On 31 May, Italian politics took an unexpected, spectacular turn. President Mattarella approved the very government he had vetoed – as was his constitutional right – four days earlier. Now the two big winners of the March elections, Luigi Di Maio’s Five Star Movement (M5S with 33 percent of the votes), and Matteo Salvini’s The League (17 percent) finally got what they wanted.

It had taken 88 days of hard negotiations to get there. And the unlikely alliance between an extreme right party (The League) with a centrist party (M5S) that has socialist roots (in the Partito Democratico, or PD). Both are populists and anti-establishment, The League with its base in Northern Italy and support from business, M5S with support from young people and the South and a fluctuating political platform shaped by social-media. Di Maio and Salvini had hammered a 56 page contract for a so-called “government of change” and selected as premier an unknown non-politician, the economist Giuseppe Conte.

What made Mattarella change his mind? Much of it appears to be the result of unexpectedly nimble political work on the part of Di Maio, who, despite his youth and lack of experience, is apparently endowed with unusual political instincts. Improbably, after insulting Mattarella and calling for his impeachment, he withdrew the accusations and instead met the President eye-to-eye. And was able to change his mind. The idea of a “technical” stop-gap government to prepare a return to the polls was abandoned and Conte came back with a new list of ministers.

What is remarkable is that the new list had only one notable modification: Paolo Savona, the Euro-skeptic 81 year-old economist Mattarella had objected to, was moved from Treasury where he had been originally assigned at Salvini’s request, to Minister for Relations with Europe.

An apparently slight correction but a significant one: Savona’s new position is much weaker than at Treasury, he is a minister without portfolio (i.e. without the support of a full ministry). The new man in the Treasury post is Giovanni Tria, a well-known economist with a long career both nationally and internationally – in short, a more moderate figure.

HAVE POPULISTS TAKEN OVER THE ITALIAN GOVERNMENT?

On the next day, the international press, even staid and serious journals like Bloomberg, reacted with emotional headlines: the Populists have surged to power in Italy! They will take Italy out of the Euro and Europe!

Despite the scary headlines, investors took it in stride, and even welcomed the “stability” that a new government implied, as the Wall Street Journal was quick to note. In short, they have set aside the likelihood that Italy will exit the Euro.

Yet, the new man at Treasury, Giovanni Tria is really not very different from Paolo Savona. He agrees with Savona on Europe and that a reform of the Euro is essential. On the face of it, pulling Savona from one key Ministry to another less powerful position seems like a gratuitous game.

How come markets are reassured by Tria and scared by Savona? What do investors know that the journalists don’t, what really happened?

THE REAL STORY BEHIND SAVONA’S REPUTATION

First, the scare over Savona was vastly exaggerated – almost a case fake news. Savona arguably was clumsy in managing his image: He didn’t come out early enough to clarify his position on the Euro and issued a communiqué only one day before Conte walked up for the first time to the Quirinale to meet President Mattarella and propose his list of ministers.

Worse, he allowed certain bits of news floating on the Net to muddy his reputation, turning him into a dangerous looking Euro-skeptic. Two things in particular worked against him:

- An Open Letter sent to former Greek Finance Minister Varoufakis in July 2015, signed by both Savona and former Italian Finance Minister Giulio Tremonti, on “the reforms to the EU that they considered necessary”;

- The rumour that he would actuate a “Plan B” to take Italy out of the Euro by stealth.

With the Open Letter, Savona publicly aligned himself with Varoufakis, the man most hated by Brussels and the “troika” (the EU Commission, IMF and European Central Bank) – mainly because Varoufakis attempted to stand up against the “troika” experts as they took over control of Greek public finances and imposed politically insensitive (and morally questionable) measures to solve the Greek debt – at the expense of Greece’s poor and middle class. As a result, Savona was branded a “euro-skeptic”.

With “Plan B”, it was even worse. Savona suddenly took on the semblance of a Trojan Horse, ready to assault Brussels from the inside and bring down the Euro and Europe. While a Brexit or a Grexit will shake the Union, and exit by Italy, being the third largest economy in the EU and a historic pillar of the Union, would kill it.

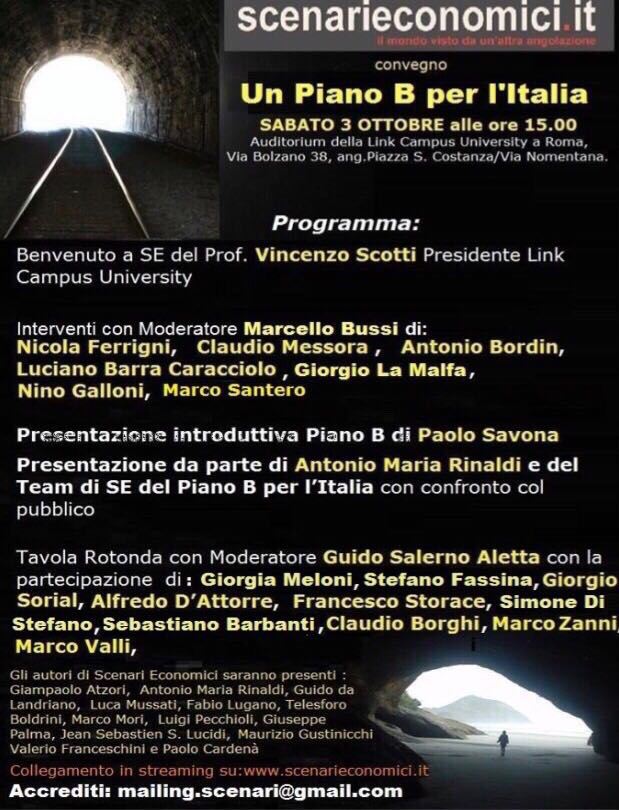

But the fact is this: Plan B was never the work of Savona. Other economists did it, he didn’t. He merely presented it a meeting of experts in Rome in October 2015, as announced on this poster:

In the photo: Poster for the 2015 expert meeting at which Savona introduced “Plan B”: this makes it clear that Savona never participated in the team that formulated Plan B. Other economists, not Savona, presented Plan B and led the debate on it.

Savona’s supposed and much feared “Plan B” was precisely that: a plan “B” that nobody intended to actuate, it was an academic exercise in which Savona did NOT take part. Savona’s preferred course of action, which he called “Plan A” was (1) staying in the Euro and (2) reform it so it would come out strengthened.

We need to be aware that in academia, it is normal to “think the unthinkable”. It happens not just in Italy, but also elsewhere, in particular in Germany.

The German press is full of horror stories about Italy notably when the EU Budget Commissioner Oettinger, a German national, “insulted” Italians and the EU Commissioner Juncker did likewise, unwisely suggesting Italians were lazy and corrupt. All this is also fueled by serious economists that, safely ensconced in their ivory towers, do not always realize the impact of their academic “exercises”.

The latest took place two days ago and was reported by Die Welt. The article is explicit: “Top economists are now thinking through the unthinkable in Berlin: strategies for a possible failure of the euro.” It was a meeting of “well-known economists” with the goal “to develop a contingency plan for a possible euro disintegration”. It seems the economists discussed “the costs and consequences of a potential collapse of the Euro” and considered “reforms which could facilitate withdrawal”.

Does that make all these German economists euro-skeptics? Of course not. But it doesn’t help that the article explicitly said their meeting was in reaction to the elections in Italy that have supposedly, in the words of Die Welt, “proved that the danger of a euro melt is anything but banned. There, the head of the right-wing populist Italian Lega, Matteo Salvini – after all one of the election winners – had announced that only death is immutable, a currency certainly not.”

In short, everyone in Europe is preparing a “Plan B” in case of Euro collapse – not just Italy.

WHAT GIOVANNI TRIA BRINGS TO THE EUROPEAN TABLE

Giovanni Tria, born in 1948, an economist with a first degree in law, is not a politician but he has a long experience in working close to government and international bureaucracies. He has even headed for several years the Italian school for Public Administration and he was worked with the UN agency ILO. He has ideas on all the issues of the day, including immigration, as shown in this video:

Readers who understand Italian will appreciate his pragmatism and broadness of views. I am convinced that this is a man capable of thinking through issues and coming up with workable solutions. An article published on the pro-business Sole 24 Ore in March 2017 clarifies his vision.

Again, on reading it, one can see that the analysis is spot on. Regarding Europe, nobody is right, he says. Those who call for exiting the Euro are wrong, but neither is Mario Draghi right when he says that the Euro is irreversible. In his view, Draghi’s famous assurance that he was ready to “do whatever it takes” to save the Euro, is not realistic. To become a solid currency like the dollar, the Euro needs to be sustained by two indispensable pillars: monetary and fiscal. So far, the Euro has only been given the monetary pillar, it now needs the fiscal one, starting with a strong banking union.

Eu institutions have not done enough, the Juncker plan is insufficient to relaunch the EU economy and neither is the European Central Bank’s policy of QE (quantitative easing). As a result, the real problem is a deficit in public spending.

The real problem, he points out, is that fiscal maneuvering is limited by the threat of a sovereign debt crisis, making it impossible to engage in deficit spending – a threat Italy is painfully aware of, with a debt of 132 percent of GDP. The solution he sees is “monetization of a part of the public deficits” without creating additional debt and controlling current expenditures, “to an extent compatible with a path of constant debt reduction.”

That should be music to Brussels’ ears. He is not calling for Italy to expand its debt, even if he accepts to implement the new government’s plans of deficit spending coupled with a flat tax and a “citizen’s income” – both expensive measures that are, he concedes, problematic.

In practice, with someone like Tria at the Treasury, one may expect to see some of Salvini’s and Di Maio’s plans to go through, in particular a lighter tax load on business to help re-launch the Italian industrial sector and more State help to the unemployed. But not all of it, and certainly not to the extent that EU regulations are flouted and the Euro is crashed.

WHAT NEXT: ITALY’S NEW ROLE IN EUROPE

The new Italian government is set to go to Parliament next week and obtain approval. On its own, it can count on about 50 percent of the votes, and it should get support from Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (14 percent). Berlusconi however is likely to act as a break and join the opposition should the government adopt anti-European policies or engage in fiscally risky measures causing the famous “spread” to soar (at the time of writing, it is at a comfortable 223 points – far from the 575 points that caused Berlusconi to resign in 2011).

In short, Italy may have a “populist” government, but it is restrained and has nothing to do with illiberal democracies like Hungary or Poland.

For the new Italian government, a constructive European response to the immigration crisis – including a strengthening of Frontex – and serious Euro reform will be paramount.

Expect Italy to push for a “European plan of public investment” to re-launch infrastructures, energy, R&D, security and jobs. The plan would require a yearly amount equal to at least 2-3 percent of the Eurozone GDP and should be carried out within EU structures – not outside. For Tria, it could be guided by the European Central Bank

This is both reasonable and revolutionary. For the first time, Italy would make itself heard in Brussels with its own plans, instead of merely acquiescing (as it has done so far).

It also happens that Tria’s ideas align themselves with Macron’s plan for EU reform.

That could make for a watershed moment: For the first time, Italy might enter the big European game side-by-side with France, displacing the famous Franco-German alliance that has guided Europe so far. Macron and Merkel are friends, of course, but they will need to open up their duo to Conte and his finance minister, Tria. And for the first time, Germany could find itself in the minority: France and Italy together weigh much more.

Will Italy catch this opportunity to make European History?

Editors Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com

Featured Image Credit: Salvini February 2015 Italian right-wing leader says Facebook blocks his personal page _ Reuters/Max Rossi