For the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty on October 17th, UN chief António Guterres described current poverty levels “a moral indictment of our times.” The culmination of major challenges, including the Covid-19 pandemic, conflict, and climate change, have led to the first rise in extreme poverty in two decades. An additional 119-124 million people were pushed into extreme poverty in 2020. Guterres proposes a three-pronged global recovery approach to “Building Forward Better.”

The year 2020 saw an increase of 119-124 million people falling into extreme poverty, of whom 60% are in Southern Asia. This dramatic drop was traced to the Covid-19 pandemic that has wreaked havoc on economies and societies around the world and reversed much of the progress made in reducing poverty. The clearest argument for this is that, prior to the pandemic, poverty rates were declining.

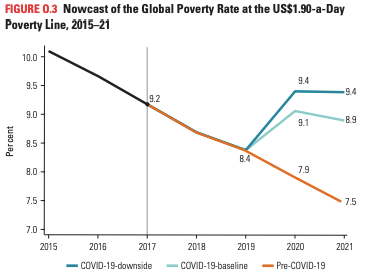

Yet the world was not on track to achieve the goal of ending poverty by 2030 due to growing rates of extreme poverty coming from conflict-affected countries, and the growing economic threat posed by climate change. Although the number of people living on less than $1.90 per day dropped from 10.1% to 9.3% between 2015 and 2017, the rate of reduction for poverty was already slowing down to less than half a percentage point annually between 2015 and 2017, compared with one percentage point annually between 1990 and 2015.

In short, Covid-19 has simply exacerbated this already decelerating trend and has become the newest most immediate threat to poverty.

FIGHTING TWO BATTLES AT ONCE: POVERTY AND INEQUALITY

Issues of poverty and inequality are severely intertwined. The Covid-19 crisis has disproportionately affected women and young people, as well as intensified the well-documented inequalities between the global North and the global South. Consequently, more than 90 million people may have been driven into extreme poverty in 2020 due to the pandemic alone.

The United Nations found that the several lockdowns and other related public health measures implemented due to the pandemic had worsened the gender gap among the working poor. The health measures enforced over the past year and a half have severely affected the “informal economy”, defined by the diversified set of economic activities, enterprises, jobs, and workers that are not regulated or protected by the state, in which much of the working poor are employed.

Working poverty is defined as an employed person living in poverty, likely caused by low earnings, and inadequate working conditions.

Although the gender gap in working poverty has narrowed over the years, a substantial gap persists in many parts of the world, particularly in the least developed countries. One third (33.5%) of employed women were living in poverty in 2019, compared with 28.3% of employed men. Whilst young workers are twice as likely to be living in poverty as adults. As the Covid-19 crisis has had a disproportionate impact on the livelihoods of women and young people, it is likely that these longstanding disparities are further exacerbated.

Related Articles: COVID, Climate Crisis and Conflict Create 150 million ‘New Poor’ | #Startups4Good: Companies Looking To End Poverty by 2030

Furthermore, António Guterres argues that vaccine inequality has caused the burden of the Covid-19 pandemic to fall disproportionately on poorer countries. Several Covid variants have mutated, he said, condemning the world to millions more deaths and prolonging an economic slowdown that could eventually cost trillions of dollars.

He told a panel at the International Monetary Fund that global solidarity has been “missing in action”, reiterating that people in conflict zones and fragile states were suffering worst of all.

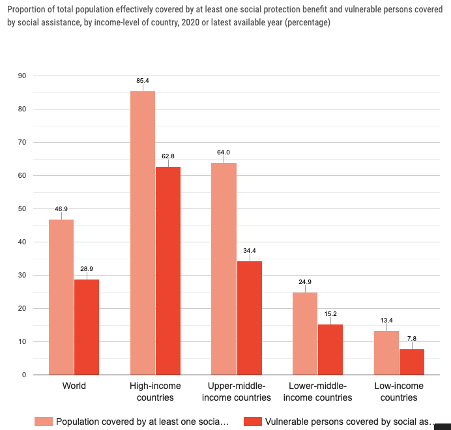

Lastly, whilst social protection measures are shown to be fundamental to preventing and reducing poverty across the life cycle, by 2020 only 46.9% of the global population was covered by at least one social protection, UN Stats show. This leaves 4 billion people without a social safety net. Before the pandemic, most of the population (85.4%) in high-income countries was effectively covered by at least one social protection benefit, compared with just over one tenth (13.4%) in low-income countries.

Scholars found that if current within-country inequality remains unchanged and that GDP per capita growth follows the World Bank forecasts, then the number of extreme poor will remain above 600 million in 2030, resulting in a global extreme poverty rate of 7.4%. However, If the Gini index (synthetic indicator that captures the level of inequality for a given variable and population) in each country decreases by 1% per year, the global poverty rate could be reduced to around 6.3% in 2030. That is, the equivalent of 89 million fewer people living in extreme poverty.

In short, the fight against poverty must also be accompanied by a battle against inequality to render any solution efficient.

‘BUILDING FORWARD BETTER’ – A RESPONSE

On October 14, António Guterres published a message for the International day for the Eradication of Poverty, outlining a three-pronged global recovery approach to ‘Building Forward Better’:

- The recovery must be transformative, with stronger political will and partnerships to achieve universal social protection by 2030. Guterres added that returning to pre-pandemic endemic structural disadvantages and inequalities was most certainly not the aim. Investing in job re-skilling for the green economy that promises high growth rates, and investing in quality jobs in the care economy, could promote greater equality and ensure everyone receives the dignified care they deserve.

- The recovery should be inclusive, so as to deter an uneven recovery whereby much of humanity could be left behind, increasing the vulnerability of already marginalised groups, and pushing Sustainable Development Goals even further out of reach.

“The number of women in extreme poverty far outpaces that of men. Even before the pandemic, the 22 richest men in the world had more wealth than all the women in Africa – and that gap has only grown… We cannot recover with only half our potential,”

— UN Secretary-General António Guterres

Women’s poverty arises from:

💢Lack of opportunities

💢Gender discrimination

💢Restrictive legal statutes

💢Unequal wagesOn #EndPoverty Day, let’s speak up for women’s access to economic resources! pic.twitter.com/yPXluD477i

— UN Women (@UN_Women) October 17, 2021

The UN chief said economic investment must target women entrepreneurs; formalise the informal sector; focus on education, social protection, universal childcare, health care and decent work; and bridge the digital divide, including its deep gender dimension.

- Finally, the recovery must be sustainable to build a resilient, decarbonised and net-zero world.

All three suggestions appear eminently sensible and doable. But will they be enough to eradicate extreme poverty by 2030?

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Extreme poverty is on the rise for the first time in two decades, Covid-19 has become the newest most immediate threat. Featured Photo Credit: Taylor Brandon.