The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, an ambitious set of seventeen global goals and 169 targets to progress toward a sustainable future, has been heralded as more inclusive and comprehensive than the Millennium Development Goals before it, in part for its inclusion of Goal 16 on peace, justice and strong institutions, reflecting the inputs of countries who have struggled with domestic conflict and external intervention. However, implementation of the goal brings the risk of “securitizing” development, if done in a manner that prioritizes the security agendas of strong states, or impinging on state sovereignty. The United Nations Charter outlined the conditions of sovereignty which reinforce members’ identities as states operating within a cooperative framework, and define the parameters within which expectations are set regarding organizational goals such as the maintenance of peace and security in the world.

The United Nations has, since its establishment at the close of WWII, both legitimated and reified the principle of sovereignty among its members as it has introduced new concepts, policies and structures to remain relevant and address the realities of contemporary conflict. Its enduring reliance on sovereignty as a construct, though necessary, has created dilemmas for the United Nations while also providing clarity in this endeavor.

In early “first generation” peacekeeping missions, the UN typically played a role as mediator to a conflict, or observer of a peace agreement or process, as an invited participant. Although action taken by the Security Council had been severely curtailed by the use of vetoes during the Cold War, in the post-Cold War period states turned toward the United Nations for security assistance as the level and intensity of intrastate conflict subsumed that of conflict between states.

In this new generation of conflicts, where the legitimacy of state actors is often called into question, both taking any decisive action, or refusing to do so may be interpreted as a breach of impartiality by international organizations seeking to remain neutral. Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali confronted the tension between sovereignty and security in his 1992 report “An Agenda for Peace” when he stated:

The time of absolute and exclusive sovereignty, however, has passed: its theory was never matched by reality. It is the task of leaders of States today to understand this and to find a balance between the needs of good internal governance and the requirements of an ever more interdependent world.

In the Photo: General Assembly Opens Seventy-first General Debate Photo Credit: UN Photo/Cia Pak

The tone taken in the Agenda for Peace report is aspirational, considering the opportunity for interstate cooperation in the post-Cold War era. In it, Boutros-Ghali introduced the new concept of “post-conflict peacebuilding” that highlighted the longer-term needs for engagement and complex nature of post-conflict situations at the time. The Agenda’s 1995 supplement presents an analysis tempered by the lessons learned in the by then failed interventions in Somalia.

Technical issues related to coordination and the command and control of troops in the Somalia peacekeeping operations stymied effective deployment. Moreover, many peacebuilding-related activities resulted in a bloated and unclear mandate as responsibility transferred between the US-led humanitarian mission Operation Restore Hope and United Nations UNSOM missions. When US Domestic support for intervention, closely monitored by President Clinton’s administration, sharply declined ahead of the 1994 midterm elections, the time had come to “bring our troops home from Somalia.” Mohamed Sahnoun, Special Representative to the Secretary General in Somalia, left his post citing the UN’s many “failed opportunities” in building trust through negotiation and communication, which he argued required more time than was allotted by the mission.

The Somalia shadow was cast over Rwanda when crisis struck there soon afterward and troop contributing countries declined to put forward peacekeepers. As noted in the 1995 Supplement to Agenda for Peace, the complexity, extending to national reconciliation efforts and reestablishment of effective government in some cases, as well as the additional expense of peacekeeping in volatile settings, can deter intervention.

The concepts of human security and human development stem from these and other experiences (with human development introduced in the UNDP Human Development Report in 1994), and seek to connect the individual with a universal, rights-based agenda whose enforcement must ultimately be guaranteed by states.

The UN began making structural modifications to its bureaucracy to facilitate the implementation of concepts as they were being developed. A Peacebuilding Architecture was established, consisting of a fund for states to voluntarily contribute to peacebuilding and statebuilding efforts. A Peacebuilding Commission was established to “provide recommendations and information to improve the coordination of all relevant actors within and outside the United Nations,” supported by a New York-based Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO).

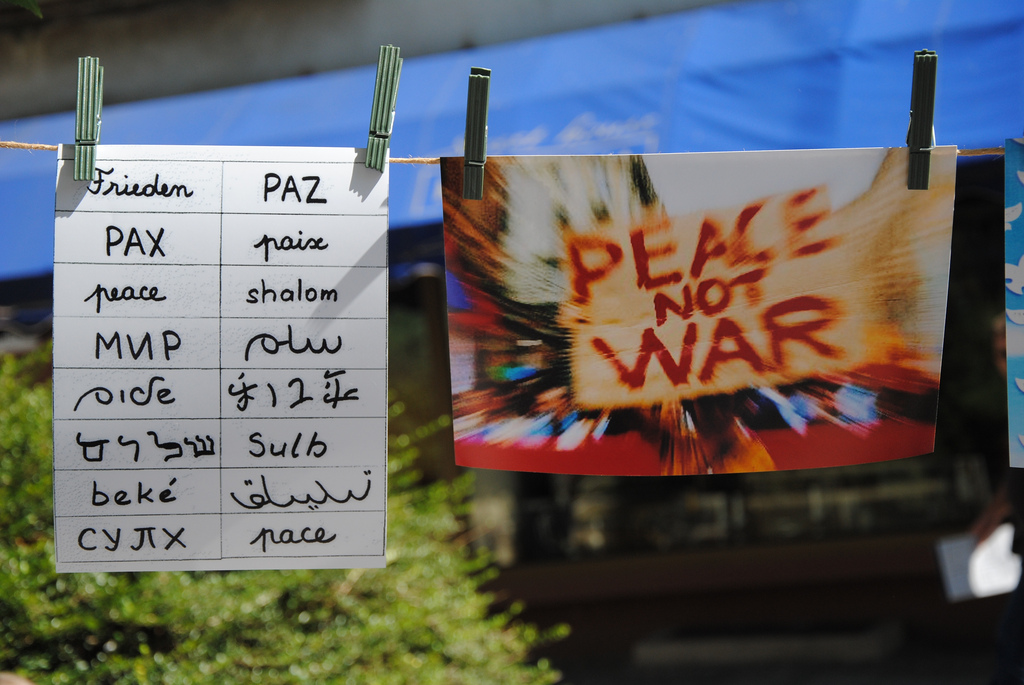

In the Photo: Peace Day in Serbia, 2010. Photo Credit: UNDP/UN Serbia

As these structures were being built to aid in mitigating and addressing conflict and post-conflict situations, the Canadian government sponsored an effort to advance a normative framework to guide states’ response when internal conflict is imminent. In 2000, the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty was established to confront the tension between sovereignty and security. Co-chaired by Gareth Evans and Mohamed Sahnoun, the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) purported to respond to an emergent “culture of national and international accountability” present in the shift toward a human rights approach in international relations.

Related article: “SDG 16: PLATFORM FOR A NEW ERA OF INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION”

While the state whose people are directly affected has the default responsibility to protect, a residual responsibility also lies with the broader community of states. This fallback responsibility is activated when a particular state is clearly either unwilling or unable to fulfill its responsibility to protect or is itself the actual perpetrator of crimes or atrocities; or where people living outside a particular state are directly threatened by actions taking place there.

In 2005, at the UN World Summit, countries adopted the basic tenets of the policy.

Yet, the notion of bearing a responsibility to protect populations in other states through military engagement has had a mixed history of implementation as a norm. The 2005 World Summit document makes no reference to the responsibility to rebuild, considered in the 2001 ICISS report as a third element following the responsibilities to prevent and to react.

In Libya, the invocation of the Responsibility to Protect has been rebuked either as a façade for regime change, allowed to proceed by the abstention of Russia and China in the Security Council, or for its reliance on intervention while neglecting measures for prevention and rebuilding. During the Libyan intervention, despite the potential clarifying aspects of R2P, its implementation resulted in mission creep, in contravention of its operational principles to maintain clear objectives and an unambiguous mandate, including prioritizing protection of the population over defeating the state.

Photo Credit: Flickr/watchsmart

In Syria, both the international and domestic aspects of sovereignty addressed under the R2P framework, of territorial control and the effective protection of citizens, is non-existent, and a proto-territorial state ruled through terror and coercion is embedded among its fragments. The international community weakly called upon Assad to uphold his responsibility to protect Syrians when conflict erupted in 2011. As Russia and China repeatedly blocked efforts by the Security Council to secure a humanitarian response, atrocities committed by the Assad regime increased, emboldened in the face of inaction. The Obama administration declined to take decisive action when Assad used chemical weapons against civilians, preferring instead to conduct airstrikes and provide limited support to rebels.

Speculation has turned toward how the Syrian state will emerge and recover from its grave losses in years to come, amid extreme factionalism, destruction, and the hemorrhaging of its population to death and displacement.

A recent review of the Peacebuilding Architecture (2015) reflecting the latest thinking on how to operationalize peacebuilding, calls for “inclusive national ownership” (defined as broadly shared effort across groups, divides, and social strata) of peacebuilding activities, to guard against the rationalization of inaction by the international community in cases where “national ownership” is limited to elites. The current sustainable development agenda, while not mentioning military intervention, does contain guidance and expectations for addressing conflict-affected or fragile contexts that could impinge on state sovereignty, or pose a risk of securitization.

In the Photo: The Peace Palace, seat of the International Court of Justice, at The Hague, Netherlands. Photo Credit: UN Photo/ICJ/Jeroen Bouman

The content of Goal 16, to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions,” offers specific targets, such as target 16.a, calling for the strengthening of “relevant national institutions, including through international cooperation, for building capacity at all levels, in particular in developing countries, to prevent violence and combat terrorism and crime.” This language marks an evolution in thinking from the 1995 Agenda for Peace supplement which noted the UN’s reluctance to “assume responsibility for maintaining law and order” and stated, “nor can it impose a new political structure or new state institutions.”

In advance of deliberations that fed into the SDG process, representatives from seven countries considered to be “fragile” by intergovernmental organizations, the United States and Europe (a categorization that tends to include countries impacted by the long-term effects of domestic conflict) came together to assert that they, specifically, do possess the will to exit and remain free from conflict to pursue sustainable development, but require peacebuilding and statebuilding assistance for a period of time. Developed in consultation with representatives of such states, Goal 16 incorporates some of the demands of this group (formalized as the G7+) on their development partners, namely those states who are best positioned to provide intervention either through aid or the military.

Ultimately, implementation of Goal 16 will depend on the political will of powerful countries like the United States, which, under President Trump, is currently poised to take an increasingly isolationist posture toward the United Nations, while bolstering the military. As Syria and other states currently experiencing conflict eventually move toward peacebuilding and statebuilding, making effective progress toward Goal 16 is likely to be determined as much by politics and power as international norms.

Recommended reading: “SDG 16: PEACE JUSTICE, AND STRONG INSTITUTIONS”