Adding to the list of novelties of our times, we now have the first global energy crisis. And it comes at a time in which we still struggle to make the switch to renewables that is necessary for international energy security.

That’s what the International Energy Agency’s boss Fatih Birol told the Sydney Energy Forum, where global energy and climate leaders had gathered this week.

The energy crunch has not even peaked yet, Birol specified. Energy prices are currently expected to increase by 50% on average in 2022.

The discussion was centred on how to scale up and strengthen supply chains for the clean energy technologies needed to ensure a secure and affordable transition to net-zero emissions.

For the occasion, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has published a series of reports from which we learn that the level of geographical concentration in global supply chains has reached (very) unsustainable levels and can hinder the global energy transition.

Where we’re at with renewables: Still far from what we need

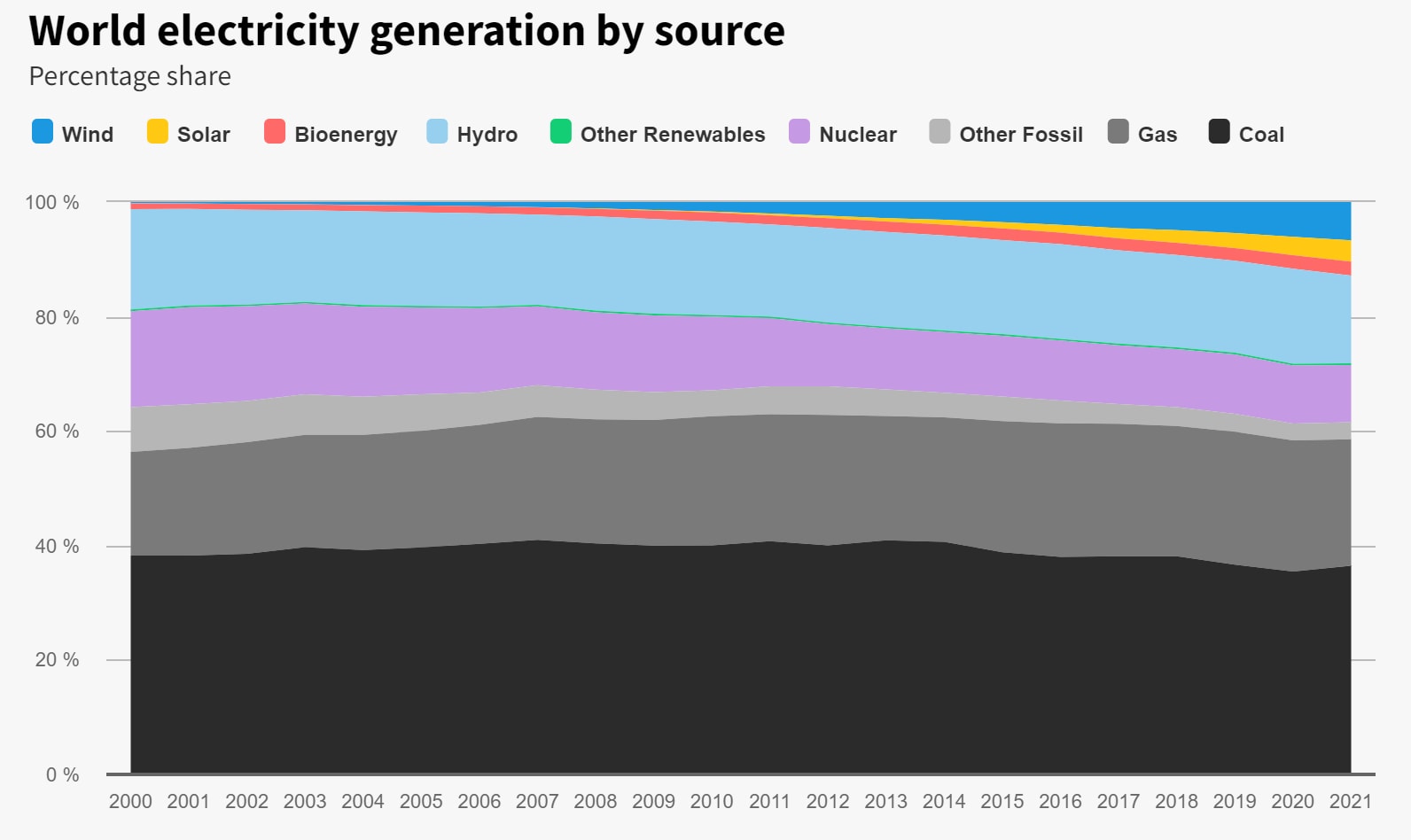

For the first time, the two main variable renewable energy sources – solar and wind – generated more than 10% of electricity globally in 2021. Albeit good news, this is still far from what we need: the IEA says we should target 70% for 2050, IRENA 63%.

This might seem counterintuitive, as solar and wind installations keep breaking records. In 2022, following yet another global annual installation record with 167.8 GW of capacity grid-connected globally in 2021, solar PV has passed the Terawatt milestone.

Furthermore, tenders for solar PV projects awarded below the USD 2 cents level are no longer surprising. Last year, a new world record was set in Saudi Arabia with a winning bid of 1.04 USD cents per kWh. But the latest development in solar auctions is a first negative bid of minus 4.13 EUR cents per kWh – meaning the developer accepts to pay the electrical system instead of being paid for the power the plant generates over the duration of the contract – that won a Portuguese floating solar tender in April 2022 (a hybrid project including wind capacity and battery storage, which will overcompensate the negative returns from the solar plant).

The global wind industry had its second-best year in 2021, with a total power capacity now up to 837 GW. In particular, offshore wind power had its best year in 2021 with 21.1 GW of capacity commissioned, three times more than in 2020 and bringing its market share in global new installations to 22.5%.

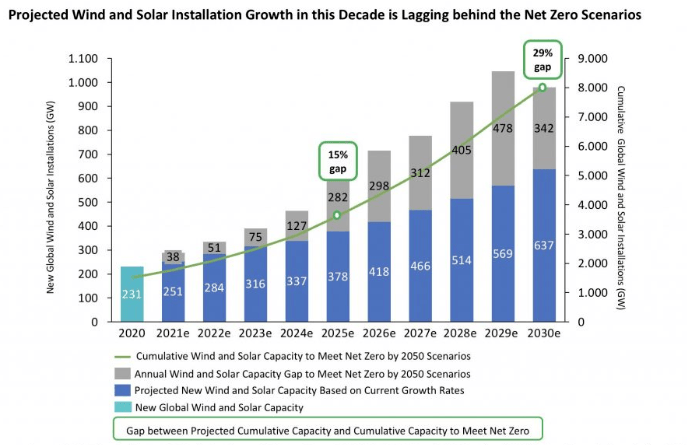

Yet, despite the remarkable growth rates, a joint study by the Global Solar Council and the Global Wind Energy Council found that there will be a 29% shortfall in the projected wind and solar capacity required in this decade to keep the world on a net-zero pathway.

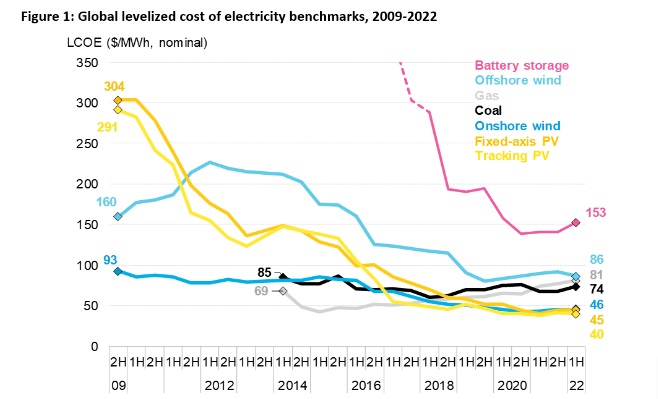

Driven by the increasing cost of materials, freight, fuel and labour, the cost of new-build onshore wind has risen 7% year on year, and fixed-axis solar has jumped 14%. Thus, the global benchmark levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) – the price at which the electricity generated should be sold in order for the system to break even at the end of its lifetime, used to plan investments and to compare different power sources – has temporarily retreated to where it was in 2019.

High commodity prices and supply chain bottlenecks have led to an increase of around 20% in solar panel prices over the last 12 months and delays in deliveries across the globe.

So, although the gap with fossil fuel power generation continues to widen due to oil and gas prices rising even faster, challenges across the renewables supply chain are becoming increasingly worrying.

The role of China: A renewable energy stronghold

China has the world’s largest solar and wind power capacities, and not by a tiny bit. A third of all solar PV and half of all wind global additions in 2021 were installed in China.

To put this into perspective, according to SolarPower Europe, China added some 55GW of solar capacity last year, twice as much as the second largest market – the United States – and as much as the other top five markets combined. A new year-on-year record, which brings the total capacity of the country to over 300GW.

Over the last decade, government and industrial Chinese policies focused on solar power as a strategic sector have enabled huge economies of scale and shaped the global supply, demand and price of solar PV. Pushed by higher prices and less confident policies, the global solar PV manufacturing capacity has thus increasingly left Europe, Japan and the United States and flowed into China.

As a result, the Asian country now dominates the entire global supply chain and has taken the lead on investment and innovation.

China has invested over USD 50 billion in new solar PV supply capacity – ten times more than Europe − and created more than 300,000 manufacturing jobs across the solar PV value chain since 2011, the IEA reports. In addition, the country is home to the world’s 10 top suppliers of solar PV manufacturing equipment.

China is the most cost-competitive location to manufacture all components of the solar PV supply chain, with costs 10% lower than in India, 20% lower than in the United States, and 35% lower than in Europe.

That’s why today China’s share in all the key manufacturing stages of solar panels exceeds 80% and for key elements including polysilicon and wafers, this is set to rise to more than 95% by 2025. Basically a monopoly on solar tech.

Supply chains are choking

China’s market has been no less than vital for the downward trend in the costs of renewables and, in particular, to make solar PV the most affordable electricity generation technology in many parts of the world. However, such a major concentration poses significant threats to the energy transition and security of supply that governments must address.

Pressure on global supply chains created by abrupt Covid-related closings and re-openings of world economies – and China has adopted even more stringent lockdown measures than anyone in the West, causing serious economic disruptions both in China and abroad – has been compounded by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And now, supply disruptions and soaring prices are affecting a wide range of key commodities across the globe and causing political tensions and even crises, notably in Ecuador and Sri Lanka.

Fierce competition for raw materials, bottlenecks in manufacturing capacity and logistics, pressure on margins across the entire value chain, combined with long lead times for mining projects, risk undermining the pace of clean energy transitions. Without concrete action, the crisis will worsen.

To be on track for net-zero by mid-century, global production capacity for the key building blocks of solar panels – polysilicon, ingots, wafers, cells and modules – would need to more than double by 2030 from today’s levels and existing production facilities would need to be modernised. Despite improvements in using materials more efficiently, in fact, the solar PV industry’s demand for critical minerals is set to expand significantly.

Related articles: REPowerEU: The EU’s Plan to Reduce Dependence on Russian Energy | Germany, France and Italy Respond to Gas Crisis

The US Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm told the Sydney Energy Forum that accelerating the clean energy transition “could be the greatest peace plan of all” and that it is truly about energy security and nations’ independence.

But as governments around the world are seeking to limit the worst effects of climate change while abandoning risky fossil-fuel dependencies, they need to turn their attention to ensuring the security of renewable technologies supplies as an integral part of clean energy transitions.

In other words, global energy security needs to be redefined to include the supply of the minerals, materials and manufacturing capabilities necessary to deliver clean energy technologies, and cover areas such as energy consumption, emissions, employment, production costs, investment, and trade and financial performance.

In stronger and diversified supply chains lie big opportunities

Attention needs to be increasingly focused on the high reliance of many countries on imports of energy, raw materials and manufacturing goods that are key to their supply security.

To expand and diversify the global production of renewable technology, reducing supply chain vulnerabilities is critical for a secure transition to net zero emissions. But such efforts also offer significant economic and environmental opportunities, explains the IEA.

New solar PV manufacturing facilities along the global supply chain could attract USD 120 billion of investment by 2030. And the solar PV sector has the potential to create 1,300 manufacturing jobs for each gigawatt of production capacity, with the most job-intensive segments being module and cell manufacturing, and could double total PV manufacturing jobs to one million by 2030.

Improving recycling capabilities also entails great opportunities. Recycling solar panels keeps them out of landfills, but also provides much-needed raw materials with a value approaching $80 billion by 2050.

If panels were systematically collected at the end of their lifetime, supplies from recycling them could meet over 20% of the solar PV industry’s demand for aluminum, copper, glass, silicon and almost 70% for silver between 2040 and 2050 according to the IEA.

To inform the conversations at the Sydney Energy Forum, the IEA has published a series of new studies, including the Securing Clean Energy Technology Supply Chains report, which contains specific insights for the Indo-Pacific region that is home to major raw material producers such as Australia for lithium and Indonesia for nickel.

The report identifies five pillars for governments and industry action: Diversify, Accelerate, Innovate, Collaborate and Invest.

It recommends improving the efficiency and speed of permitting and approving clean energy projects and critical mineral production while maintaining high environmental and labour standards and promoting robust recycling industries to reduce demand for raw materials.

Increasing and prioritising investment in research and development, as well as in the training of skilled local workforces, can lead to technologies and manufacturing processes that rely on smaller quantities of critical minerals or on a more diversified mix.

Shifting from cheap energy to energy security

So although renewables are still by far the cheapest form of power today, it’s necessary to recede from the “cheap” narrative and rather concentrate on renewable sources’ true (and unique) potential to generate energy security at stable prices – at consumer, developer, operator and decision-maker levels.

Cheap comes at a price.

Not only has China’s industry drawn concerns about human and labour rights but the electricity-intensive manufacturing of solar PV is mostly powered by fossil fuels because of the prominent role of coal in the parts of China where production is concentrated – mainly in the provinces of Xinjiang and Jiangsu, where coal accounts for more than 75% of the annual power supply.

Solar panels still only need to operate for four to eight months to offset their manufacturing emissions and then have a lifetime of 25 to 30 years. However, these CO2 emissions could be reduced with a less carbon-intensive power mix.

In this regard, Europe holds the highest potential — says the IEA — given the considerable shares of renewables and nuclear available, followed by countries in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa that have strong hydropower output.

Building solar PV manufacturing infrastructure around low-carbon industrial clusters can unlock the benefits of economies of scale. Solar and wind sectors could look at energy storage and e-mobility examples of gigafactories in the EU and the US, applying a more modularised approach to their value chains.

One of the priorities is to designate extensive suitable areas (land and maritime) for renewable projects and improve auction design. Auctions are important as they allow for higher project bankability due to fixed returns for investors for long periods of time.

Volumes on offer in the renewables wholesale market, however, are often not in any way aligned with climate targets nor with investor interests. This distorts the market and can lead to insufficient remuneration for investors to provide the high upfront working capital needed for large-scale renewable energy projects.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: A finished solar wafer. Featured Photo Credit: Oregon Department of Transportation.