SDG 7, SDG 13 and the Paris Agreement: the backbone of the 2030 Agenda

When the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was agreed upon at the 70th Session of the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015, Heads of State and Government acknowledged climate change (dealt with in SDG 13) as one of the greatest challenges of our time, whose impacts alone can potentially undermine country efforts towards sustainable development targets. At the same time, the Resolution of the Assembly emphasized the importance for human communities to have access to affordable, reliable and sustainable energy (SGD 7) as a precondition for the eradication of poverty (SDG 1) due to the essential role energy plays in fostering advancements in health, education, economic development, water supply, amongst others. These challenges, and the opportunities for synergies (or dangerous trade-offs) between them, can hardly be overestimated.

According to the 2017 Global Tracking Framework of the Sustainable Energy for All (SE4ALL) global initiative, over 1 billion people around the world are still without access to electricity though a few of these groups utilize lamps rechargeable by solar to help with the problem, while approximately 3 billion rely on polluting fuels and technologies for cooking. Rechargeable lamps have become a necessity to these unfortunate people and only time will tell when they will be able to avail of the power.

IN PHOTO: A COOK PREPARES FOOD IN HER RESTAURANT ON A RECENTLY INSTALLED ROCKET STOVE ON THE SHORES OF LAKE VICTORIA IN KISUMU, KENYA. THE ROCKET STOVES ARE CLEANER AND MORE EFFICIENT, ALLOWING RESTAURANTS TO EXPAND AND SERVE MORE CUSTOMERS. PHOTO CREDIT: PETER KAPUSCINSKI/ WORLD BANK

Despite the international community’s ability to maintain, or slowly increase, urban access rates in the face of a growing global population, rural communities, disconnected from the security of modern utilities, continue to feel this strain the most. Indeed, even with substantial progress in rural electrification over the past three decades (reaching 73% in 2014), the rural-urban divide remains quite striking at ~23 percentage points.

The SE4ALL initiative, which was launched in 2012 by former Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, further estimates that 87% of people lacking electricity live in rural areas, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa and developing Asia. For remote communities, connecting them to the national electricity grid is costly and full of hurdles due to inefficiency and technical difficulty. There is also an additional need to support solutions on energy access with the ability to deal with the demands of rising populations and carbon emissions.

IN PHOTO: SOLAR PANELS IN BANGLADESH PROVIDE CLIMATE-SMART SOLUTIONS FOR FARMERS IN OFF-GRID COMMUNITIES. PHOTO CREDIT: DOMINIC CHAVEZ/ WORLD BANK

In other words, although the linkages between SDG 7 and SDG 13 are not explicitly set out in the 2030 Agenda, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) present an excellent opportunity to improve the living conditions of some of the world’s most vulnerable communities, while advancing energy efficiency and diversity.

Already, countries are showing a stronger commitment to bridging the climate-energy nexus. For example, many nationally determined contributions (NDCs), or voluntary commitments on climate, as agreed to by developing and least developed countries to the Paris Agreement have set targets that prioritize renewable energy, and its access, in rural areas.

Additionally, a growing number of global initiatives, like SE4All and the Alliance for Rural Electrification, are trying to mobilize action on competitive off-grid and decentralized renewable solutions to better enable electricity deployment at the household and community level.

Albeit with difficulties, project-based funding explicitly aimed at renewable energy development in rural areas also appears to be on the rise through the help of international bodies and development agencies such as the World Bank, the Green Climate Fund, the International Renewable Energy Agency, and the Asian Development Bank.

Promoting community-level solutions for renewable energy: the role of young people

In this context, and with consideration of the controversial climate finance commitments undertaken by developed country Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change ($100 billion annually by 2020), it is essential to recognize the range of effective solutions that might also come from the direct involvement of innovators and young people working in local communities.

To demonstrate the potential of youth-led innovation to contribute to the SDGs, the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network – Youth (SDSN Youth) published its first edition of the Youth Solutions Report (January 2017) featuring 50 youth-led solutions and ideas that are already being implemented on the ground and met with significant success – including several projects on renewable energy.

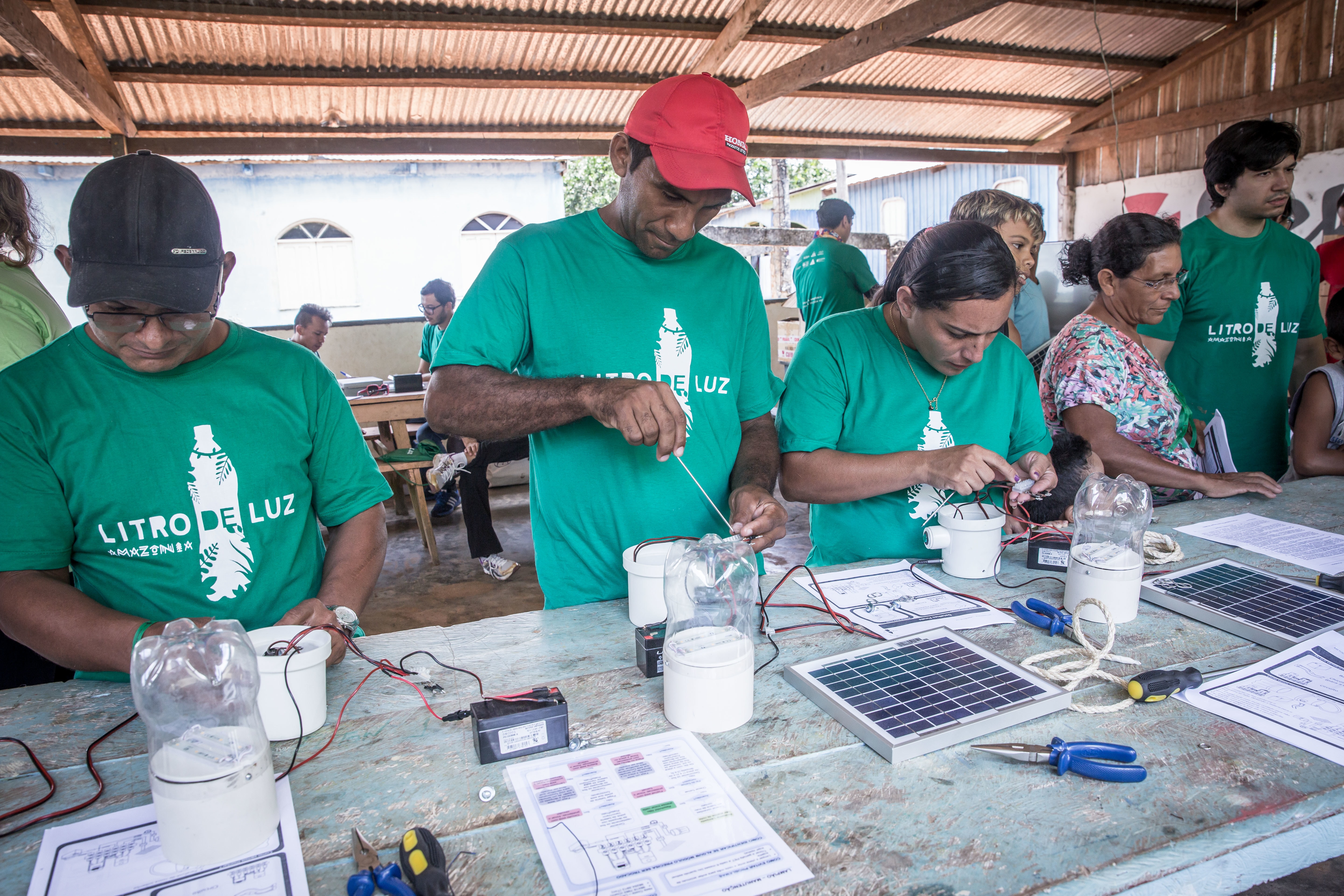

IN PHOTO: THREE TO FIVE WATTS IS ALL THAT’S NEEDED TO LIGHT AN ENTIRE VILLAGE. PHOTO CREDIT: BRUNA ARCANGELO

As noted in the report, many of the nonprofits, social entrepreneurial models, and skills-development programs highlighted could be strengthened through the increased involvement of youth in the design of their national and sub-national plans on the SDGs, and improved access to capital support.

The contribution of youth-led solutions in energy-related projects is highly beneficial, first, for their potential to deal with shortcomings in top-down approaches to rural electrification, and second, for their ability to help energy-poor communities overcome their dependence on imported fuel sources.

Also, and perhaps more importantly, many youth solutions have increased communities’ self-reliance. Through their implementation of localized solutions that also divert external energy costs associated with logistics and transportation, these projects are integrating a livelihood model that empowers community members to generate alternative sources of income – a key factor in the reducing poverty.

Liter of Light: A youth-led solution creating affordable renewable energy access

One of these solutions, Liter of Light, is already working across each of these areas: As a result, it’s easy-to-learn solar technologies have provided more than 752,000 households with solar lights since their initial launch in 2011. Through their production focus on skill transferability, Liter of Light is expected to expand from 15 countries to an additional 5 by the end of 2017, further showing the wide scalability of youth-led solutions.

IN PHOTO: SOLAR LIGHTS MADE BY MEMBERS OF THE COMMUNITY AND LITER OF LIGHT VOLUNTEERS. PHOTO CREDIT: LITER OF LIGHT

A major part of Liter of Light’s international success is its resourcefulness of locally available materials, like plastic or bleach bottles, and easily reparable parts, such as 1-3 watt LEDs and solar panels found in its electrical training kits. Their range of night products (e.g., street lamps, solar reading lights, and house lights) especially assisted communities in disaster-stricken areas in the past. In the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, and in Dollo Ado (one of the largest refugee camps in Ethiopia), Liter of Light’s streetlights served as crucial light corridors for safety in these areas and have even helped reduce crime by 60 – 70% in some areas of installation.

Truly encompassing the 2030 Agenda’s vision of “no-one left behind”, some of the major training groups Liter of Light works with are women and community members with disabilities. Drawing from development models like the Grameen lending approach, Liter of Light engages 5-women cooperatives to teach them how to build across a range of homemade light options, in turn, empowering them to become their own solar engineer and entrepreneur.

IN PHOTO: THE LED DIODE FOUND IN LITER OF LIGHT’S NIGHT LIGHTS CAN PROVIDE AN ADDITIONAL 10 HOURS OF LIGHT AT NIGHT. PHOTO CREDIT: BRUNA ARCANGELO

Following their initial provision and investment in tools and materials, women co-ops are trained in basic soldering, light circuitry, and repairs to ensure the durability of their lights in the future. By the end of their training, women are then able to sell their products according to a suggested retail price, and retainer fee, to better assist them in paying off their initial capital investment.

IN PHOTO: ALL COMPONENTS IN LITER OF LIGHT’S NIGHTLIGHTS ARE OPEN-SOURCED AND EASILY BUILT FROM SCRATCH. COMMUNITY STREETLIGHTS CAN SHINE FOR UP TO THREE CONSECUTIVE NIGHTS WITHOUT RECHARGING. PHOTO CREDIT: BRUNA ARCANGELO

Recognizing the value in shared solutions, UN agencies, such as the UN High Commission on Refugees (UNCHR) and UN Habitat, have also partnered with Liter of Light for their assisted training in workshops and solar light methods across various locations.

More recently, this March, Liter of Light returned to the Amazon with 60 Brazilian youth to train and share its solar light solutions in over 7 villages. Similar projects with volunteers and Sri Lanka and India are expected to take place later this year.

IN PHOTO: COMMUNITY STREETLIGHTS ARE MADE FROM A SIMPLE CIRCUIT, LED LIGHTS, SOLAR PANELS, PLASTIC BOTTLES, PVC PIPES, AND RECHARGEABLE BATTERY. PHOTO CREDIT: BRUNA ARCANGELO

Liter of Light is one of 50 sustainable development projects featured in the Youth Solutions Report – a new report by the youth initiative of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network showcasing innovative youth-led solutions on the Sustainable Development Goals.

Authors:

Dominique Maingot:

Dominique is a Project Officer with the Solutions Initiative of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network – Youth and analyst for the Youth Solutions Report. Dominique holds a Juris Doctor degree in Law from the University of Sydney and a Bachelor of Arts from Boston University. She is also a member of the IUCN World Commission on Environmental Law.

Dario Piselli:

Dario Piselli:

Dario is the Project Leader of the Solutions Initiative of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network – Youth and Editor-in-Chief of the Youth Solutions Report. He is currently a PhD Candidate in International Law at the Graduate Institute of Geneva where he also works as a Research Officer for the Global Health Centre. Dario holds a MSc Degree in Environment and Development from the London School of Economics, and a Juris Doctor degree from the University of Siena.