On January 21, the EU Commission will decide whether to classify gas and nuclear power as “sustainable”. This is a very big deal for a lot of big corporations in the energy industry – read fossil fuels producers. Are they about to take pride of place in the EU Fit-for-55 policy package, displacing the “real green” energy sources like solar and wind power and attracting all the available investment funds?

At Cop26 last November, President Macron of France presented himself as a nuclear power champion, announcing, that after decades of no investment in nuclear energy, he would relaunch the construction of nuclear reactors in France:

The last meeting of the European Council in December 2021 gave mixed results, showing Europe in disarray over energy. The 27 EU leaders couldn’t agree on what policies to adopt against the energy crisis that is driving up prices for both gas and electricity across Europe and alarming European businesses and families.

The argument was raised as to whether nuclear energy and gas should or should not be included among clean energies in the mix of energy sources proposed by the EU Commission to achieve the Fit-for-55 climate goals. As might be expected, for France whose electricity is largely derived from nuclear plants and who plans to upgrade and expand its nuclear fleet, nuclear power should be labeled green; for Germany and Austria, it shouldn’t.

Given this paralyzing standoff, the EU Commission as often happens in such cases, stepped in, finding a power void where it could function (semi)-autonomously. And by the end of this month, the EU Commission is expected to settle the argument. Since the Commission has a declared policy of “listening to all parties” before taking any decision, and since big business maintains powerful lobbies in Brussels, climate activists immediately worried about the outcome.

For example, 35O. Org got on the warpath this week with a volley of emails to its supporters, pointing out that “fossil gas can be as harmful to our climate as coal” and worried that this proposed classification “could get heaps of funding earmarked for green energy”. They fear that “sustainable and safe alternatives like solar and wind energy” would be displaced, that the only real green energy sources “would lose out”. This, they wrote, could channel “billions towards dangerous energy projects and make a mockery of the EU’s Green Deal”.

Hence 350.Org’s ongoing campaign to aim a tsunami of tweets at EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen and Frans Timmermans, Executive Vice-President for the European Green Deal to stop them from giving gas and nuclear a “green” label.

This anxiety around gas and nuclear makes all the more sense if you consider the facts on the ground: Coal – the worst possible source of energy, the one that kickstarted climate change a century ago, in short, the original sinner – has roared back last summer when the pandemic dipped and gave way to economic recovery.

What is really happening: Coal is back – along with fossil fuels

More than 40 countries at the Cop26 summit last November vowed to stop using coal. There was a dispute over what “phasing out” implied, but overall, hopes were up. And a few countries, like the UK, have actually (nearly) achieved phasing out. But even at the time, there were doubts, people wondering whether coal would be really consigned to History.

Well, it now appears that it wasn’t. A report released on January 10 shows that coal jumped 17% in the US last year, compared to 2020 and globally, according to the International Energy Agency, electricity generation from coal rose a whopping 9%.

Carbon emissions naturally followed: They rose more than 6% in the US in 2021, even faster than economic growth. Things are hardly better elsewhere, as the world, emerging from the pandemic, saw the middle classes and the rich everywhere rushing to buy gas-guzzling SUVs that emit carbon like a World War II tank, driving up global sales by 10% and they now account for nearly half of global car sales.

Satellite images published by the European Space Agency tell the story as pollution returns to pre-Covid levels, for example in China:

With a post-pandemic world awash in carbon emissions, gas and nuclear deserve to be seriously considered – just in case they really are valid alternatives on the way to a sustainable energy transition.

With a post-pandemic world awash in carbon emissions, gas and nuclear deserve to be seriously considered – just in case they really are valid alternatives on the way to a sustainable energy transition.

Unquestionably, the green movement is split on this topic with some people willing to give gas and nuclear a (temporary) pass. The only thing everyone agrees on is that coal and fossil fuels must go, sooner rather than later.

So it boils down to two questions. How soon exactly? And how environmentally damaging are gas and nuclear, given that they impact the environment in very different ways?

Before we try to answer these questions, let’s remember that solar, wind, gas and nuclear are not the only alternatives. In some cases, as the example of Iceland shows, geothermal power is a valid alternative, and Iceland derives a quarter of its energy from geothermal sources. And while, as of now, few places on earth can take advantage of this kind of energy, there may be future technological discoveries or new sources of energy that we should not discount. Human inventiveness may yet surprise us.

The crucial matter of timing: The necessary changes to the overall energy infrastructure cannot be done overnight

Our global energy system is still primarily dependent on fossil fuels everywhere and the transition to renewables has barely started. In 2020, during the pandemic, renewables bucked the downward trend for fuel demand, rising by 3%; and the share of renewables in global electricity generation jumped to 29% in 2020, up from 27% in 2019. However, coal and gas still account for 60% of the global electricity supply. And since the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan in 2011, things have gotten worse in some major industrial countries rather than better.

They have gotten worse notably in Japan itself but also in Germany, when then-Chancellor Angela Merkel, to please the public outcry over Fukushima, rushed to renounce the nuclear option without a full review of the implications.

Even though Germany is committed to renewables and the green transition, the use of coal inevitably went up, as the only way to meet demand – and it has led to thousands of deaths from local air pollution.

As for Japan, it shut down its nuclear plants and turned to coal, creating clouds of pollution that are now, like in Germany, statistically linked to thousands of deaths.

Aside from the wrong decisions taken in reaction to Fukushima, there is no doubt that the overall energy infrastructure needs to change – and, unfortunately, that’s something that cannot be done overnight.

And here is where natural gas comes in as a winner: The infrastructure is largely in place, gas is immediately available everywhere, or nearly so. It is true that Germany’s Nord Stream 2 pipeline with Russia is still not open (awaiting local permission from the regulators) and it won’t bring gas to Germany for several more months – probably not before the winter is over.

Nuclear is not so lucky compared to gas: Either the infrastructure needs to be built – and that takes a long time, nuclear plants require several years. Or it’s been around for a long time, several decades, and in that case, some reactors can become obsolete. The case in France that from the start chose the nuclear option and is heavily dependent on nuclear energy (for around 70% of the total) – and is now grappling with the issue of having to shut down some of the older plants and upgrade.

As the Fassenheim example above shows, decommissioning a nuclear power plant takes time (some 20 years) and is costly (in this case between 350 and 400 million Euros).

The transition to clean energy inevitably will take time for structural reasons. On the way to a sustainable world, both gas and nuclear can be viewed as desirable transitory stages as they are less damaging to the environment than coal and fossil fuels – hence, turning to them is better than proceeding with business-as-usual.

China, despite its pledge at Cop26 of stopping to build coal plants in other countries, has set a poor example, re-launching coal production:

To sum up: Gas and nuclear are valid halfway houses on the way to full dependence on renewables. But from a policy standpoint, they should not be viewed as final end-points: Equal attention, policy support and funding should continue to go to renewables so that gas and nuclear do not displace them.

Hopefully, the European Commission when deliberating how to label gas and nuclear will pay attention to this aspect and preserve renewables as an investment priority. Only with appropriate policy buffers will there be any hope of defending the current trend towards renewables – the “real ones”, i.e. solar and wind (and possibly sea) power.

There is a risk, to be sure, that once the choice has been made to go with gas and nuclear, it may be difficult to get rid of the infrastructure that had to be built for them and move on to the “real” renewables; it is very likely that there will be a need for an additional push with appropriate policies regarding prices, costs and tax breaks so that the energy transition is not stopped in its tracks.

To some extent, the choice to go nuclear has already been made. Governments interested in nuclear energy are set to spend serious money on nuclear energy research.

The U.S. in Biden’s $1.2 trillion infrastructure package had set aside $2.5 billion for R&D. The United States is moving towards keeping its nuclear plants operating. Senator Manchin, a Democrat from West Virginia, a long-time climate denier and notorious advocate of coal and fossil fuels who has brought considerable damage to President Biden’s Build Back Better legislation, now proposes to expand the tax credit for nuclear energy, declaring: “I’m big on nuclear”.

Likewise, some countries in Europe are nuclear-positive. France will spend $1.13 billion on research with the aim of developing a new generation of small modular reactors (SMRs) to replace parts of the existing fleet. The Netherlands also sees nuclear as a valid complementary source to renewables:

As for China, it aims to surpass the US, building more than 150 new small reactors in the next 15 years to become the world’s largest generator of nuclear power within five years. It also plans to build the first molten-salt reactor that uses thorium as a fuel, instead of more radioactive plutonium or uranium, with the added advantage that thorium accumulates as a waste product in China’s growing rare-earth mines.

Impact on the environment: Gas vs. nuclear

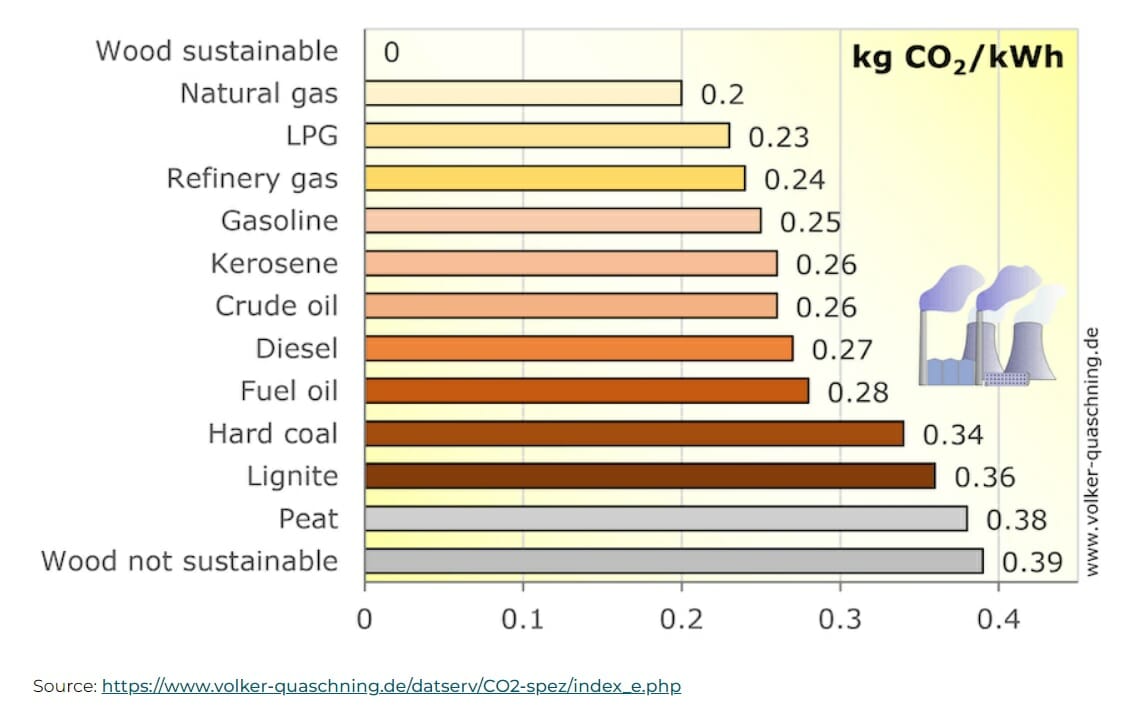

Gas is a fossil fuel plain and simple: It is only better because it burns cleaner and emits 50 to 60 percent less carbon dioxide than coal or oil-fired plants.

Natural gas is the best of the non-renewables – often described as the “the most eco-friendly power source”, but it’s far from perfect. It also releases methane and alters air quality. But its biggest problem is that it doesn’t last forever: According to Worldometers, only 52 years of natural gas reserves are left to extract.

From that standpoint, nuclear comes out the winner. Dr. Gernot Wagner, the author of “Geoengineering: The Gamble” (Polity Press, 2021) and currently teaching climate economics at Columbia Business school, has no doubts, He compellingly argued in a recent Wall Street Journal article that “Investing in the next generation of nuclear reactors could give the world an important tool for reducing carbon emissions.”

Nuclear doesn’t depend on the weather, on wind blowing or the sun hiding behind clouds (not to mention nightfall). Because, unfortunately, that is the biggest technological hurdle posed by renewables: they are intermittent. They require technical adjustments and energy storage capacities to meet spikes in demand.

In short: Nuclear is not intermittent, it’s steady and reliable – a 24/24 hour stream of energy. Better than coal or gas that can be subject to the vagaries of the market. As Wagner says, “Nuclear plants don’t depend on a steady supply of coal or gas, where disruptions in commodity markets can lead to spikes in electricity prices, as has happened this winter in Europe.”

Another advantage is the small physical footprint of a nuclear plant compared with the arrays of solar panels and wind turbines and the big dams that hydroelectricity requires – dams that generate a lot of carbon emissions when they are constructed and release large quantities of methane due to decomposing plant matter in reservoirs. Nuclear could even be considered better than “bioenergy” which, as it turns organic material into fuel, emits a lot of carbon dioxide.

Also, when building nuclear plants or when creating structures for solar and wind power, we should be aware that carbon will inevitably be emitted – which is something one tends to forget. As Wagner points out: “The level of carbon emissions generated by nuclear power is on par with solar and wind, especially when considering the complete life cycle of a plant. Both solar and wind produce entirely carbon-free electricity once they are up and running, but they require a significant carbon investment upfront.” (bold added)

To construct solar panels, metals need to be mined, and the average wind turbine contains around 200 tons of steel or more. For now, it’s not possible to produce this steel without generating carbon emissions, though it might be in the future.

So what is the problem with nuclear? It’s waste management. But there’s fortunately little of it. As Wagner says, “All of the nuclear waste produced in the U.S. since the 1950s adds up to about 85,000 tons of material. Compare that with the tens of billions of tons of carbon dioxide that would have been produced had that electricity come from fossil fuels instead.”

But there is no doubt that no matter how little there is, it’s dangerous. When the reactor reaches its end-of-life, radioactive plutonium or uranium must be disposed of safely.

Safety concerns however don’t stop there. Operating the system needs to be safe too. Research in recent years has made nuclear plants safer and as the Fukushima experience showed, most safety measures worked, the fallout was contained, nobody died and no local residents were adversely affected by radiation exposure. Admittedly, it is a matter of concern that Russia still operates nine Chernobyl-style reactors, even if they are “updated” and, hopefully, better maintained.

The investment in research makes sense: Nuclear is still not a mature technology: Best practice is far from a settled matter. There is a chance that reactors using alternative fissile materials that are easier to dispose of, like thorium, as the Chinese are doing, or natrium as TerraPower (funded by Bill Gates) is doing, could provide solutions. And the Chinese strategy of building many small reactors rather than extremely costly large ones may also give results and could be followed by France. As of now, the cost of big reactors has become prohibitive: the UK plans to spend $30 billion on two reactors, France is currently building one reactor at the cost of $21.5 billion and the U.S. is spending $28 billion on two reactors.

When considering new policies for nuclear and gas, the European Commission will need to be careful not to turn them into appetizing investments likely to displace the needed deployment of solar and wind power. Environmentalists and climate activists should demand a more accurate classification to avoid downgrading the renewables, preserving their pride of place as a priority, but recognizing the role of gas and nuclear in the sustainable energy transition.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — Featured Photo: Nuclear power plant, Grohnde Source: Pixabay