I met Nicholas Goodly at The West End Lounge on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. The bar was nearly empty but we still found ourselves shouting to compete with the Soul music blaring from the sound system. The West End Lounge itself is a bit of an oddity, traversing a space between gay bar, neighborhood dive and performance space–posters for an Open Mic Night hang on the wall next to a promotion for a drag show called Haus of Mouth. The inclusive, multitudinous spirit of the bar seemed fitting when discussing Nicholas Goodly’s poem, “Black Mecca“. The poem is a multi-faceted, swirling portrayal of one of America’s most vibrant cities, and Georgia-native Goodly dexterously weaves each layer of the city into his love letter.

The title of this poem is “Black Mecca.” I know that Atlanta is sometimes described offhandedly as a Black Mecca. Was using this nomenclature and context a conscious decision on your part?

Nicholas Goodly: It was definitely a conscious decision. I was trying to express ideas of Blackness…and Atlanta is also known as a Queer Mecca of the South, so those were some phrases and ideas that I was working on within the title.

When I read the poem I thought that there were two main undercurrents that informed the verse: the first being a sense of Blackness, and the second being a sense of American Southernness. The distant third would be the shadow of Queerness that seems to haunt the poem.

N.G.: The poem is about a place that’s my home, and a place that I’ve developed relationships with—every part of my identity and every part of who I am as a person, so these things kind of come out when I’m talking about home. And anything that you form a relationship with, anything that you decide that you love, you have compromises and negotiations that have to happen, and that’s what I was trying to bring out in the poem.

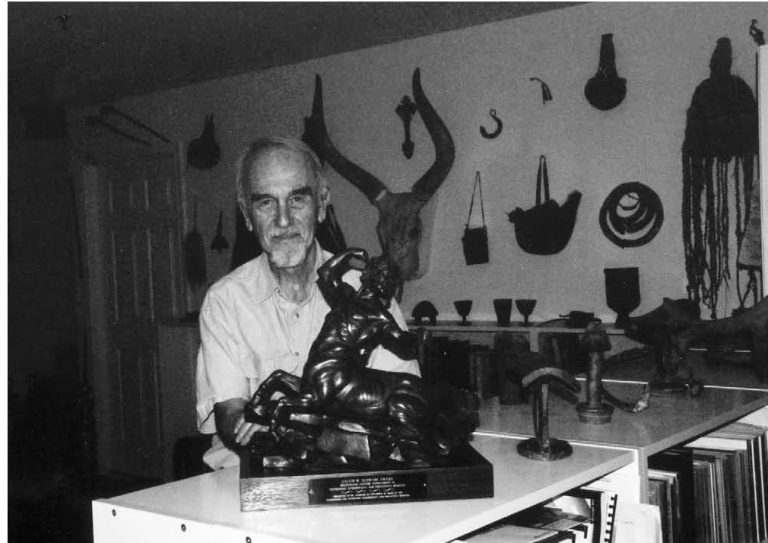

IN THIS PHOTO: NICHOLAS GOODLY, PHOTO CREDIT: JORDAN SOMMERLAD

So did these themes form organically or did you set out to write a poem that would speak to your identities?

N.G.: No, I think I just set out to write a poem about Atlanta, and of course it’s going to be personal because it’s so important to me.

Is it through the prism of you as a writer?

N.G.: Yes. It’s a very personal Atlanta. It’s not everyone’s Atlanta, or experiences. Anyone’s home is not anyone else’s home, so I feel like that’s why it seems so specific to me, and why things about myself as a person come up to the forefront so clearly.

Similarly, I thought that there were echoes of a certain Southern dialect. Not overt, but still present. Again, is that a conscious decision or is that something that just comes out by virtue of you talking about a place that’s so important to you?

N.G.: Typically, I try to create a voice that is true to my own person, and that means compromising my words as myself and choices as a writer, which of course can be two different things, but I’m trying to coalesce them in a way that I feel represents myself in both capacities. For this poem specifically, the Southernness may have come out more pronounced—my parents are from Louisiana, I’m from Atlanta. Those kinds of tones may have come out more when thinking about a poem of place and identity.

Related article: “ARTIST HABITS: CREATIVITY ON SMALL SPACES”

IN THIS PHOTO: NICHOLAS GOODLY LOOKS OUT OVER ATLANTA, PHOTO CREDIT: ALEX DUNCAN

And at the same time, though, there’s a subversion or complication of traditional southern tropes. Is that a conscious decision, or is that something that just happens as a product of your complicated personal relationship with the city?

N.G.: Well, that kind of playing on tropes and uses of phrases that I have, not only in this poem but in other poems that I have, is because I’m not trying to use logic…my first goal is not logical sense for a poem. It’s an emotional sense or an intuitive sense that I want…that I personally value more in my writing. So that’s why phrases may come off more twisted, or off, or nonsensical if you’re thinking about sense in the context of logic.

Your leaps are more associative and personal, and therefore less obvious in a logical strain. Can you talk about the form as this can be challenging at first glance?

N.G.: So, the form is a Crown, or it started off as a Crown. It’s not a traditional Crown anymore because Crowns are…it’s not a traditional Crown. A Crown is a series of sonnets where the last line of the first sonnet is the first line of the second sonnet and so on. So the fourteenth line is the fifteenth line, and the twenty-eighth line is the twenty-ninth line and so on. This is a short Crown of only three sonnets, and they’re not even traditional sonnets, they’re just feelings of sonnets. Which means I was going for five beats per line, but I allowed it to have a looser frame and just kind of take the gist of a sonnet, and let that live on its own.

At what point in the generative process did it become a Crown? Was it early or was that something that took form as you were writing it?

N.G.: I first decided I was going to write a Crown, and then I chose the subject of Atlanta because it’s something that I can look at from so many different perspectives and so many different windows and angles. There’s an insider window. There’s a “citizen of Atlanta” perspective. There’s an outsider perspective. There’s a historical perspective of Atlanta. There are so many ways you can look at a city and it moves through the poem. The first Crown is looking at the life of vitality that the people in Atlanta naturally carry about themselves, but also the power that that brings. Because they’re the music capital. They’re a hip-hop capital, and their energy is so contagious. The Atlanta energy is contagious, especially in the nightlife scene. The second one moves into a more personal reflection of Atlanta, looking at how sexy and hot Atlanta is. People are literally sweating all the time.

A corporeal nature?

N.G.: There’s such a sense of hot bodies existing and making connections. Being around each other in such a state is such a unique sensation to Atlanta. People are literally cooking, and we’re cooking together.

The idea that the city is cooking …

N.G.: Yes! The city is cooking and that’s hot. But the last stanza is about…I describe it as the porch-side-Atlanta. It’s the quiet Atlanta. Petals are falling in the street. Dogs are being walked. You’re sitting there with a cup of coffee or a cup of whiskey, just watching the day roll by because it still has the Southern slowness to it. And that’s the most intimate part. The part that only true Atlantans experience. And that’s a moment to end on.

For a full mindmap behind this article with articles, videos, and documents see #poetry

I know these different elements of Atlanta and the South are very important to you, in part because you are the writing editor of Wussy Magazine. Can you talk a little bit about what Wussy Magazine’s mission is?

N.G.: So, it’s an art and lifestyle online magazine for Southeastern Queer culture. One of the most positive things I experienced, being in Atlanta, especially in the artistic circles, was that there were so many hungry artists there that create their own spaces, that don’t hesitate to work together with a venue, put on a show of quality work, challenging work—whether we’re talking about dancers, drag queens, photographers, visual artists, writers—there’s such an uncompromising mentality for the artists that I encountered. That they wanted their voices heard—that they wanted to advance their own voices…such a fresh way of thinking that needed attention and needs to be seen.

This poem feels like a nuanced portrayal of Atlanta. This is not the Atlanta of a guidebook, but it’s maybe the reality for a young person living in Atlanta.

N.G.: It’s…it’s my experience. And with any poem you want to be able to find new meaning in experiences of others. So this is my take on Atlanta, and hopefully, I’m offering a new take in that way.

Absolutely! Just, again, looking at the content of the poem, there is also certain “witchiness” or “mysteriousness” about Atlanta that appears in this poem. How important is that to your Atlanta experience?

N.G.: That’s an element that creeps up in my work that is important to how I make art, first and foremost, and by element I mean “the occult,” and things that…

Is that a quintessentially Southern thing? Is it ingrained in Southern culture?

N.G.: It may be an element from the art community that I grew up, where that was a motif and idea that was important to a lot of people in the scene, and they presented themselves so beautifully that it drew me in. And so it’s probably something that will always be a backbeat to the rest of the things that I write.

Does your background in performance art and dance impact the way that you perform a poem? I don’t mean in the literal, spoken-word sense, but rather the way that the speaker of the poem performs an identity or identity politics?

N.G.: What’s really exciting about poetry and the balance I’m playing with more and more—and I’m not sure I can even be certain what I say today is the same thing I’ll believe tomorrow—but that a poem comes from a poet, but is not the poet, the same way a performing artist, as a dancer—it is my body. It is my artistic voice completely. But it’s still not healthy to conflate the speaker of the poem with the poet.

IN THIS PHOTO: WRITER AS DANCER, PHOTO CREDIT: CORRIAN ELLISOR

IN THIS PHOTO: WRITER AS DANCER, PHOTO CREDIT: CORRIAN ELLISOR

The idea that any form you create will inherently be a reflection of you because it comes from you, whether or not you’re performing as “Nicholas Goodly?”

N.G.: Yes, and the best performances are the ones that offer the most seamless transitions. So playing with that line is really something that I want. I want to feel as exhausted in a poem as I did on my most exhausting dances. And emotionally, and physically, and spiritually spent in a poem, which is an untouchable goal. But I think the fun is in trying to achieve that.

Recommended reading: “A POEM BY SARA JOY MÀRQUEZ “

—

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE BY IMPAKTER.COM COLUMNISTS ARE THEIR OWN, NOT THOSE OF IMPAKTER.COM.

Interview with Nicholas Goodly Instagram.com