Steve Bannon is roaming Europe trying to unite nationalist populist parties, in preparation of the next European Parliament elections coming up in May 2019.

Bannon is a man to watch: alt-right guru, former investment banker, former executive chairman of Breitbart News, former CEO of Trump’s 2016 campaign, former White House strategist (for seven months), he has remained Trump’s close friend. And he is dangerously savvy: As vice-president of Cambridge Analytica, he was able during the 2016 Trump campaign to use its data to target and manipulate voters.

Last month, Bannon announced he would move to Brussels to found a new pan-European populist movement, called “The Movement”. His hope? To get all populist, anti-establishment parties in Europe to join his Movement, which he views as an umbrella “supergroup” to lead them to victory. He could just as well have used the slogan “Europe Haters, Unite!”

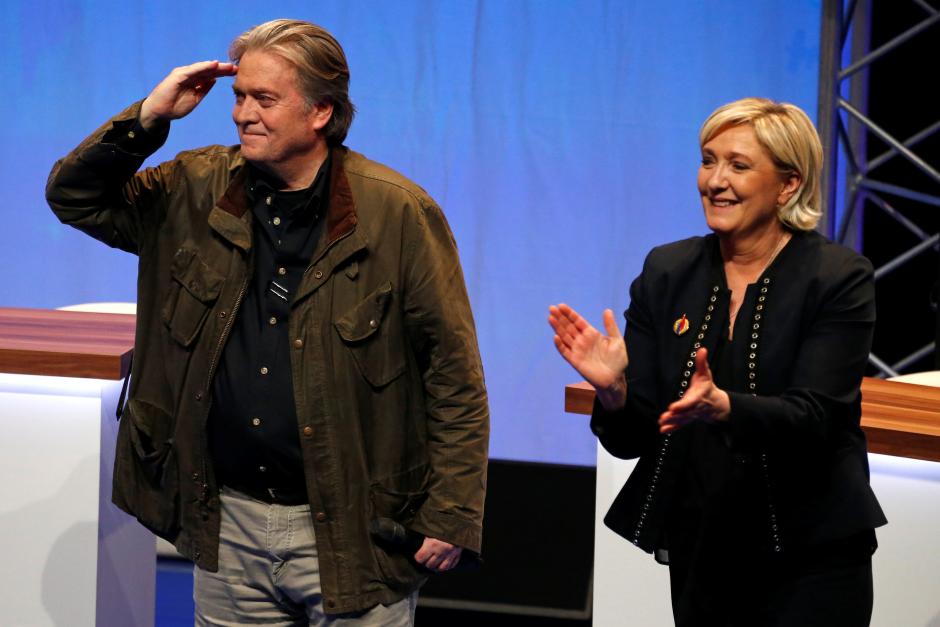

It all started a few months before, in March 2018 when Bannon was invited by Marine Le Pen to speak to her party’s annual summit meeting, the National Front congress in Lille. That’s when he realized that he had a goal cut out for himself. Bannon told the LePen crowd:

“What I’ve learned [visiting Europe] is that you’re part of a worldwide movement that is bigger than France, bigger than Italy, bigger than Hungary, bigger than all of it. And history is on our side. The tide of history is with us and will compel us to victory, after victory, after victory!”

The following video of the event is instructive:

Note how Bannon uses typical populist oratorical ploys: “Let them call you racist, let them call you xenophobes, let them call you nativists” he yells, adding meaningfully: “Wear it like a badge of honour.” A badge of honor, really? Yes! Nothing to be ashamed of! And why not?

Here’s his answer: “Because every day we get stronger and they get weaker.”

Notice how this works: He is suggesting to his audience that they are on the “right side of History”.

The last time we heard that argument, it came from the communists and the Soviet Union. They too claimed to be on “the right side of History”.

We know how well that ended. At the Berlin wall.

“Next May is hugely important,” Bannon told the Daily Beast. “This is the real first continent-wide face-off between populism and the party of Davos. This will be an enormously important moment for Europe.”

What he calls disparagingly “the party of Davos” are the political and business leaders who meet to debate world issues at the World Economic Forum, held in Davos in January of every year.

Bannon is haunted by George Soros, the financier-philanthropist of Hungarian origin and the founder of the Open Society Foundation. Since 1984, Soros has donated $32 billion of his personal fortune to shore up democracy in a 100 countries, of which some $18 billion to Eastern Europe and especially to Hungary. This is the man Bannon would like to displace in Europe – with an extreme right-wing vision in lieu of liberal democracy.

Bannon’s plan is simple. If he can get at least a third of all EU deputies in the “Movement”, they would constitute a right wing bloc in the European Parliament, enough, he argues, to be in pole position to influence EU institutions and shape Europe’s agenda.

He is relying on UK’s Nigel Farage and France’s Marine Le Pen to help him in rallying the populist leaders of Eastern Europe, particularly Hungary’s Victor Orban, the paladin of “illiberal democracy” whom he calls “Trump before Trump”. Orban plans to turn the European Parliament election into a referendum on immigration and Islam. The other major player is Poland’s Jaroslav Kaczynski, head of the Law and Justice party but Poland’s de facto autocratic leader.

Farage and Le Pen are probably Bannon’s closest friends in Europe but they are both struggling with their own demons and it’s not clear how much time and energy they can devote to rally people around Bannon’s Movement.

After playing a decisive role in winning Brexit, Farage resigned as UKIP leader, saying “I want my life back”, claiming he never was a “career politician”. After he left, UKIP collapsed and it has only regained some momentum this year with a new leader, Gerard Batten. Presently Farage is mainly a media commentator, on Fox News and on LBC, London’s commercial radio talk station. He is still a member of the European parliament, at least until March 2019. What he will do next is anyone’s guess.

Marine Le Pen had to lick her wounds after Macron defeated her in the 2017 presidential elections. Yet she had tried ever so hard. She had softened her image, famously expelling from the party its founder, her own Petainiste father in August 2015. He went, along with a series of extremists. And she managed to relax the party’s stance on anti-semitism and on civil unions for same sex couples and she withdrew the death penalty from the party’s platform. It is clear that she cannot allow Bannon to damage her new-found image.

Will the populists, wearing “racist” as a badge of honor, win the next European elections?

And if they do, how important is it for Europe’s future?

To answer this we need to first look at Bannon’s strategy which is centered on holding thirty percent of the EU lawmakers. But there are problems with this.

One, the EU Parliament is not the ultimate institution setting laws in the EU. National laws still prevail in every European’s life. Pushing the EU Parliament to the right is likely to be more symbolic than real. The effect will be limited, and in any case, not immediate.

Two, populist parties in Europe prefer to go each their own national way. France 24 did an excellent in-depth piece of journalism noting that far right leaders in Europe were not eager to follow Bannon. Dr. Peter Jackson, a senior lecturer in contemporary history at Northampton University and student of the extreme right in Britain and Europe, said that it’s “far from clear whether Bannon can be a unifying force” in Europe:

“[His] US-centric approach to issues does not mean he is going to be easily adopted by European groups that are keen to highlight their independence and deep respect for their national identity.”

European populist leaders are not really ready to band together because it would mean submitting to the will of one boss, in this case, Steve Bannon. And they don’t trust Bannon, a figure shadowed by Trump’s mad antics. This evokes images of the Ugly American, particularly now that Trump expresses ever deeper hostility towards Europe and Europeans.

It doesn’t help that Trump constantly tweets manic accusations of “collusion”, “rigged witch hunt”, calling Special Counsel Mueller a new McCarthy, when all he is doing is his job investigating Russian interference in America’s 2016 presidential elections:

Study the late Joseph McCarthy, because we are now in period with Mueller and his gang that make Joseph McCarthy look like a baby! Rigged Witch Hunt!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 19, 2018

Most Europeans are convinced that Russia interfered in America’s presidential elections and everybody knows Putin disliked Hillary Clinton and wanted Trump as President. He never made a secret of his preferences.

And it doesn’t help that America is presenting a scary image to the world, with gun battles in the streets and in schools, a rising population of homeless people, and a worrying increase in midlife mortality across all races (not just the Black and Hispanics). This has resulted in a surprising shortening of life expectancies, with the U.S. lagging behind other rich countries. The only other developed country suffering from a similar deep-seated malaise – what American doctors call the “shit-life syndrome” – is the U.K., as recently reported by Will Hutton in the UK Guardian.

Are Europeans aware of the situation in the U.S.? They certainly are, plenty of videos circulate on Facebook and YouTube. Here’s a recent one (February 2018) made by Deutsche Welle, Germany’s public international broadcaster:

Spokesman Jérôme Rivière of the National Rally (formerly Front National – Marine Le Pen’s party) recently said “We reject any supra-national entity [like Bannon’s Movement] and are not participating in the creation of anything with Bannon.” He added for good measure, “Bannon is American and has no place in a European political party.”

Bannon doesn’t realize that most far-right populists are anti-American. And getting in bed with him is risky. Alexander Clarkson, a lecturer at King’s College London told the BBC:

“If they embrace Trump, then all that anti-Americanism below the surface will turn itself against them, particularly in France.”

Any equation of populism with Trumpian politics is the kiss of death and European populist leaders are well aware of this.The latest spat with Turkey is not helping matters for Bannon.

In short, Bannon’s plan for a “super-group” of right-wing EU parliamentarian is stillborn – a fact that was quickly highlighted by the American media, the New York Times and The Atlantic among others. They highlighted that many right-wing parties were not interested. They feared cozying up with Bannon might do them more harm than good.

Unsurprisingly, Bannon is reviled by liberal EU politicians:

Steve Bannon’s far-right vision & attempt to import Trump’s hateful politics to our continent will be rejected by decent Europeans. We know what the nightmare of nationalism did to our countries in the past. We must #BanBannon! #GenerationEurope must stop him! pic.twitter.com/4VF2hiJ2bD

— Guy Verhofstadt (@guyverhofstadt) July 22, 2018

Mr. Bannon, the situation is not so simple…

Much can happen without you.

First of all, European populists don’t need Bannon to do well across Europe. As Hanno Burmester, a policy fellow at Berlin think tank Das Progressive Zentrum, which recently published an important policy brief on populism, noted:

“The sad truth is that it does not take Steve Bannon to build a strong far right in Europe. The voters are doing his job perfectly well – by not voting, and by supporting nationalist, anti-EU forces in their home countries.”

Populist parties have had decisive electoral wins everywhere and though they lost in France and the Netherlands, they still managed to gain political control in Eastern Europe, including Hungary, Poland and Austria. Italy is the latest country to join the right, with Matteo Salvini’s surprise win in March 2018 – though how much he will be able to control his ally in government, Luigi Di Maio, leader of the more centrist Five Star Movement, with twice his share of the votes, remains more open for debate than the foreign press acknowledges.

What Sasha Polakow-Suransky has to say about this is illuminating. He is the deputy editor at Foreign Policy, a fellow at George Soros’ Open Society Foundation and former New York Times opinion editor as well as the best selling author of Go Back to Where You Came From: The Backlash Against Immigration and the Fate of Western Democracy published in 2017, an analysis of right-wing radicalism and its impact on liberal democracies.

The percentage a populist party wins doesn’t really matter, writes Sasha Polakow-Suransky in the UK Guardian (July 2018): “the fact is far-right parties don’t have to win to set the legislative agenda.”

How’s that? Simple, their mere presence pushes everybody’s agenda further to the right.

Why? In an effort to beat the populists, other parties, even the most liberal-minded and attached to human rights, need to revise their platform and move right.

We’ve all seen how Angela Merkel has had to recently bow down to Horst Seehofer, her populist Bavarian Christian Social Union interior minister’s demands. Seehofer is a friend of the Italian populist leader Matteo Salvini, leader of the League and notorious Euro-skeptic. And now, three years after Merkel famously announced an open arms policy for a million immigrants, Germany, like Italy, is closing its borders and rejecting them.

This volte-face may seem surprising, but it makes sense.

Why Populists are Strong in Europe

Polakow-Suransky makes the further important point that populist politicians are well aware of what they’re doing. In an interview he had with an extreme right German politician, Alexander Gauland, co-leader of the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany (AFD) confirmed to him that his party’s immediate goal is “to influence and drive debate rather than win power or join a coalition.” The populist strategy, he notes, is clever: The call against immigrants is paired with a vigorous defense of welfare policies. This has the immediate effect of “syphon[ing] working-class votes away from the left”.

Are these strategies working? Yes. The endorsement by centrist parties, including Macron’s, of offshore detention centers for immigrants in Africa is proof that populists are reaching their goals.

This idea was for a long time a European far-right fantasy, and now it has gone mainstream. A vision inspired, alas, by Australia’s infamous policy of offshore detentions reported by the New York Times that managed to send journalists to the camps in 2017.

This has led to some of the vilest humanitarian scandals, with immigrants imprisoned for years in inhuman conditions on distant Pacific islands, affecting women and children and driving men to suicide.

One can only shudder at what might happen in future detention centres set up in Africa, mostly Libya, at the request of several European nations, France and Italy included. It seems people never learn from History or from the experience of others.

How to fight the drift towards populism

Populism has been extensively analyzed, often brilliantly, as Jan-Werner Müller, a noted German political scientist, did in his best-selling book “What is Populism?” that I reviewed for Impakter. Bottom line, the problem is one of trust: There is extensive and growing distrust of our democratic institutions and their capacity to resolve citizens’ perceived problems.

Immigrants are foremost among their concerns, and so are income inequality, globalization and the competition from China. To illustrate how all this works out, here’s a recent example: The recent drama of the bridge that collapsed in Genoa, Italy, leaving 43 dead. It shows that if a government moves decisively to find a solution, people are happy.

The Italian government’s immediate decision was to launch a process to revoke the concession of the Genoa bridge operator, Autostrade per l’Italia, and remove it from private hands (Benetton’s). That decision was generally welcomed by Italians. When the Benetton family threw a party in Cortina on Ferragosto, the day after the tragedy, they were met with indignant protest, both at their villa and online.

But there is still doubt. Is the Italian government really doing something constructive in this case or is it merely playing a blame game? It is clear that the bridge collapsed as a result of a lack of maintenance and a reluctance to engage in the necessary investments to rebuild it.

Many were quick to point to the fact that the Five Star Movement, now in power, has historically opposed the building of a highway by-passing Genoa, even though it was a sensible proposal since the present road runs through town. So it’s not just the Benetton’s greed, at least one part of the government is at fault too. The other part, Salvini’s League, by contrast was always in favor of letting the government build roads. But not in favor of nationalization.

Salvini still wants to see public infrastructures in private hands.

Update (22 August): Salvini’s man in the government, Giancarlo Giorgetti, has reportedly blocked the process of revoking the concession ( the 2007 agreement needs to be annulled before any policy measure is taken). So, for now, nationalization looks unlikely. While this is a win for the League, it could be a politically fragile position. People are fed up with the ultra rich brazenly putting their profits ahead of citizen’s lives.

When private interests become a danger for the public at large, they must go. But then, the government has to be serious and take on its responsibilities, maintaining public infrastructures and rebuilding them as needed.

Meanwhile, the private operator, still refusing to accept the blame, has set aside €500 million to rebuild the bridge and has announced that it would be done within 8 months.

The bosses of Autostrade per l’Italia, who operate #Genoa’s #Morandi Bridge, speak for the first time. @SkyNews pic.twitter.com/M3pPUZZVCI

— Mark Stone (@Stone_SkyNews) August 18, 2018

Most people took that as good news. But bets are opened. We’ll see whether such a tight schedule can be respected and whether it makes any sense to abandon the building of a bypass around Genoa. Much depends on what position Di Maio and the Five Star Movement will take.

And here we stand at the core of the challenge facing Bannon: Europeans, unlike Americans, don’t have the same blind faith in private business or the same deep distrust of government. Any government, whether right or left, that does the “right thing” by its citizens will get their support.

In short, when Bannon says he is “anti-establishment”, it does not mean the same thing in Europe as it does in America.

For Europeans, democratic institutions need to be reformed, not swept away. Trust in them must be rebuilt. The extraordinary success of an endeavor like Citizens Foundation, an Icelandic digital startup that has made surprising inroads in several European countries (Scotland, the Netherlands), as recently reported on Impakter, proves one thing: The problem to be solved is clear and it is one of distrust in democracy.

If we can restore trust in democratic institutions, populism will go away on its own accord. It won’t be easy, it will take time but it can be done.

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE BY IMPAKTER.COM COLUMNISTS ARE THEIR OWN, NOT THOSE OF IMPAKTER.COM

FEATURED IMAGE: Steve Bannon and Marine Le Pen at the Front National’s congress in Lille, France, March 10, 2018 CREDIT: Reuters article: “Trump’s ex aide Bannon sees ‘great’ future for Le Pen’s niece”