and Malcolm X as the “racist,” (which, in Baldwin’s analysis, he wasn’t either). Baldwin appreciated Malcolm’s gentle, non-egotistic personality and admired his passion for arousing Black people to pride in their full-fledged humanity:

“[H]e did not consider himself their savior, he was far too modest for that, and gave that role to another; but he considered himself to be their servant and in order not to betray that trust, he was willing to die, and died. Malcolm was not a racist, not even when he thought he was. His intelligence was more complex than that…”

Nor is Baldwin an integrationist, a fact which astonishes white liberals until we read his essays and realize that his skepticism is amply justified: Why, he asks, after all that Black persons have experienced from whites, should they want to “integrate” with us?

Although, in Baldwin’s day, describing American diversity as a salad bowl (with its implications that we each retain our ethnic/cultural flavor within the overall mixture) had yet to replace the “melting pot” idea that we should all melt into one “American” identity, Baldwin recognized the assimilationist undertone of “integration” and fiercely affirmed his identity as both entirely American and entirely Black.

Here is how he saw himself on the day he met Norman Mailer at a Parisian party in 1957: “I was then, a very tight, tense, lean, abnormally ambitious, abnormally intelligent, and hungry black cat” (click here to see video Baldwin Speaking c. 1963 on Being a Negro in America and denial of humanity, “demoralization”)

I had always thought that Black American ex-pats in Europe must experience significant relief from the tremendous stress and threat of being Black in America. But, as ever, Baldwin’s deft excavation of his own reactions illuminates the status of American Negroes in Europe as more complex. Though his time in Europe provided him with the peace and space he needed to write, it brought him even more insights about who he was not.

For one thing, he was not an “African.”

The Africans he encountered in Paris provoked a weird kind of shock to his identity: “Facing an African,” he experienced an “awful tension between envy and despair, attraction and revulsion. I had always been considered very dark, both Negroes and whites had despised me for it, and I had despised myself. But the Africans were much darker than I; I was a paleface among them.”

Related Articles: Failures of the American Education System: The ‘States’ Rights’ Myth and the History of Racism in America | Tackling Systemic Racism and Our Biases Through Empathy | Environmental Racism: Why Does It Still Exist? | 5 Resources Your Business Can Use To Fight Racism

Besides, they were deeply rooted in their home cultures and villages and bore themselves with the pride of knowing where they came from. American Negroes, in contrast, had been divided from tribal members on the auction block to keep them from speaking to each other and fomenting rebellion before being thoroughly “westernized” for centuries, leaving them extremely insecure about their identity.

Nor did Baldwin ever become “a Parisian.”

Although the heavy weight of racism was alleviated considerably in Paris, Parisians were implacably indifferent to his or any other ex-pat’s existence. “Of course, I think the truth is that the French do not consider that the world contains any nation as civilized as France.” They held Americans, whom they considered childish, in special contempt.

Baldwin’s American friends welcomed him in 1948 when he arrived with only $40 in his pocket and remained a source of solace, though he was uneasy with Black ex-pats who play-acted for whites and were suspicious of each other, alert less another Black interfere with or reveal their hustles.

The freedom from America’s plethora of racial stresses that enabled him to analyze those stresses so penetratingly marks his decision to return to America to take his part in the Civil Rights Movement as an act of special courage:

“In order to keep the faith . . . I came home, to go to Little Rock and Charlotte, and so forth and so on, in 1957, and was based in America from 1957-1970.”

Recognizing the perils faced by Negro leaders in the Civil Rights Movement, Baldwin chose to penetrate the very heart of darkness of American racism.

In the American south, Baldwin witnessed the resurgence of “white supremacy” in all its violence: he heard the screams of whites aroused to murderous hatred by Negro children trying to go to school, but he also “met some of the noblest, most beautiful people a man can hope to meet, and I saw some beautiful and some terrible things. I was old enough to recognize how deep and strangling were my fears, how manifold and mighty my limits; but no one can demand more of life than that life do him the honor to demand that he learn to live with his fears, and learn to live, every day, both within his limits and beyond them.”

Baldwin immersed himself in the racial turmoil in Little Rock, Atlanta, Montgomery, and Birmingham, producing journalism, giving speeches, and living out of his suitcase. From what he wrote when he returned to New York, we learn (not surprising given his extremely nervous temperament) that he had been frightened to death the whole time. He collapsed in a friend’s apartment where, for five days and nights, he re-lived every terror he had felt in the south while his friends and family frantically searched for him.

Baldwin was convinced that “What joins all people is the necessity to confront life, in order, not inconceivably, to outwit death: The price for this is the acceptance, and achievement, of one’s temporal identity.”

His tremendous personal courage was grounded in his lifelong goal to “take responsibility for my own experience.” His Collected Essays bear witness to the promise he made to himself that summer when he turned 14, a promise that he would rise up from the low self-worth foisted upon American Negroes for centuries:

“But at the bottom of my heart…I think that people can be better than that.”

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: James Baldwin on the Albert Memorial with statue of Shakespeare. Cover Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.