If you had traveled to the Middle East as a professional journalist or an independent filmmaker, we would have probably been investigating the mysterious story of your disappearance. Otherwise, you should count yourself lucky if you are reading this article now. In fact, travelling to this area as a journalist or an independent filmmaker is something like the “Adventures of Tintin”. By entering the Middle East you step into a region which is well-known as the world’s biggest prison for journalists and media activists. And Iranian cinema is part of that story.

According to a recent Amnesty International’s report, this region consists of some of the worst countries offending human rights. At the same time, one of the largest energy resources of the world lies in this area. Even if you had not vanished or been jailed, you would probably be banned like Jafar Panahi: He is the Iranian independent director whose films were banned in his homeland and yet he successfully grabbed international attention with one of his films, “Taxi”.

Jafar Panahi’s Taxi takes a long route in Iran: from pre-modern to the post-modern era. But how does this route go?

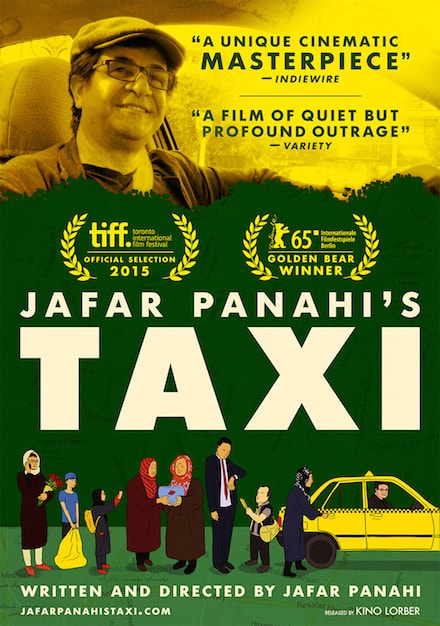

In the Photo: “Taxi” by Iranian director, Jafar Panahi, is a showcase of the power of cinema

Pre-modern Era 1930s – 40s

From a sociological perspective on communication and mass media, there are three periods of time: pre-modern, modern and postmodern. This classification indicates the type of medium of communication and the level of modernity in society and it should not be confused with concepts of Art or political modernism.

In the pre-modern era, the media was just limited to newspapers and radio. It took a long time for people in the Middle East to experience cinema as an entertainment device while it already was prevalent in France thanks to the Lumière brothers. It should be noted that when the cinematograph appeared in Iran, the first oil wells were also explored. So the Iranian government, able to access huge financial resources from oil revenues, felt empowered and started to misuse the cinema as a propaganda tool.

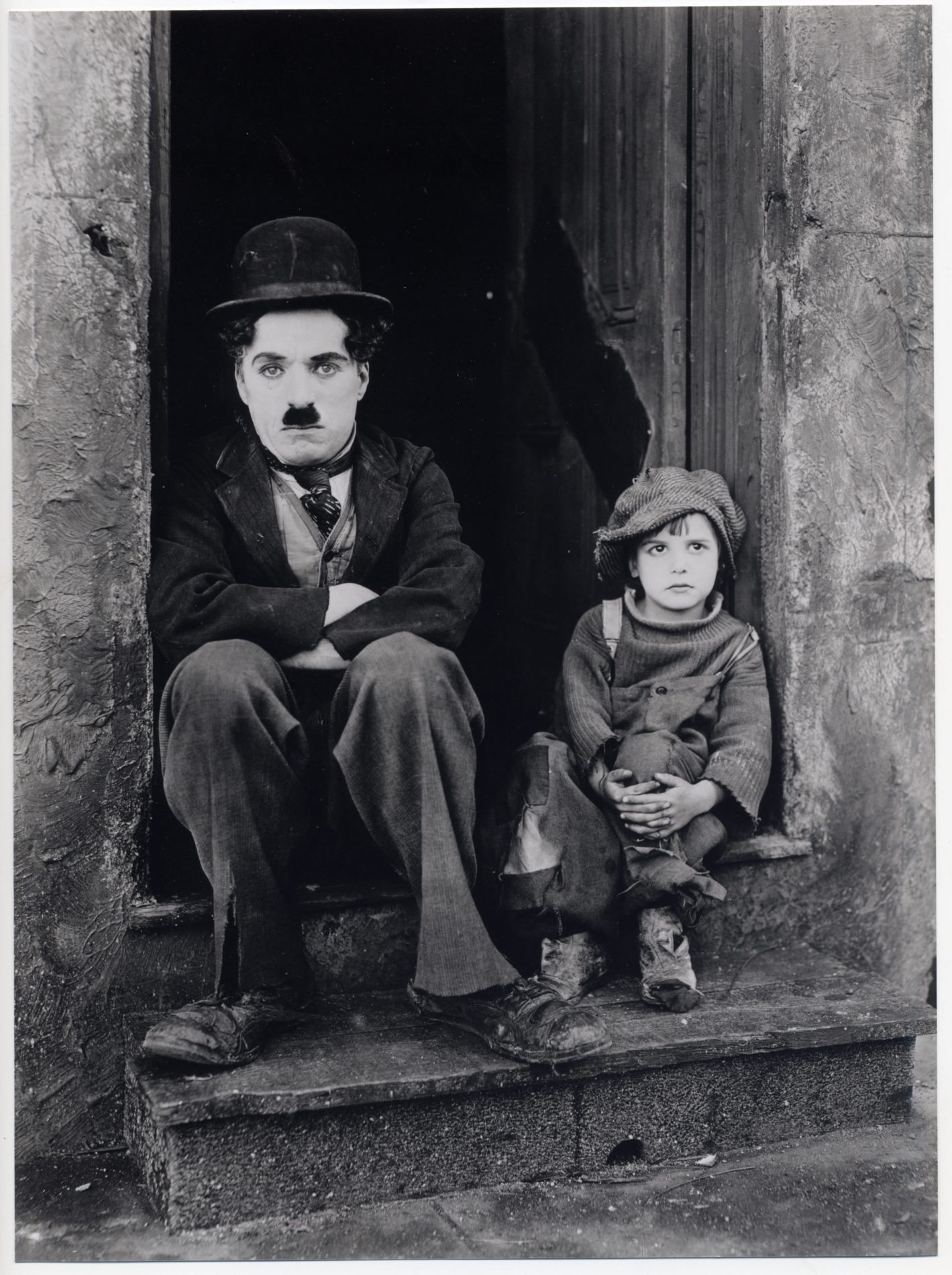

Since the cinema was considered a suitable tool for political goals, local governors gradually started to put it under their control. According to documents of the time, it can definitely be concluded that the cinematograph was primarily in the hands of the Royal family. It means that the people’s daily life, for example workers exiting a factory as famously filmed by the Lumière Brothers in 1895, was not the subject of any film. In other words, cinema had no involvements in social problems at all. Therefore, the atmosphere of the films made during the 1930s and 1940s was far from the bitter reality of Iranian society. Yet at that time, Charlie Chaplin movies, highly critical of society, were being made in the West.

As a result, Iranian cinema indirectly reflected establishment views and notions rather than revealing the pain and the crucial problems faced by society. This became worse when some severe restrictions were officially added to the laws regulating cinema activities after the 1953 Iranian coup d’état, a kind of coup d’état that prevented society from moving towards democracy. Moreover it influenced all media including print media, audio, visual media and even the emerging cinema. In fact, the power of cinema was first explored by the governors in Middle East countries, Iran included, and put in their service.

In the photo: Charlie Chaplin movies reflected the pain of everyday life but Iranian cinema never had this freedom.

The Modern Era 1950s -2000s

In the second part of the Twentieth Century, some Iranian filmmakers protested against current cinema policies and, in a spirit of reform, they brought new social and political ideas into their movies. Eventually, as a result of a political evolution, a rare miracle called the “Iranian New Wave” occurred. A new movement had arrived in Iranian cinema. It was a kind of realism that changed Iranian cinema. It expanded through various films, and grew far away from the fears of an earlier era that had acted as a damper.

The most impressive films made during the Iranian New Wave include: The Cow (1969) one of the first Iranian films that won awards at the Venice and Berlin film festivals; Qeysar (1969); Tranquility in the Presence of Others (1972); Prince Ehtejab (1974); Dead End (1977) and The Cycle (1978).

Unfortunately most of them were not allowed to be screened in Iran. Despite the rapid development of media and television popularity among people, the concept of the Freedom of the Press as one of the pillars of democracy had not yet come, due to censorship. At the end of the 1970s, a religious revolution took place and was followed by the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). Iranian cinema was strongly influenced by these events. As a result, the war genre officially entered in Iranian cinema for the first time.

The war films attempted to narrate the story of the Invasion of Saddam’s regime into the Iranian homeland. During the wartime period, making war documentary films with support from governmental funding became prevalent. This caused a distinct gap between filmmakers and divided them into two groups. The first group was funded by the government and tried to represent an ideological and religious cinema. The second group, since it didn’t receive any funding from the government, had a less ideological approach and attempted to address the realities inside the society. Unfortunately the challenge between these two conflicting groups still continues. The second group owes its life to the late modern era and the early postmodern era.

In the photo: Jets fly overhead. The Iran-Iraq War left a distinct impression on Iranian film. Photo credit: UX Gun

Moving to the Post Modern Era of Iranian Cinema with Jafar Panahi’s Taxi

Since the mid 2000’s, Iranian cinema gradually stepped into a new era of communication called the “postmodern era”. The cinema’s evolution was accelerated by (1) easier production procedures, and (2) faster, more direct distribution of movies. The era began with digitalization of movies and continued through the development of CD and DVD markets and internet release. Hence independent filmmakers in the Middle East including Iran, could overcome censorship and directly represent their short and feature films to their audiences.

Jafar Panahi is an iconic figure of the Iranian cinema. His style is known as an Iranian form of Neorealism. He first became well-known with “White Balloon”. Moreover, for the first time in the history of Iranian cinema, he defended the human rights of Iranian women: We see them banned from attending stadiums in his film the “Offside”. Most of his films were not allowed to be shown in Iran. He was arrested in the course of the presidential election in 2009 and banned from making films. However he kept on his professional work in secret with his incredible motivation for representing the social and political problems of his homeland. Considering his method of filmmaking, you will notice how cleverly he uses the technology to oppose censorship. The “White Balloon” was shot on the Original Camera Negative while a filming license was required for external shooting.

It is obvious for every cinematographer that shooting, as Panahi did, with a 35mm camera and total lack of budget or any supporting facility is very hard or even impossible. But several years later, Panahi did it again. He made “Taxi” in secret relying on modern technology thanks to the Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Camera. He won Berlin’s Golden Bear for this film but, because of travel restrictions, he was unable to attend and receive his prize. The “Three Faces” is another impressive film he made which attracted international attention after “Taxi”. In fact “Taxi” marked a new beginning for Jafar Panahi who it still making new films despite all the difficulties and restrictions blocking him.

Part of his secret in making his films in the years 1995 to 2015 is that he took advantage of the new technology in our postmodern era. However, his innate talent and creativity remains fundamental and is incredible. Although his films were banned in his homeland, they successfully grabbed international attention at different festivals in various countries. Thanks to the evolution of technology in our postmodern era there is no need to print films. Moreover it is not required to watch movies in a cinema. So independent filmmakers no longer need to get production and screening licenses from the government. They can directly distribute their films to their audience’s homes.

In the photo: Jafar Panahi could not use large cameras such as these- instead he used small hand-held digital cameras Photo credit: Hester Ras

Now in the post-modern era the cinema directly reflects public opinion rather than government attitudes: There is tremendous potential for winds of change to blow across Middle East societies.

Jafar Panahi’s Taxi is a yellow automobile like the other taxis in Tehran crossing the old back streets and highways carrying passengers all around the city. The passengers are usually from the middle class: A simple worker who had an accident and should be taken to a hospital; a superstitious woman insisting on putting a goldfish in an old small pool at a specific time; a little girl who must make a short film as a school assignment but she has to pick Islamic and holy names for good characters because her teacher said so. Another one is Nasrin Sotoudeh – a famous human rights lawyer- complaining about the suppression of free expression by the government and turning the country into a silent prison.

Jafar Panahi’s Taxi is a humble place for listening to people’s heartaches and the pains of society in a postmodern era. A Taxi heading towards freedom of speech. Now the question is “what if the governors get in this Taxi someday?”