In these times when developed economies are desperately trying to deal with the impact of COVID and the need to provide public sector financing for their own recovery from the pandemic, it is remarkable that the World Bank received a historically high amount of funding for replenishing the International Development Association (IDA), its soft window for developing countries – better described as the World Bank’s “fund for the poor”. The funds will be delivered to the world’s 74 poorest countries under the 20th replenishment (IDA20) program.

The World Bank announced on December 15 that, following a 2-day meeting hosted virtually by Japan, it had received pledges amounting to $93 billion – the highest ever in its 61-year history. The funding comes at a crucial time for the poor: The World Bank estimates that the global pandemic could push between 55 and 63 million people in IDA countries into extreme poverty.

Due to the urgent development needs of IDA countries, the replenishment was advanced by one year. IDA20 will cover a 3-year period, from July 1, 2022, to June 30, 2025, with a funding package designed “to help low-income countries respond to the COVID-19 crisis and build a greener, more resilient, and inclusive future”.

A complex financing package that has a leveraging benefit

The financing package is complex: It is sourced from $23.5 billion of contributions from 48 high- and middle-income countries together with financing raised in the capital markets, repayments, and the World Bank’s own contributions.

IDA has a unique leveraging model that enables it to maximize donor resources: Every $1 that donors contribute to IDA is now leveraged into almost $4 of financial support for the poorest countries. At the end of 2021, IDA had $174.8 billion in equity and around $16.5 billion in outstanding market debt.

Japan, the host of the online donor meeting, made a record $3.4 pledge to IDA20. “Now is the time for global solidarity,” Japanese Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki told the meeting. The top 10 country pledges in the previous IDA replenishment, IDA19, shows that Japan was the second-largest contributor, right after the UK:

Note that the US used to be a top contributor, reaching its highest point with the Obama administration when it contributed around $3.9 billion. Final figures for IDA20 are not yet available.

What is interesting about the IDA leveraging or “hybrid financing model” is the importance it automatically gives to the World Bank itself, as it manages to not only match the donation from member countries but triple it. This video explains how IDA hybrid financing works, capturing private sector funds:

Hence the importance of the Bank document that outlines what it will do with this funding. The objectives and modus operandi were laid out in a World Bank document published on June 11, 2021, with the title IDA20 Special Theme: Human Capital.

What the IDA20 financing package will do

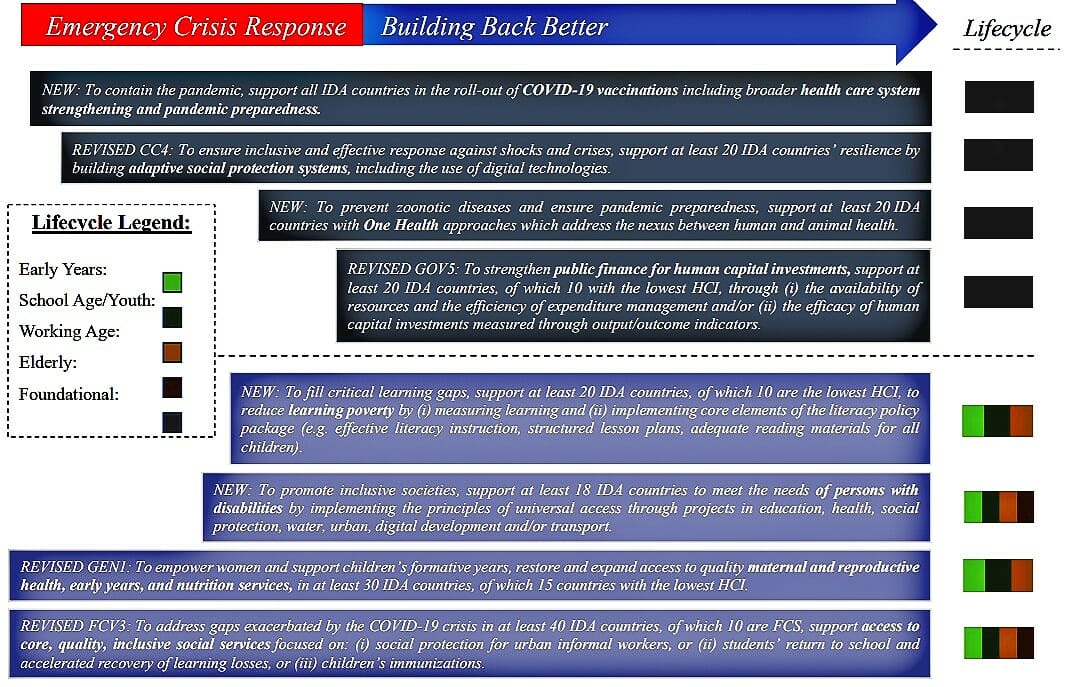

The document goes into great detail as to what the goals are and the means to achieve them – and the focus, as shown in the table below, is recovery from the pandemic and building back better:

Policy Commitments in the IDA 20 Framework and Lifecycle

The objectives, as expected, are to support all IDA countries in the roll-out of Covid-19 vaccinations, including strengthening health care systems and pandemic preparedness. This will build on the strong achievements of the previous financing package, IDA19, which saw nearly 70 countries benefiting from IDA financing for vaccines, health professionals’ training, and hospital equipment.

But what is new and notable in IDA20 is the inclusion of One Health, with the objective of supporting at least 20 IDA countries with a One Health approach “to address the nexus between human and animal health”.

Also, of particular interest is the new and important emphasis on “prioritizing investment in human capital”: The funding package will address “learning poverty” to fill “critical learning gaps” in at least 20 IDA countries, and “promote a more inclusive society” by meeting the needs of persons with disabilities in at least 18 IDA countries. Other major target groups are women and children, as in past IDA packages, but with revised approaches to ensure greater impact.

A continued emphasis on governance and institutions, debt sustainability, and digital infrastructure interventions is meant to help foster economic and social inclusion. The idea is to address major development challenges such as gender inequality, job creation, and situations of instability and violence.

The climate emergency is not forgotten. A substantial portion of the funding will address climate change, with a focus on helping countries to adapt to rising climate impacts and preserve biodiversity. It will build on the achievements of IDA19 that in fiscal year 2021alone helped 62 countries institutionalize disaster risk reduction plans.

Although IDA20 is designed to support countries globally, more will go to Africa, which is set to receive about 70 percent of the funding. Since IDA20 is designed to tackle situations of fragility, conflict and violence, the Sahel, the Lake Chad region, and the Horn of Africa will be included.

The overall IDA20 target group is huge: 400 million people are expected to receive essential health and nutrition resources, and social safety nets programs are set to reach as many as 375 million people.

Will IDA20 deliver?

There is no question that a considerable number of developed countries have pledged funding that constitutes a historic and very substantial increase in the Bank’s soft window for developing countries. We can all agree that this is a step forward, a tribute to recognition that global public issues, such as pandemics and climate change do not stop at borders or physical boundaries. And, that the World Bank, as the oldest global development financing institution, while flawed as is any mega institution, is still the go-to place.

That said, there is a need to make sure that:

(i) these pledges are met over the replenishment period,

(ii) that these commitments are additive to donor country development assistance, and not a way to simply say “we’re giving enough to the Bank”, and

(iii) that the funds are committed, disbursed, and appropriately spent in a recipient country.

The first is easy to track once the replenishment is formalized. The second is much more difficult and in some respects requires qualitative assessments, in determining in each donor case whether these amounts substitute for what “would have been given otherwise”. And the third will depend on Bank professionals, working with country counterparts, to agree on the objectives and design sound instruments to deliver as intended, and application of existing Safeguards on environmental, health, social and matters.

Bank past evaluations provide guidance in this regard. In fact, the World Bank is a premier institution with regard to project and programme evaluations, having set up a wholly independent structure for evaluation. This is unlike any UN technical agency: All of those, including the more ancient and reputable ones like FAO and the World Food Programme have not instituted independent evaluation offices (they all report to the agency head).

With the World Bank, things are different. Project and programme evaluators do not report to the head of the Bank, they report directly to the governing bodies, i.e. the member countries. This has established them as free agents whose judgment can be trusted. And, as a notable side-effect, the World Bank – including IDA – has acquired a sterling reputation, encouraging donors to entrust their funding to it.

That said, providing assistance has never been an easy business. IDA20 implementation will be a challenge for both the country leadership and implementing staff as well as that of the Bank to assure effectiveness and governance is executed as intended.

The weakness of public aid: Limited funding compared to what the developing world needs or to what the private sector spends

Not only is the management of assistance to developing countries challenging. The public sector – including international institutions like the World Bank – are seriously hampered by continued lack of funding in relation to needs. $93 billion sounds like a lot, but actually, it’s very little.

Consider how much the private sector is willing to spend on silicon chips so that your cell phone is working for you and your car battery doesn’t die down. We’ve all heard of the silicon chip shortage this year and how expensive it is to produce them. For example, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. is spending a record $100 billion over a three-year period to grow capacity.

That’s just one corporation spending roughly the same amount over the same time period as what will become available to IDA (if all goes well). But of course, the investment is for our cell phones – not social justice or helping the poor achieve dignity.

Consider what happened at COP26 with the Green Climate Fund and requests by the developing world for climate compensation – requests that were never met, either in Glasgow now or in all the years before, since the climate fund was first established in 2010. The yearly amount requested from the developed world was $100 billion – only around 80% of that funding was ever delivered.

As Greta Thunberg famously said: “It is not a secret that COP26 is a failure. It should be obvious that we cannot solve a crisis with the same methods that got us into it in the first place.”

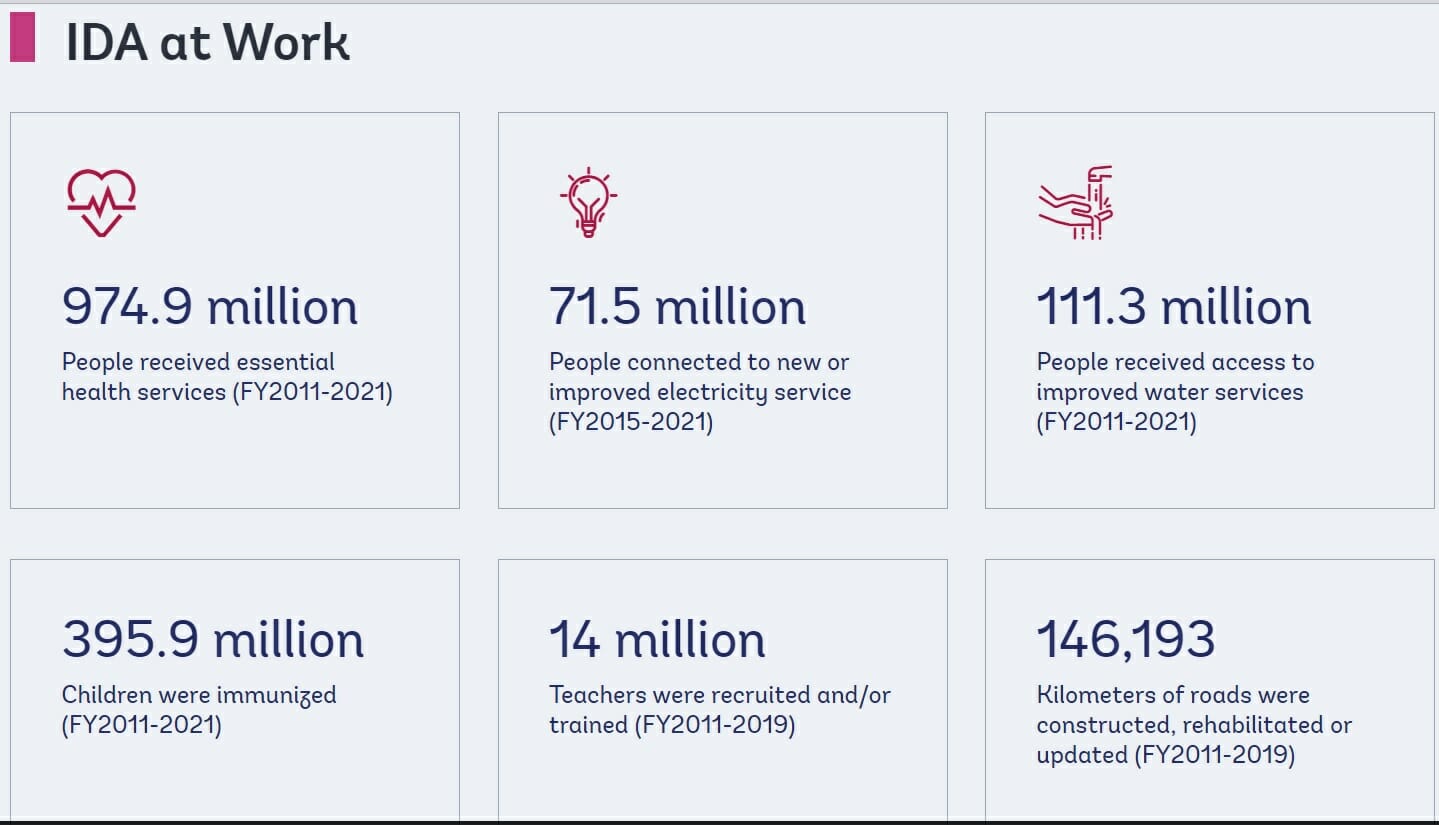

This, of course, is a simplification. Thunberg hits the nail on the head but she misses out on the details. And among the not insignificant details are organizations like IDA that do work towards improving the world. In fact, over the past decade, IDA has made multiple concrete achievements, and IDA20 can be expected to add to them:

So it would appear to be important to strengthen the actions of such international organizations. And $93 billion for 3 years is good, but not good enough. More is needed – for IDA and all other similar funding, in particular the Green Climate Fund. Regarding the latter, it would do well to follow the hybrid financing model of the IDA to leverage the power of private funding – and perhaps some sort of cooperation arrangements with other international funding entities, IDA included, should be envisaged.

Because there’s an urgent need to leverage public aid and bring it to the level of funding the private sector routinely spends to maintain the lifestyle of citizens in developed countries and of better-off citizens everywhere.

With the contribution of Richard Seifman, Senior columnist.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: IDA blog – Why IDA matter and how it can realize its full potential: An evaluator’s take