Indigenous peoples are regularly erased from discussions in North America, be it during presidential debates, the design of school curriculum, or in entertainment. In instances where they are in fact mentioned, it is all too frequently on colonial terms, from offensive sports mascots to harmful stereotypes on the screen.

When it comes to devastating issues such as suicidal youth or violence against Indigenous women, Western media is always quick to resort to sensational, victim-blaming headlines, reducing individuals to the anonymity of statistics.

In the United States and Canada, violence against Indigenous women directly relates to historical victimization.

Related topics: Indigenous Peoples and the UN SDG–Australia: Empowering Indigenous Population –Indigenous Peoples: Key Trends Affect Development –Indigenous Peoples and their Rights–Youth is a Formula for Peace

Domination and oppression of Native peoples increased both economic deprivation and dependency through retracting tribal rights and sovereignty. Native women are the group the most at risk for domestic and/or sexual violence. They experience physical assault at rates far exceeding women of other ethnicities and locations.

It is also interesting to note that according to the U.S. Department of Justice, at least 70% of the violent victimizations experienced by American Indian women are committed by people of a different race— a substantially higher rate of interracial violence than experienced by White, Asian, or Black victims. In Canada, the term Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) has come to encompass thousands of cases of violent deaths and suspicious disappearances.

Current government initiatives, especially in what is now Canada, recently relaunched the crucial dialogue between settler populations, new immigrants, and the original inhabitants of the land. From official apologies delivered by the Prime Minister and church leaders to federal and provincial funding for educational and artistic programs, the word reconciliation is everywhere

In the United States, recent victories in the courts put Indigenous groups in the spotlight. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) recently banned the use of Native American mascots. School teams such as the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s and Southeastern Oklahoma State University will have to change their logos and uniforms in order to participate in future tournaments.

Democratic candidate for 2020 Julián Castro recently unveiled a People First Indigenous Communities platform. With this plan, he promises to address difficulties affecting Native communities regarding the funding of education, access to health care, and discriminatory voting policies. Such an initiative has essentially been unheard of in the context of American presidential elections, especially considering his plan to better support tribal sovereignty and assist Native communities in dealing with harmful federal policies.

It is crucial to educate the public on these issues, and so too is focusing on strategies to better these situations.

In this article, I present ten Indigenous-led organizations and the entrepreneurs who created and are running them. I encourage settler-readers to go beyond reading about colonial violence and reach out to these initiatives. Stay informed on the treaties and land agreements that were signed with the Indigenous nations in your area. Learn how you can help. Ask what you can bring to these campaigns. Become an active ally and start participating in reconciliation.

Organizations such as Walking with Our Sisters have been instrumental in developing public awareness on the systemic violence against Indigenous women in Canada. They bring victims’ and families’ stories to the front of the stage as opposed to the political and law enforcement discourse in the media too often reduces people to numbers.

The group’s massive commemorative art installation traveled to over 25 locations throughout North America since 2013 and has attracted thousands of visitors. The exhibit is comprised of around 2000 donated pairs of moccasin vamps (the beaded top piece).

Entirely fueled by volunteers, Walking With Our Sisters is a collective working to create one unified voice to honor Indigenous women and their families.

Walking With Our Sisters is one of many collectives of Indigenous activists finding avenues for community healing and social change in art. Anishinaabe/Potawatomi artist Nancy King, from Mnjikaning Rama First Nation, uses the name Ogimaakwebnes or Chief Lady Bird to sign her art. It was given to her in ceremony by her grandfather Ralph King Sr.

In a September 2016 interview, King told MUSKRAT Magazine that her Anishinaabe culture and language are at the root of her practice: “Everything I have learned has been through observation, blood memory and through living in a house with parents that value culture.” She credits her father for taking her on medicine walks in the bush as well as her grandmother’s quillwork as foundational sources of inspiration for her art and for her personal resilience as an Indigenous woman.

On top of her work as a freelance artist, she works with at-risk youth at the Native Learning Centre in Toronto. Her goals are to “uplift, empower and educate” Indigenous children through the arts, and help them reclaim their cultures and discover their resilience.

With Monique Aura, Chief Lady Bird also facilitates OurStoriesOurTruths a Toronto-based visual storytelling project which focuses on art as a healing practice. Guest artists share artistic practices and Indigenous teachings with urban Indigenous youth.

Past workshops have included Maria Montejo, who introduced children to Mayan calendar teachings, Brian Charles who shared wampum teachings, and Alyssa Gagnon who taught moose hair tufting.

Chief Lady Bird also illustrated Nibi’s Water Song, the upcoming children’s book by Sunshine Quem Tenasco.

Sunshine Quem Tenasco is Anishinaabe from Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg. Her community has gone without clean water for 15 years. Committed to bringing awareness to this issue, she founded HerBraids. This online store sells beaded pendants and donates profits to the David Suzuki Foundation’s Blue Dot Movement, a national grassroots campaign advocating for the right to a healthy environment, including clean air and water for everybody in Canada.

Purchases from Tenasco’s stores raise funds, but in wearing the recognizable HerBraids pendants, consumers become activists and display their commitment. Tenasco also encourages supporters to share their resistance on social media, stay informed, and organize rallies and fundraisers.

In the past few years, raising awareness about climate change has been on the agenda for hundreds of activist organizations. Indigenous women-led collectives such as Seeding Sovereignty and Native Women’s Wilderness work to “shift social and environmental paradigms by dismantling colonial institutions and replacing them with Indigenous practices created in synchronicity with the land.” They work on behalf of the global community to raise the voices of Indigenous women and encourage educating Natives and non-Natives alike on ways to preserve the land we now all live on.

These organizations, committed to addressing climate change and energy justice were inspired by strong female leaders such as Winona LaDuke, a White Earth Anishinaabe environmentalist and economist who has been relentlessly working to spread awareness and support for environmental issues.

LaDuke’s organization, Honor the Earth, has developed financial and political resources to create and maintain sustainable Indigenous communities by using music, arts, the media, and Indigenous knowledge since 1993. Honor the Earth has sided with dozens of Native communities working to protect their sacred sites from being disrupted or, worse, destroyed, by intrusive developments.

LaDuke also created the White Earth Land Recovery Project (WELRP) in her home community. As a member of the Upper Midwest Indigenous Seed Keepers Network, they manage a library of rare Indigenous seeds. They collect the stories which accompany each variety, documenting the rich history of ancestral Indigenous agriculture in the area. WELRP also works to restore and maintain food sovereignty and participates in several farm-to-table programs.

Sustainability not only concerns resources and energy but also includes cultural sustainability. Too many Indigenous youths lack positive representations, culturally responsive education, and stability in mental and physical health. Indigenous women such as Johnnie Jae work to ensure an accurate representation of Indigenous peoples in American popular culture.

Johnnie Jae is an Otoe-Missouria and Choctaw journalist. She is a founding board member of Not Your Mascots, an organization dedicated to fighting against stereotypical Native representations in sports, and of Live Indigenous, an advocacy group which promotes accurate education and cultural sustainability.

Jae is also the founder of A Tribe Called Geek, a media platform for Indigenous geek culture and STEM. She runs this network of innovative Indigenous youth with colleagues Jack Malstrom, podcaster and DJ, and contributing writers Louis Fowler, Daryl Begaye, and Kayla Shaggy.

The platform works to promote the visibility of Indigenous contributions to pop culture and STEM. On their website, Johnnie explains: [that Indigenous youth]

“are just as invested in fandoms as the next person. I wanted to create a space where we could support each other and geek out together, while also flipping the script on the narrative that we were strictly primitive peoples. We have always been innovators, scientists, creators, and disruptors”.

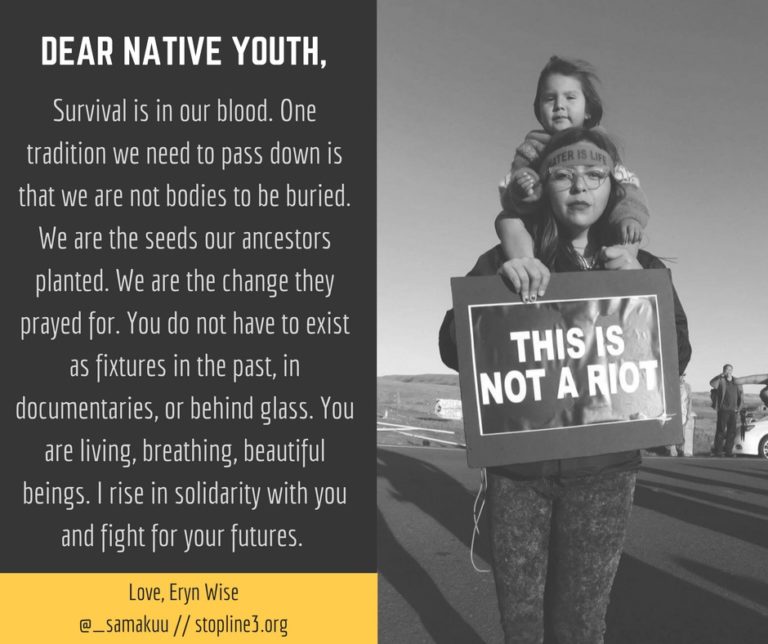

Environmental activism and the promotion of Indigenous talent helps Indigenous youth who might have lost hope in their future. For instance, Johnnie Jae is also a member of Women Warriors Work, a collective of Indigenous women in various professional spheres. Their campaign Dear Native Youth focuses on uplifting Indigenous youth. Through writing letters, Indigenous women members shared their knowledge, experience, and advice with teenagers, showing them how valuable their generation is.

Through her platform A Tribe Called Geek, Johnnie also created Indigenerds4Hope, a suicide prevention initiative that supports Indigenous youth struggling with mental illness.

Harmful stereotyping and the lack of educational and professional opportunities are only some of the multiple issues faced by Indigenous youth today in North America. Some genocidal practices committed by the colonial states, such as land theft, epidemics, or Indian Residential schools (Indian boarding schools in the U.S.), are perceived to be known but generally misunderstood.

Neither the Canadian nor the American public receive detailed history lessons on the intergenerational trauma that these policies inflict on Native communities today. Because people were beaten or imprisoned for speaking their language or practicing their ceremonies, hundreds of Indigenous and customs languages are now extinct.

Adding to forced relocations and boarding schools, colonial legislation such as the Indian Act and the excessive apprehension of Indigenous children by state family agencies tore apart families and severed instrumental community relationships, preventing transmission of knowledge between generations.

Suicide is an unmitigated crisis all across communities. In Canada, studies show that Indigenous youth suffer the highest suicide rate of any culturally distinct population in the world. Statistics Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, and the Canadian Center for Suicide Prevention pointed out that suicide and self-inflicted injuries are the leading causes of death for First Nations youth and young adults. The suicide rate for First Nations youth between 15 and 24 years old is approximately 5 times higher than for non-Indigenous male youth and 7 times higher for females.

In the United States, legislation such as the 2017 Native American Suicide Prevention Act, introduced by Democratic Representative Raul M. Grijalva, requires state organizations to collaborate with tribal and urban Indian organizations when developing youth suicide prevention strategies.

Editor’s Pick:

“Indigenous Peoples and the UN Sustainable Development Goals”

“How Pacific Feminists are Challenging United Nations Leadership Roles”

Programs for Native youth such as the Native Youth Educational Services Workgroup are funded by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services as part of the Indian Alcohol and Substance Abuse Interdepartmental Coordinating Committee. They also fund To Live To See the Great Day That Dawns, a suicide prevention program for American Indian and Alaska Native youth. The Canadian government introduced similar programs, including the National Aboriginal Youth Suicide Prevention Strategy (NAYSPS), a framework working to increase awareness and develop community plans for preventing suicide in First Nations and Inuit communities.

In both countries, cooperation among federal, state/provincial, tribal, and community partners ensures the efficacy of prevention programs. In most states, there is no specific taskforce dedicated to Native youth. They are amalgamated with the rest of the population in general prevention programs. Suicide prevention initiatives are most successful when they combine elements that promote resilience, participation in cultural spirituality, and community engagement.

We R Native is an online platform by the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board. They cover diverse topics such as physical and sexual health, culture, identity, and the environment. Teenagers who do not have the opportunity to communicate with an elder in their community can use the resource “Ask Auntie.” This online chat allows them to ask the questions they would ask an Indigenous mentor. Amanda, a 36-year-old Zuni Pueblo woman from New Mexico, provides answers weekly. We R Native also gives advice related to mental health.

We Matter is another Indigenous-led collective dedicated to helping youth deal with mental illness, substance addiction, and suicidal thoughts. Siblings Kelvin and Tunchai Redvers started the We Matter Campaign in 2016. They invited hundreds of Indigenous role models to create and share multimedia messages about their experiences of overcoming hardships. Non-Native allies also contributed pieces to help Indigenous youth find the strength to reach out for help.

We are at a time when climate change and political extremism threatens the safety of communities. It is crucial for settler citizens and new immigrants to learn about the first inhabitants of the land we now share, but it is not enough.

In order to better the economic, political, and social situations of Native communities in North America, we, as settlers, owe it to them to participate in the initiatives they lead on their own terms. We need to ask how we can contribute to dismantling the colonial structures which enable violence and discrimination to continue.

Indigenous-led organizations are setting an example, and we need to follow them.

Cover Photo Credit: Marc-André Cossette/CBC.