Speaking of “fragmentation risks to the Euro system” sounds highly technical and miles away from anything threatening the Euro or our daily lives. Yet, with rising prices caused by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine and the risk of devastating inflation, that is precisely what is at stake here. And that is the problem the European Central Bank has just set out to address.

Yesterday, June 15, was a fateful day: The US Federal Reserve held its own meeting to address rising prices in America, and raised its benchmark interest rate by 0.75 percentage point, a level not seen in 20 years; the European Central Bank (ECB) Governing Council unexpectedly held an ad hoc emergency meeting and made an announcement that replicates in its own way Mario Draghi’s famous catchphrase: “whatever it takes” to save the Euro – that was ten years ago, and at the time Draghi was at the helm of the ECB as the sovereign debt crisis following the Greek debt debacle raged on.

Today, the Euro is not about to collapse, but European monetary policy and the ECB’s capacity to control inflation are certainly at high risk, hence the Governing Council’s sudden meeting and if this time the language in the press release is not as punchy as Draghi’s, it is succinctly clear and to the point announcing a new monetary tool, an “anti-fragmentation instrument”:

“The Governing Council decided to mandate the relevant Eurosystem Committees together with the ECB services to accelerate the completion of the design of a new anti-fragmentation instrument for consideration by the Governing Council.” (bolding added)

The next ECB Governing Council on monetary policy is scheduled to take place on July 21 when it is expected that interest rates will be raised – it is the only rational monetary policy available to fight inflation (see video below) – and therefore the expectation is that this new monetary instrument to address fragmentation should be ready by then.

What is the problem of “fragmentation” of the sovereign bond markets and why an “anti-fragmentation instrument” is needed

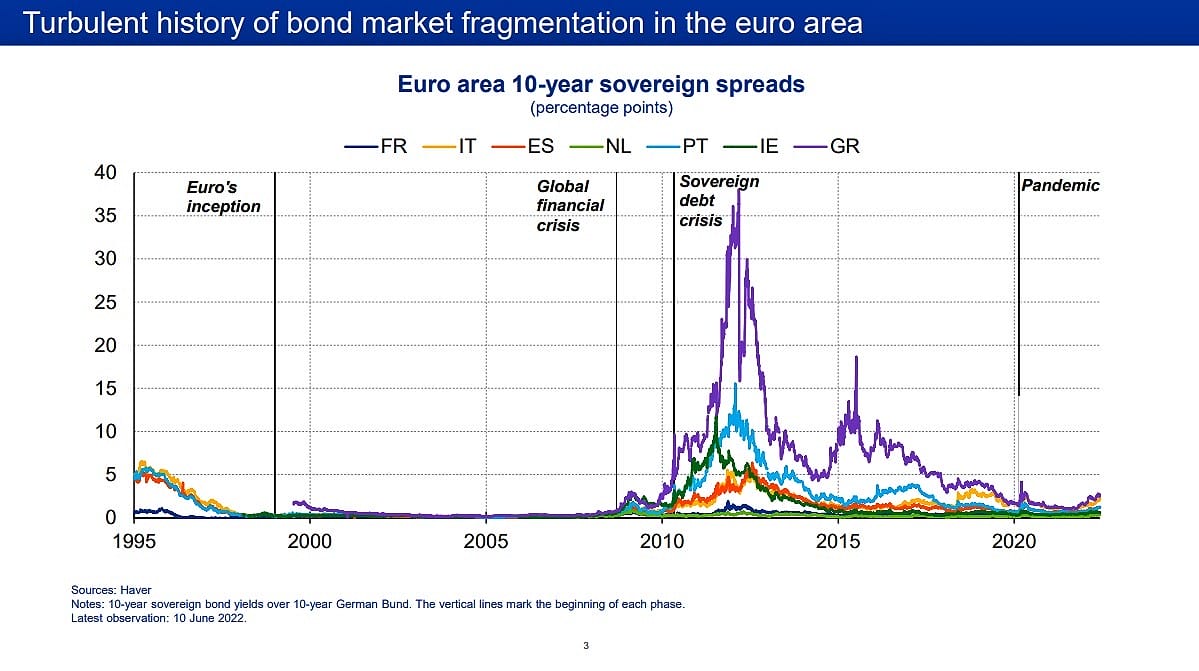

The “fragmentation” problem in question refers to the big jumps in sovereign bond spreads between countries, with Germany generally being the benchmark of stability while Italy and EU “peripheric” countries that are more debt-ridden and volatile see their sovereign bond yields shoot up as investors run away from them.

And recently, sovereign spreads have suddenly started to widen again, immediately recalling the worst days of the Euro, with the ten-year rate for sovereign bonds in Italy exceeding 4% for the first time since 2014: On June 14, the BTP-Bund spread (i.e. Italian vs. German government bonds) had widened by 100 base points in two months, showing a strong acceleration of this trend over the last few sessions.

Of course, this is not the first time it happens. Since its inception, the Euro has suffered several uncomfortable episodes of this kind, starting with the Global financial crisis in 2008 and followed by the Greek debt crisis of 2010 that expanded into a major sovereign debt crisis shaking the Euro and leading to Draghi’s famous pronouncement, as this graph shows:

For a central bank like the ECB tasked with defending the Euro, fragmentation in sovereign bond markets is a big problem: It means its monetary policy doesn’t work, it gets defeated by uncontrolled spreads among EU member sovereign debts, with investors panicking and taking refuge in the “best” bonds, i.e. Germany.

It took more than Draghi’s catchphrase to reign in the sovereign debt crisis: A series of specific instruments was launched by the ECB; first, the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme which addressed the sharp sell-off in bonds in many parts of the Euro area; next the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and later the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) to rescue funds for states; and finally, the building blocs of a “banking union” to stabilise the European banking system and foster financial integration, starting with the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM).

When the pandemic hit in 2020 creating disturbances in the markets, the BCE was far readier than it had been in the early days of the Greek crisis in 2010; it was able to better control the disparate fiscal policies of EU members. For example, and crucially, access to OMT funds was made conditional by the ECB on countries implementing structural reform and maintaining fiscal discipline. This is an important point to keep in mind: No currency can be correctly managed and defended by a central bank unless both monetary and fiscal policies are kept in line and now the ECB has a say in any EU member country’s fiscal policies – something it didn’t have before.

Moreover, the BCE was able to successfully address imbalances caused by the pandemic as, once again, financial intermediation ceased to function, markets dried up and sovereign and corporate spreads spiraled.

What did the trick was the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) which immediately stabilised markets, restoring confidence. If you wonder why the PEPP turned out to be so effective, it was because it proved to be highly flexible, with liquidity provided when and where it was most needed.

But the EU’s reaction to the pandemic didn’t stop there. The European Commission devised a major recovery fund, the Next Generation EU (NGEU) package focused on digital and green industries, thus forcing (or should I say inspiring?) EU governments into virtuous public investments in the most promising areas for recovery and growth.

With NGEU and the recovery fund we are far from the volatile situation fifteen years ago when Greece was accused of profligacy as it allowed its public debt to balloon with, inter alia, pointless investments in the Olympic Games. Indeed, things have changed and just last month, Greece announced that it has paid back all its debt two years ahead of schedule.

But the main point here, and what is new, is that with NGEU, for the first time in the history of the Euro, the ECB finds itself with a channel for public risk-sharing at the European level: To fund the energy transition, the EU launched a record-breaking 12 billion Euro bonds programme.

A strong message from the ECB to the financial world – in the words of the German member of the Bank’s Executive Board

We are witnessing a game-changer and I’m not the one saying it: This is precisely the message sent out in a speech delivered in Paris to graduate students at Sorbonne University by Isabel Schnabel who is a member of the Executive Board of the ECB, representing her country, Germany.

And when the German member of the ECB Board speaks, one should listen.

In her speech, Schnabel drew a clear picture of how the Euro evolved, strengthened by all the measures taken by the ECB up to now. As she put it, “Since reforms under NGEU are oriented towards growth-friendly investments, it will help the EU emerge stronger from the crisis by linking financial support to measures making our economies greener and more digital.”

But ECB action doesn’t stop there: “the allocation of NGEU funds, through the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), involves a considerable degree of solidarity. Allocations are tilted towards countries with weaker GDP per capita and higher public debt ratios, thus fostering convergence and strengthening the euro area as a whole.” (bolding added)

In short, in her words, what we have now is a “stronger European monetary union architecture” but, as she acknowledged, over recent days, concerns have grown as “the increase in sovereign risk premia has accelerated, liquidity conditions have become more challenging, and daily changes in bond yields have increased.”

And the solution? Here is what she said and which immediately drew the attention of the financial world: First, she recalled that “the flexible allocation of PEPP reinvestments is one way to address fragmentation” but, she noted, it has its limits since it was meant to be temporary – linked to the pandemic. Then here comes the punchline:

“our commitment is stronger than any specific instrument. Our commitment to the euro is our anti-fragmentation tool. This commitment has no limits. And our track record of stepping in when needed backs up this commitment.

[…] We will react to new emergencies with existing and potentially new tools. These tools might again look different, with different conditions, duration and safeguards to remain firmly within our mandate. But there can be no doubt that, if and when needed, we can and will design and deploy new instruments to secure monetary policy transmission and hence our primary mandate of price stability.

[…] monetary policy will need to respond to destabilising market dynamics. We will not tolerate changes in financing conditions that go beyond fundamental factors and that threaten monetary policy transmission.” (bolding added)

Strong words that echo the ECB’s determination and yesterday’s Governing Council’s terse announcement of a new “anti-fragmentation tool”.

Exactly what this new tool will consist of is not known for now. But we should remember that often the most effective central bank tool is merely the announcement: It is the threat of monetary policy action and not the action itself as we saw yesterday with the correction of market rates as soon as this ECB emergency meeting was announced.

But one thing is certain: The architecture of the Euro has been considerably strengthened since the 2012-15 sovereign debt crisis, and with a determined Executive Board and President Lagarde at its helm, there is hope that the exit from the present crisis, while not painless, will nevertheless occur as fast as possible.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: President Lagarde coming to ECB Press conference Source: ECB