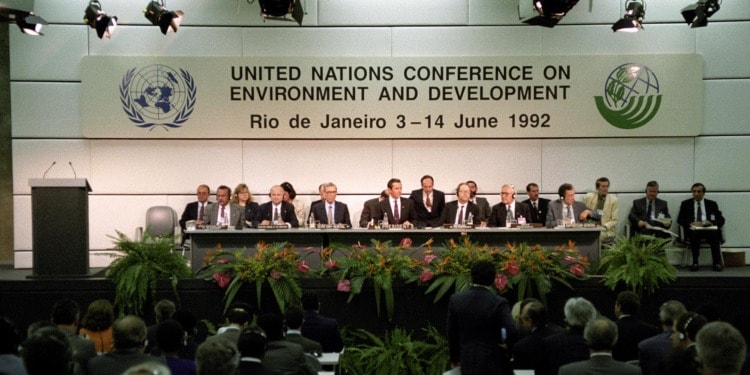

International environmental agreements (IEAs) have long played a central role in addressing global environmental challenges and managing shared natural resources. Since the pivotal Earth Summits in Stockholm (1972) and Rio de Janeiro (1992), the number of IEAs has grown significantly, with recent estimates suggesting a cumulative total of around 3,600. These treaties span various issues such as climate change, marine pollution, agriculture, migratory species, fisheries, transboundary watersheds, energy, waste management, and forest preservation.

Every UN Member State has signed at least one IEA, demonstrating their near-universal acceptance. Leading participants such as Australia, Canada, Japan, the EU Member States, the Russian Federation, and the US have each ratified over 100 IEAs since 1945.

Despite these striking numbers, environmental degradation is worsening. One reason may be that many treaties struggle to remain effective as scientific knowledge and socioeconomic and environmental conditions shift. The static frameworks of some of these treaties, which fail to anticipate emerging challenges, highlight a critical need for more dynamic and forward-looking mechanisms in international environmental lawmaking.

The need for and challenges to adaptability in IEAs

Environmental problems are not static. They evolve in complexity, scale, and impact over time. To complicate matters further, issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution are not isolated. They form part of broader, dynamic processes shaped by various economic, social, and technological factors. The interconnectedness of these problems means that addressing one issue sometimes has unintended consequences on others, creating feedback loops that can exacerbate degradation.

Advancements in scientific understanding frequently uncover previously unknown or underestimated threats, exposing gaps in existing treaties. A prime example is the Montreal Protocol, which was initially designed to phase out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). As research progressed, it became evident that other substances, such as hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), also contributed significantly to ozone depletion. The Protocol’s ability to integrate new scientific insights through amendments has been instrumental to its success.

While enhancing the adaptability of IEAs is crucial for their long-term success, several challenges hinder progress and cannot be easily overcome. Political resistance is a major obstacle, as countries often view amendments as threats to economic stability or infringements on sovereignty. Negotiating updates to IEAs is also inherently complex and time-consuming, requiring consensus among parties with diverse interests and varying levels of vulnerability to environmental issues. This diversity makes compromise difficult, delaying or even preventing necessary reforms.

Further, stability is sometimes seen as a necessary feature of international treaties, providing legal certainty and predictability for parties. Financial constraints are another significant barrier. Many developing countries lack the financial resources to implement treaty obligations or respond to emerging environmental challenges. Without sufficient funding, these countries struggle to fulfill their commitments, ultimately weakening the overall effectiveness of IEAs.

How to enhance IEA adaptability?

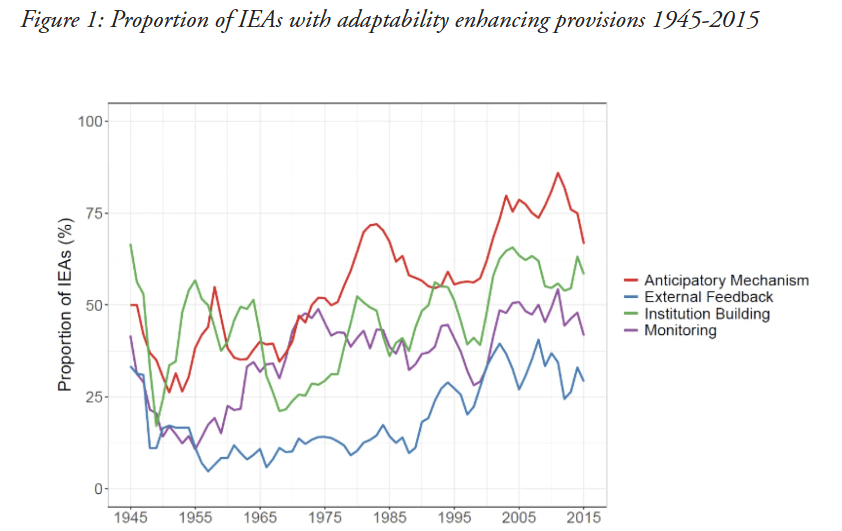

For treaties to remain effective over time, they must incorporate mechanisms that allow for adjustments based on new scientific insights, technological advancements, and changing political or socioeconomic contexts. Several mechanisms can enhance the adaptability of IEAs: anticipatory procedures; external feedback; monitoring; and institution building. Research has shown that some of these mechanisms are statistically linked to more frequent treaty adaptations.

Anticipatory procedures are one such mechanism, allowing treaties to account for future changes through provisions for amendments, protocols, and annexes. These mechanisms enable treaties to expand their scope, introduce new obligations, or adjust existing commitments as circumstances evolve. They provide a built-in capacity to address unforeseen challenges without requiring a complete renegotiation of the treaty.

Monitoring and reporting systems facilitate the collection and analysis of data on treaty implementation, allowing parties to assess compliance and evaluate effectiveness. By identifying areas where adjustments are needed, monitoring systems provide a critical foundation for informed decision making and treaty improvement.

External feedback mechanisms also play a pivotal role in maintaining treaty relevance. By integrating input from non-state actors – civil society organizations (CSOs), scientific institutions, and businesses – treaties can better respond to real-world conditions. These mechanisms provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of treaty provisions and offer recommendations for enhancements. Additionally, they contribute to the legitimacy and accountability of IEAs by ensuring that diverse perspectives are represented in both negotiations and implementation.

Related Articles: INC-5: Ambitious Countries Are Failing the Planet | What You Need to Know About the UN’s Draft Global Plastics Treaty

Institutional bodies, such as Conferences of the Parties (COPs), secretariats, and subsidiary bodies provide the structural framework for regular decision making, enabling parties to meet periodically to address emerging challenges and refine treaty provisions.

The inclusion of adaptability provisions in IEAs has evolved since the end of the Second World War (Figure 1). External feedback provisions constitute the least popular type of adaptability mechanism whereas anticipatory provisions are included in more than half of the IEAs concluded in the same period.

Policy recommendations

To enhance the adaptability of IEAs, policymakers could consider the following recommendations.

1. Strengthen monitoring and reporting systems: All IEAs should include mandatory reporting requirements that detail countries’ progress toward meeting their obligations. These reports should be reviewed by independent expert panels, which can provide objective assessments and recommendations for improvement. Regular updates to treaty commitments, based on the latest scientific data, technological advancements, and external feedback should be built into the treaty framework.

2. Promote stakeholder engagement: Policymakers should institutionalize stakeholder participation in treaty processes by creating advisory committees that represent diverse perspectives. Platforms for dialogue between stakeholder committees and policymakers should also be institutionalized. Providing technical and financial assistance to stakeholders – particularly those from underrepresented or resource constrained groups – can empower their meaningful participation and ensure their contributions effectively inform treaty processes.

3. Incorporate flexible commitments and targets: Fixed commitments and rigid targets can become outdated or unachievable as new information emerges or conditions change. Flexible commitments allow countries to adjust their obligations in response to new scientific data, technological advancements, or shifts in national circumstances. Flexible targets, such as the Paris Agreement’s nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and the Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD) National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs), enable countries to raise their ambition over time while ensuring that treaties remain relevant in a dynamic global landscape.

4. Ensure financial support for treaty adaptation: Policymakers should leverage international funding mechanisms, such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF), to provide financial support for treaty implementation and adaptation efforts. Treaties should also include more precise and binding provisions for capacity building and technical assistance to help developing countries meet their commitments.

5. Build strong institutional capacities: Policymakers should prioritize the creation of institutional bodies, such as COPs and secretariats, in all new IEAs with adequate human and financial resources. These institutions should be empowered to oversee treaty implementation, facilitate dialogue between parties, and provide technical support for treaty adaptation efforts.

6. Create club goods: IEAs may enable policymakers to establish “club goods” to incentivize ambitious environmental action among a core group of committed countries. For instance, linking environmental commitments with trade advantages offers tangible benefits for members, making participation more attractive. After establishing success and gaining visibility, the coalition can open its doors to new members, provided they meet the group’s environmental standards.

Conclusion

Many scholars have expressed concerns about the capacity of IEAs to effectively address global environmental challenges. However, not all environmental governance efforts have been unsuccessful. Critics often evaluate IEAs based on their ability to directly solve environmental problems, but effectiveness can and should be assessed in broader terms. For instance, IEAs can generate regulatory frameworks and institutional infrastructure (outputs) or influence the behavior of key stakeholders and countries (outcomes). These changes, though indirect, may contribute to tackling environmental challenges over time.

Assessing the true impact of IEAs is inherently intricate. Limited baseline data from the period before many agreements were established complicates efforts to measure progress. Determining what would have occurred in the absence of these agreements is equally challenging. These factors make it critical to evaluate IEA performance with caution and nuance, avoiding overly simplistic judgments.

The essence of international environmental law lies in finding pragmatic compromises that incrementally advance progress, even if the results fall short of ideal solutions. The strength of IEAs often lies in their ability to balance diverse perspectives and interests, fostering collaboration and gradual improvements rather than delivering immediate or perfect outcomes. This pragmatic approach underscores the value of IEAs as tools for incremental but meaningful environmental progress.

As global environmental challenges grow more complex and urgent, international IEAs must remain adaptable to changing conditions. By incorporating adaptability into treaty design, engaging a wide range of stakeholders, and ensuring financial support for treaty adaptation efforts, policymakers can ensure that IEAs remain dynamic and impactful tools for addressing the evolving environmental crises of our time.

** **

This article was originally published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and is republished here as part of an editorial collaboration with the IISD. It was authored by Noémie Laurens, ENB writer and postdoctoral researcher at the Geneva Graduate Institute.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) – or Earth Summit, June 3, 1992. Cover Photo Credit: United Nations.