Updated 24 February 2019 with the news that Salvini is taking funds from Russia. Italy has a surprising weakness for populism à la Trump. It began over twenty-five years ago with Silvio Berlusconi and his Forza Italia party and is still going strong with the extreme-right populist Lega leader Matteo Salvini. Berlusconi and Salvini share the same worldview with Trump: a visceral attachment to national sovereignty (my country first!), a rejection of multilateralism and international cooperation in any form, and a determined anti-immigration and pro-business stance.

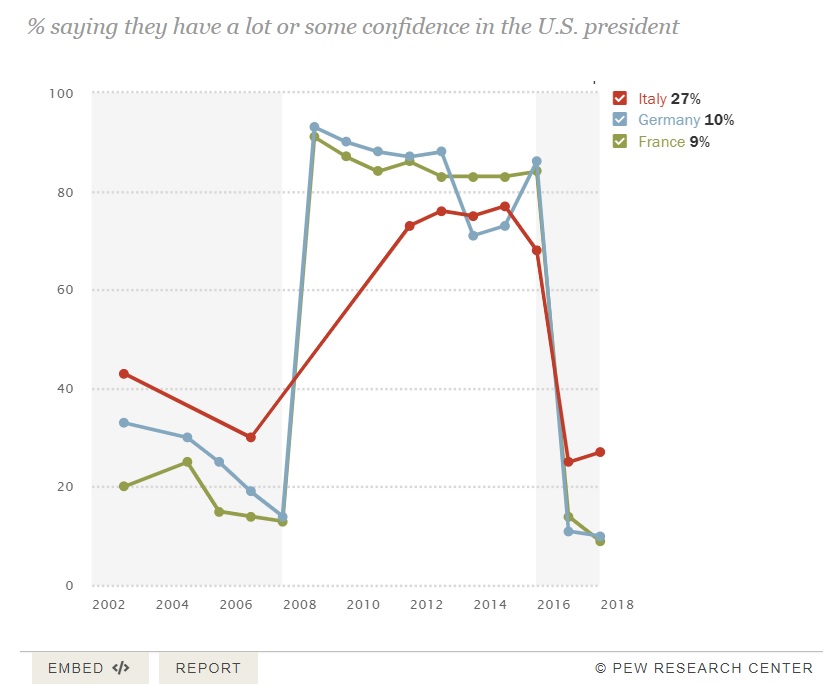

As to the Italian fascination with Trump, it is unique in the group of advanced, politically mature European countries that constitute the core of the European Union. Compared to fellow citizens in Spain, France and Germany, Italians are three to four times as likely to have “a lot or some confidence in the U.S. President”, as shown by a recent Pew Research Center survey (October 2018):

Trump does slightly better in the UK (28%), no doubt as a result of Brexit and Britain’s continuing “special friendship” with the United States. And, predictably, he does best in Europe’s most “illiberal democracies”: Poland (35%) and Hungary (31%).

Admittedly, Italy’s fatal attraction for strongmen is nothing new. Setting aside Mussolini and fascism and turning to modern times, we have Silvio Berlusconi, the TV mogul. Berlusconi has shaped Italian politics, opening the door to extreme right parties that were once banned because of their fascist roots. To understand how it happened and see where Salvini’s populism could lead Italy, it helps to look at his legacy.

Berlusconi’s Legacy: A Brilliant Start, Broken Promises and a Humiliating End

Much as Macron did with his party “La République En Marche”, Berlusconi created a party literally overnight, Forza Italia (“Go Italy” – note the nationalistic touch and the reference to Italy’s passion for football).

The start was even more explosive than Macron’s. Founded in December 1993, the party quickly gained a relative majority and won general elections three months later. That was the result of a skillful use of media campaign techniques on Berlusconi’s Mediaset, a near monopoly in commercial TV. The party’s earliest officials were Publitalia executives, the advertising arm of his business empire.

Forza Italia always was – and still is – Berlusconi’s “personal party”. And he proceeded to lord it over Italy, both as the head of the center-right coalition and serving as Prime Minister for a total of nine years. Considered the most influential politician since Mussolini, there is no question that he has shaped Italy’s politics and economy over two decades – unfortunately leaving the economy in shambles.

Yet he had vowed he would make his compatriots rich. Many believed him, seeing how rich he was himself. But Italy’s economic growth rate remained abysmal throughout. In 2010, only Haiti and Zimbabwe fared worse than Italy. Likewise, he couldn’t deliver on his promise to reform the slow and inefficient justice system, as his efforts at reform turned out to be personal moves to defend himself and his assets from prosecution. As to immigration, he was the first politician to tighten immigration rules in Italy and establish a special relationship with Libya to discourage inflows of migrants across the Mediterranean.

The most damaging result of the Berlusconi years was the return in mainstream politics of extreme right anti-establishment political parties, brought in and rehabilitated as Forza Italia’s partners: Umberto Bossi’s Lega (then called Lega Nord as it was both anti-Rome and anti-Southern Italy) and Gianfranco Fini’s National Alliance with deep roots in fascism.

2011, the height of the Euro crisis, was a turning point. In April, Berlusconi was put on trial, accused of paying an underage prostitute. By November, he was forced out of office. He left Italy in financial disarray, with an estimated debt of €1.9 trillion. He always claimed it was a “EU plot” by Brussels bureaucrats.

On 1 August 2013, he was convicted of tax fraud, banned from office and condemned to four years in jail that were commuted to “community service” due to his age (he was 77). In November of that year, the Senate expelled him from Parliament and he vowed to follow the example of Beppe Grillo, the comedian and founder of the 5 Star Movement, who was able to lead his party in spite of not being a member of Parliament Grillo has made it a principle in his party that anyone with a criminal conviction cannot hold a public office – himself included, since he was convicted of manslaughter in a car accident in 1981.

Today, at 82, Berlusconi is still in politics. Forza Italia has lost its luster and the Lega, that used to be his junior partner, is well ahead in the polls.

In the photo: Salvini and Berlusconi. That day, 7 January 2018, Berlusconi, Salvini and Meloni, the leader of Fratelli d’Italia, agreed on the distribution of electoral colleges Source: La Stampa, photo LaPresse

Is Salvini, Berlusconi’s heir, Italy’s Trump?

On 21 February, the Italian newspaper L’Espresso published shocking news: That Salvini’s party the Lega is likely to be secretly financed by Putin, to the tune of €3 million, with the goal of giving it a boost in the upcoming European Parliament elections and more generally spread discontent in Europe. This is of course not the first time that news emerge of Russian funding extreme-right, anti-establishment populist parties with the purpose of destabilizing Europe – notably Marine Le Pen in France is said to have received some €11 million from her friend Putin.

Yet the last ten days had been a turning point for Salvini with several wins. On 10 February, his party, the Lega, came first in local elections in the Abruzzo region, with 27,4% – a number oddly close to the one in the above-mentioned Pew survey rating Trump, suggesting that this could be indicative of the core support for any populist in Italy.

But what shocked Italians was the crushing defeat of the Five Star Movement coming in with a meagre 19.7%, far from the 33% it had won only eleven months ago in the national elections in March 2018. In fact, the 5 Star Movement – and its leader, Luigi Di Maio – has been down in the polls for months now, inching towards 20 %.

Meanwhile the leftist opposition party, the PD, is practically out of the picture in Abruzzo with only 11.1%. But perhaps these results don’t matter quite that much. Admittedly, the Abruzzo is a very small region (population 1.3 million), local elections are rarely in line with national ones and a lot could still go wrong for Salvini.

But then something else went right for him this week. The “Diciotti case” that had threatened him and risked sending him to jail got resolved in his favor with the vote in a Senate commission (“giunta per le immunità”), calling for maintaining his immunity from prosecution. A full chamber vote is to follow within a month and everyone expects it will go the same way.

For those who do not follow Italian politics closely, a word about the “Diciotti case” that exploded last summer – the first in a series of similar cases. Diciotti is the name of an Italian coast guard ship that saved 177 migrants, including many unaccompanied children,pregnant women and sick people in need of medical care.

Disallowing his own Minister of Transport who had let the ship to dock in an Italian port, Salvini reversed the order, thus going against the Italian Constitution, the European Court of Human Rights, international maritime law and elementary Christian charity. For five days, the migrants were blocked on board in dramatic conditions (no medical assistance, suffocating summer heat) while Salvini tried to obtain from EU member countries assurances that they would take them in.

A court case was brought against Salvini in Catania, in the section that examines cases against government ministers (“tribunale dei ministri”), and he was accused of kidnapping for the purpose of coercion, the omission of official acts and illegal arrest.

Salvini is essentially free now to focus on other matters at hand: Get approval to finish the massive infrastructure construction of TAV, the high-speed train linking Lyon (France) to Turin (Northern Italy) through the Alps; and to obtain increased administrative autonomy for Northern Italy.

Autonomy for Northern Italy is a demand from the historic base of his party and he cannot ignore it: Northern Italians are sick and tired of paying taxes that go to support Southern Italians. They want to break off from Rome.

Salvini vs. Di Maio: The 5 Star Movement’s Growing Weakness

The Lega is still the Lega Nord at heart. And they don’t like the 5 Star Movement’s pet project, the “reddito di cittadinanza”, citizen income, a form of UBI (universal basic income) that will benefit some 1.3 million poor families, mostly located in the south. The policy comes at a huge cost to the treasury, from €7 to €8 billion a year, and has been the source of difficult negotiations with Brussels over the planned deficit that exceeded EU budget rules.

These are the points of contention between the two partners and it is difficult to see how they could ever come to an agreement.

It’s the North battling the South.

The 5 Star Movement disagrees in principle on TAV, essentially for “green” reasons, a fear the train tracks will destroy the environment; and it cannot allow Northern Italy to withdraw from fiscal responsibility and stop paying for the proposed citizen income.

But principles in the 5 Star Movement are wavering these days.

First, a diplomatic row earlier this month with France escalated until the French Ambassador in Rome was recalled, something that hadn’t happened since the end of World War II. Only after Italian President Mattarella called Macron did the Ambassador return (after eight days). All because Di Maio expressed “radical” views on his blog in support of the Yellow Vests and, worse, met in Montargis (France) on 5 February Christophe Chalençon, a dangerous extremist who claims he has paramilitary forces to oust Macron.

Then, on 19 February, a web poll on Rousseau, the 5 Star Movement’s online platform, caused waves. Asking members whether they would support maintaining Salvini’s immunity against prosecution, 59% voted yes.

A stunning result given the attachment of Movement members for removing parliamentary immunity – a pillar in its historic fight against the establishment and the political “caste”. The episode also revealed the extent of the split among party members: 41% voted to lift Salvini’s immunity and allow the magistrates to prosecute him, and that’s not a small number.

Remarkably, Luigi Di Maio seemed oblivious to the consequences: “This is democracy!” he exclaimed after the Rousseau vote, “We allow our members to decide, we have been doing this for years. Our members decide and we carry on that line.”

This is not democracy. But then Di Maio is a clueless young man (32 years old) who has never studied History or Law and has no experience of government. For many observers, he lacked leadership in resorting to the Rousseau diktat instead of carrying forward the party’s principles.

Besides, Rousseau is merely an online platform – and hence relatively insecure and opened to hacking – and it is far from representing the will of the people: Compared to the 11 million people who voted the Five Star Movement last March, the numbers voting on it are absurdly small: 52,417 voted on the platform in the web poll on Salvini. That means the “majority” that voted to protect Salvini from prosecution amounted to exactly 30,948.

A digital platform on which only a limited number expresses an opinion – and moreover an opinion on a complex judicial question that requires expert knowledge – cannot, by definition, be democratic or just. Indeed, democracy, to function at all, needs institutional fixes to avoid the “tyranny of the majority”, the famous checks and balances between the three powers (legislative, executive and judicial) first proposed by Montesquieu and applied in the American Constitution over two hundred years ago.

What the 5 Star Movement is facing is moral collapse.

But all is not good and well for Salvini either. Not only does he need to deliver on the TAV and on autonomy for Northern Italy, but also on migration. He has promised to send all the migrants either back home or redistribute them among EU members, but that hasn’t happened. What is urgently needed is a reform of the Dublin regulations. His political partners in Hungary and Poland have pulled the rug under his feet: They have refused to take in the quota of migrants assigned to them and blocked any reform at the European Council.

Italy’s Damaged Image Abroad: The Salvini-Di Maio Government Under Fire

Italy is in a mess, and the mess is becoming highly visible abroad.

Against the backdrop of the France-Italy diplomatic row and the increasing isolation of Italy in the European Union, a recent speech at the European Parliament by Guy Verhofstadt hit a raw nerve. Verhofstadt is the leader of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE Party ) and former Prime Minister of Belgium. He spoke in the presence of Italian Premier Giuseppe Conti and laid bare the economic wreckage and moral waste in Italy that began, as he rightly pointed out, with Berlusconi:

Small wonder the video of his speech (which he gave in Italian, a smart move to ensure a wide audience in Italy) went viral across the country. Many Italians, mostly in the opposition, reacted in support but a sizable minority (no doubt the 27% of the Pew survey) expressed anger.

Yet people in the opposition were also shocked. Carlo Calenda, the PD politician and author of the bestselling Orizzonti Selvaggi (Wild Horizons, published in October 2018) who is trying to build up a new left in Italy was not pleased. He objected (on Twitter) to Verhofstadt calling Conti a “burattino (a puppet) in the hands of Di Maio and Salvini”. In his view, this is an insult to someone who is a Prime Minister.

How did Italy ever get to this point?

What Happens Next: Is Salvini the Big Winner?

The next local elections are due in Sardinia (population 1.65 million) and we may get yet another glimpse at the future. But the decisive electoral event remains the upcoming May elections for the European Parliament.

Salvini has already said the Lega won’t run with the 5 Star Movement for the EU Parliament. As to the PD, it is slowly recovering and Calenda has successfully launched a list for the European elections, SiamoEuropei.it, that could attract some 20-24% of the votes, as much as the 5 Star Movement.

The latest polls (21 February) show that the 5 Star Movement is in bad straits. If Italians voted today the Movement would garner only 21 percent of the preferences. The center-left, however, despite the decline in the PD (which stands at 18 percent) would get 22 percent. While the rise of the Lega continues, with 35 percent of preferences, making it for now the first Italian party.

The consensus for Berlusconi and other extreme right parties (like Fratelli d’Italia) has also increased (slightly) and is today at 15.5 percent. Together, Salvini and the right would get slightly over 50%.

Bottom line, Luigi Di Maio needs to realize he is facing a totally polarized electorate, split 50-50. Yet he still has a majority in Parliament. The smart move would be to dissolve the government, get a mandate to form a new government and seek new allies on the left. Allies that would be far closer to the 5 Star Movement’s heart than Salvini’s Lega could ever be.

Will Di Maio wake up? In any case, reality is about to catch up with him as Italy is now plunging into recession, turning his cherished citizen income project into a pipe dream. Yet another populist broken promise.

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE BY IMPAKTER.COM COLUMNISTS ARE THEIR OWN, NOT THOSE OF IMPAKTER.COM

Featured Image: Clouds over the Colosseum Source: Flickr.com Ed Z