Across the world, we all face the same health workforce issue: The pool of health professionals is insufficient to meet the needs of the people, whether they live in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) or developed countries. The global health workforce crisis is putting at risk one of the key UN Sustainable Development goals, SDG3. This is because health workers are key, they are the “gatekeepers” to achieving global health. Unless serious corrective measures are taken, we may not be able to achieve universal health coverage by 2030.

Health matters and an effective health workforce can operate miracles, as the polio vaccination campaign in Pakistan strikingly illustrates. Here, for many years, health workers bravely risked their lives and many unfortunately died in the race for polio vaccination. Eventually, thanks to their unfailing dedication, the situation finally came under control:

The challenge begins with professional schools. In the past in LMICs such institutions were often public institutions reliant on public sector budgets, providing low tuition costs to students. Often the health establishment was reluctant to allow the development of private training institutions to complement the public ones hit by the flatlining of public sector budgets.

The rhetoric at highest levels acknowledged that what was wanted and needed was quality education and producing sufficient numbers of fit-for-purpose graduates. Without new resources and an opening to innovative teaching approaches, the possibility of achieving both quality education and quantitative goals appear insurmountable.

In some instances, the public sector institutions are reportedly very successful in doing so, but in most other cases school leadership and professors do not have the management and technical skills to perform their assigned functions. Everyone remains looking in the rear view mirror in the hopes that the past will return.

As a result, many graduates are not well suited for real life practice environments; there is a mismatch between employer needs and health worker competencies; and those who are the best and brightest are drawn elsewhere.

The healthcare services market is a global industry, much larger than many, and far less regulated than most. It is an odd industry in that skilled workers are produced in great numbers in some poorer countries, such as the Philippines, to fill the gaps in the OECD health pyramid.

In contrast to what happens in healthcare services, many other markets, such as agricultural products or extractive materials, use LMIC low or semi-skilled workers to provide the inputs to add value to what they produce and then export as finished goods. Here, the most skilled health workers migrate, drawn by market forces to better opportunities.

Wealthier countries need more doctors, nurses, laboratory technicians and pharmacists, and can offer higher salaries and better living conditions than those in the country where the health workers were educated. Over the past decade, according to WHO data, there has been a 60% rise in the number of migrant doctors and nurses working in OECD countries.

This results in health worker shortages in LMICs, making it difficult for health facilities to recruit and retain the staff they need to provide a broad array of quality services to the local population.

Take the Philippines as an example. It adopted the “Philippine HRH Master Plan (2005-2030)”. This country annually produces tens of thousands of health care professionals, medical technicians and pharmacists. But it only has roughly 3.5 health professionals for every 10,000 population, well below the WHO desired ratio. In 2014 at a Philippine conference it was argued that the Philippines has become “a solution to other countries’ shortages”, as many Filipino nurses and doctors migrate to other countries for higher-paying jobs.

There is also a “maldistribution” of health workers in the country, with most physicians wanting to stay in urbanized areas. This is because most development efforts are in the cities “where the money is.”

In spite of the Master Plan and the support it has elicited from donors like USAID, the situation is still critical.

Less important in terms of numbers, but nonetheless remarkable, health workers also migrate from one LMIC country to another when they find better working opportunities there than are available at home; for example, they go from India to Uganda or from Uganda to Kenya and Botswana, Namibia, Zambia:

The United Nations’ Response to the Global Health Workforce Crisis

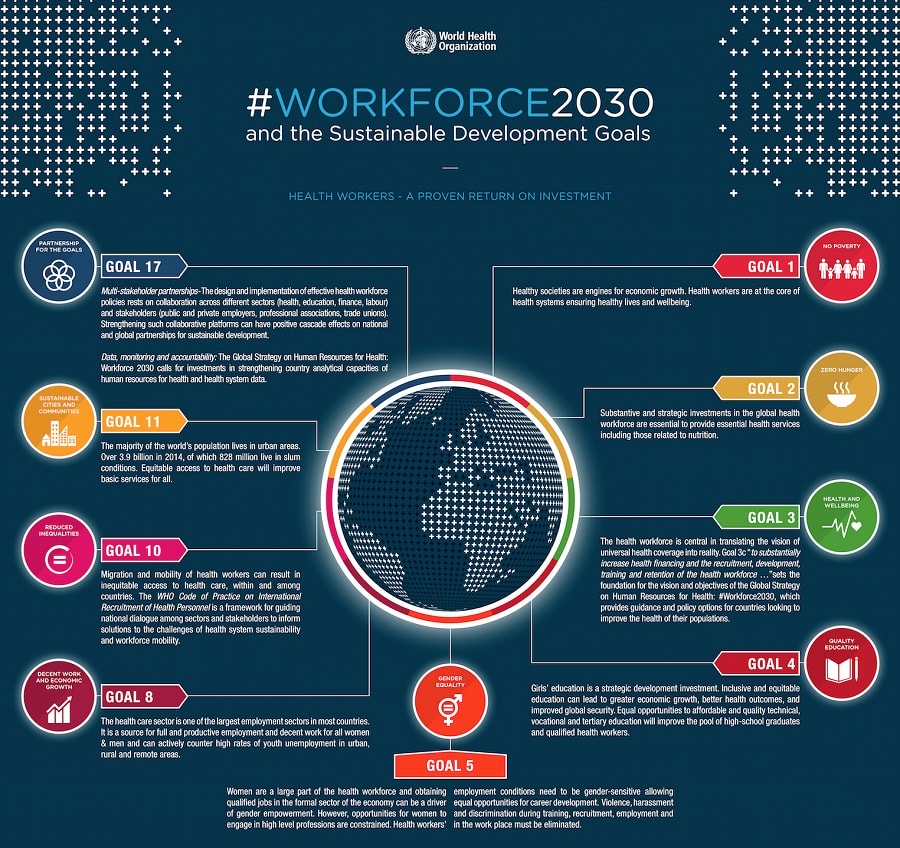

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda gives recognition to Universal Health Coverage (UHC) as key to achieving all other health targets. SDG 3 (c) sets a target to:

“substantially increase health financing and the recruitment, development, training and retention of the health workforce in developing countries, especially in least-developed countries and small island developing States”.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and its partners developed the Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030 (GSHRH) to accelerate progress towards UHC and the SDGs by ensuring equitable access to health workers within strengthened health systems.

Resolution (WHA69.19 adopted May 2016) urges Member States to consolidate a core set of HRH data with annual reporting to the Global Health Observatory, as well as progressive implementation of National Health Workforce Accounts to support national policy and planning and the GSHRH’s monitoring and accountability framework.

An article in the well-respected BMC journal entitled “Global Health Workforce Labor Market Projects for 2030”, put it this way:

“Policymakers must allocate resources and set priorities today based on expectations of future need and capacity to support health workers. Our projections of health worker demand show that predicted trends in the labor market will likely enable many countries to employ more health workers, but that the supply of health workers will not keep pace for about half the countries in the world.”

By 2030, they estimate a huge shortage in relation to net global demand: over 15 million health workers. They expect labor shortages to be most severe in middle-income countries and for the East Asia and Pacific region. The latter is anticipated to have a large increase in demand due to relatively more robust economic growth, rapid population growth and aging, and modest social protection for OOP private health spending.

Surprisingly low-income countries, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, are expected to experience the smallest shortages. But that is because neither the supply of, nor the demand for workers is expected to grow substantially.

What is Needed to Solve the Crisis

The SDGs present an aspiration which will require countries to cooperate and not compete. Simply put, many countries will need to increase health workforce training, whether pre-service or in-service, adopt new evolving knowledge and teaching methods, and allow private institutions and entities which have the wherewithal, and meet reasonable licensing and accreditation standards, to contribute.

Furthermore, the LMICs need to examine options to retain skilled health professionals at home, whether with better living and work environments, some form of bonding, or other arrangements.

On the demand side, developed countries need to look to their own commitments to produce what they need, become less aggressive in recruiting talent from LMICs which themselves are desperately needing such competency. This would be of benefit to all—as we know viruses know no walls, and infections do not stay in one place.

Featured Image: A male nurse attends a patient at the emergency room in the San Juan de Dios public hospital, in Guatemala City September 2009. Photo: Maria Fleischmann / World Bank