The Graduation Approach Is Helping Refugees and Displaced People Become Self-reliant so They Are no Longer Dependent on Aid

Today, the world is facing a global migration crisis. The number of forcibly displaced people around the world is greater than the current population of the United Kingdom, having reached a record high of 68.5 million people. Of those displaced, 25.4 million are refugees, and their reasons for leaving their homes vary. Families flee due to persecution, violence, human rights violations, or climate change, and their process of displacement affects what label is assigned to them: refugees, asylum-seekers, returnees, internally displaced persons, stateless persons.

Marie* and her family are refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Since 1993, they have lived in Meheba, a settlement in the northwestern province of Zambia, 430 km from the capital Lusaka and 41 km from the border of DRC.

Typically, photos of refugees, or displaced people in general, display a camp setting: tents and make-shift homes organized in over-crowded blocks mask the terrain, and people lay idly around. In these camps, refugees are usually reliant on food assistance programs and other types of support from international relief organizations such as UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, or World Food Programme. While Meheba looks nothing like that — single room houses built with sand stone blocks are spread across the bush — the cycles of dependence are no different and far from sustainable.

When they first arrived at the settlement, Marie’s family received a variety of aid for a year and half: food items, agricultural tools, three hectares of land, a water hose, and a tent. With what little they had, her family then built their own home from sand blocks traditionally collected from anthills. Afterwards, they struggled to make ends meet from the odd jobs they took, the fritters they occasionally sold, and the few plants they grew — like many Congolese refugees, Marie’s family had never farmed before. On the toughest days, they could not afford to eat even one meal a day. Marie, like the other 22,2089 refugees in the northwestern province, deserves better.

That’s why Trickle Up, a global poverty alleviation nonprofit, has been working with UNHCR and its local implementing partners to help them provide an economic development approach called Graduation in ten operations around the world, including Zambia. Developed over the past decade to address the unique needs of vulnerable people living in extreme poverty, the Graduation Approach has since been proven effective in humanitarian contexts, making it a powerful tool to help us achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

The Graduation Approach is community-centered and bottoms-up. Aiming, in a humanitarian context, to address the long-term dependence of displaced populations on aid, it presents an innovative approach to ending poverty in all its forms everywhere, the UN’s number one sustainable development goal (SDG 1), with a specific focus on target 1.5:

“By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations, and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social, and environmental shocks and disasters.”

With its unique, sequential, and time-bound components, the Graduation Approach overcomes many of the challenges faced by the current humanitarian system. Working with a coach who guides and tracks individual progress, families develop income-generating activities particular to their current environment. To help participants succeed, they sometimes receive a stipend to cover basic, immediate needs for a limited time. In some contexts, refugees are already receiving this stipend from the World Food Programme, for example. No longer forced to worry about where they will get their next meal or how they’ll pay for medical care, families can focus on long-term planning and growth. Once earning a steady income, they begin to save for the future. All along the way, coaches provide encouragement and support.

“I wasn’t a business woman. Now I’m a confident market woman,” Marie affirms at the market inside Meheba. Thanks to the business training Marie has received, she now sells dried fish here. On Monday mornings, she arrives early to meet the local supplier and purchase the best quality products. When she has enough money, she buys a goat as collateral that she can quickly sell when needed.

The comprehensive design of Graduation is key to building refugees’ resilience against shocks and independence from aid, especially as the amount of humanitarian funding continues to pale in comparison to the growing global need. In its 2019 Global Appeal, UNHCR asked for almost $8 billion of funding to address the crisis.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

“A New Response to Refugee Inclusion”

“A Life Dedicated to Refugees: Interview with Kelly Clements”

In many situations, the reality of displacement is long-term. On average, refugees spend 26 years in displacement. Some refugees make it to their 20s, having known no life other than that inside their camp or settlement. In other words, these cycles of dependence are not simply day-to-day, rather year-to-year, and even intergenerational. While Marie recalls her life in the DRC, her youngest children have only known life in Zambia. Situations of displacement lasting more than five years are called protracted, and displaced populations imminently need long-term solutions that build independence from aid that could disappear one day. As situations last longer, media coverage decreases, and donor fatigue prevails. The money goes to the next more immediately urgent situation.

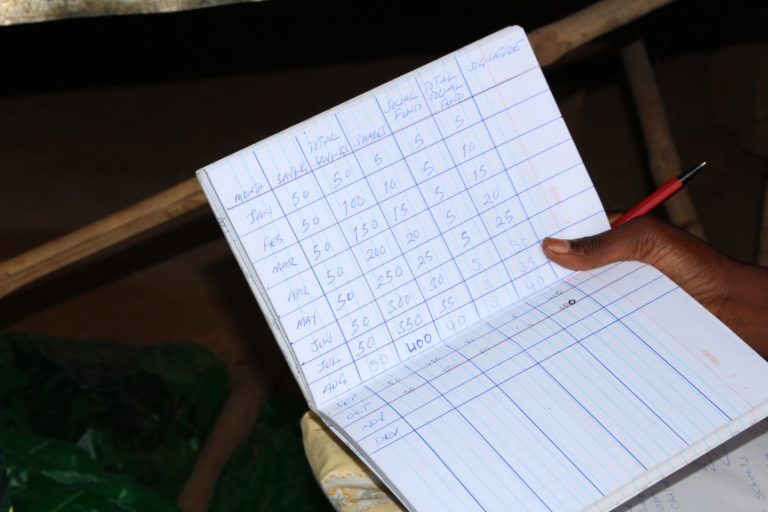

Even before Marie started generating an income, she was saving money with a group of other refugees who are participating in Graduation as well. These savings can be used to expand her business, support her family, and cover her expenses in the case of a few bad days at the market.

Beyond the increased financial access and literacy, these savings groups also provide an avenue for Graduation participants to expand and build on their social networks. As heads of household meet other individuals whose families are facing similar situations, the hopelessness around loneliness fades.

While many refugees live in rural refugee camps, that is not always true. In many countries, refugees have no right to work or even own land and must seek opportunities in the informal economy. Word often spreads of potential economic opportunities in urban areas, and the informal labor markets of cities, which may allow for more creative income-generating activities, become an attraction. But these activities can be dangerous and include sex work, street-side vending, and under-the-table jobs with physical hazards. As they move to urban areas, some refugees choose not to register with UNHCR or an appropriate relief organization, leaving them without documentation critical to accessing benefits and avoiding arrest. In Zambia, if refugees are caught by authorities in the capital city of Lusaka without the proper identification, they are swiftly sent back to the settlement or arrested. Since urban neighborhoods are often more crowded and spread out, refugees become harder to identify and fall through the cracks of the system, missing out on key opportunities to receive various kinds of support.

Despite the rumors of opportunity in urban areas, life does not necessarily get easier for affected populations who have moved to the city or its outskirts. As families deplete whatever assets they managed to bring with them, the need for income pushes them to unconventional means. This puts family members at risk, exposing them to potential exploitation and harassment, often compounded by discrimination in the host community.

Eighty-five percent of the world’s refugees are received by host communities in developing countries where existing scarcity and an influx of distressed arrivals can inflame social tensions. Host community members tend to blame newcomers for perceived rises in national unemployment, for example, even if unemployment was high before the sudden arrival of labor. To combat xenophobia and build relationships between host and refugee communities (and among refugees of various identity groups themselves), Trickle Up always works with both displaced and local populations when designing and implementing Graduation programs in host communities.

By bridging the gap between seemingly disparate groups of people at such a micro-level, the Graduation Approach builds understanding, empathy, and compassion. Including the host community in all Graduation components is integral to ensure program sustainability and increase impact. Even beyond their savings group, the sense of solidarity expands to a participant’s daily life. “When you have nothing and are feeling hopeless, you feel gratitude for anything a neighbor gives you,” Marie explains, as she describes her newfound friendship with a neighbor of different nationality in her block.

Whether in a rural, urban, or settlement setting, families in displacement are less likely to report injustices to the authorities. Being unaware of their rights, fearing persecution, or worse, deportation, and lacking any kind of support system, vulnerable families find themselves alone in this unwelcoming new world. As a result, Graduation prioritizes awareness around social protection and access to basic services early on in the program. Through clearly communicating all available services as well as displaced peoples’ rights and responsibilities from the onset and in refresher trainings, individuals build their own core capacity to take their future in their own hands.

Adapting Graduation to displaced populations is a nascent phenomenon, so learning has been central to each one of these projects. By always starting with a small pilot and having a well-defined research and learning agenda, Trickle Up builds out smart and effective scale ups. Every iteration of Graduation for displaced populations leads to a more refined, holistic, and effective approach helping reach more people around the world. In 2013, Trickle Up started adapting Graduation for affected populations in coordination with UNCHR, in pilots in Egypt, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Zambia, and Burkina Faso. Today, five years later, Graduation has been implemented in 12 countries on three continents, in collaboration with local governments, UNHCR, and other NGO partners, thanks to a generous multi-million dollar grant from the US Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration.

In December 2018, United Nations member states agreed to a Global Compact on Refugees, which aims to expand effective programming that enhances refugee self-reliance, measure refugees’ progress to build the evidence base, and advocate for funding and hosting environments that promote self-reliance. This compact and Trickle Up’s current and future work go hand in hand. By championing this compact and making it a reality through Graduation, Trickle Up, their allies, and women like Marie are restoring hope for those who are displaced and host communities alike. It is the only way to achieve SDG 1.5 for everyone, everywhere.

“I am a changed one,” concludes Marie, as she starts tidying up her stand in the market. Her face shifts from a soft smile to a focused gaze, and now more than ever, she understands that time is money.

Editors Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — Featured Photo Credit: Ross Savchyn

*All names changed to protect refugees’ confidentiality.