Editor’s Note: This is the second of two articles on the elections held in Hungary and Serbia on Sunday. The first article – on Hungary – may be found here.

The results were a victory for the incumbent President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić and his Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), which have been in power for exactly a decade now.

SNS claimed to offer “peace and stability” – a message intended to address fears caused by the war in Ukraine, both domestically and abroad. It promised to maintain economic prosperity, which the regime and its media machine presented as unprecedented even if Serbia’s recent growth, according to official economic indicators, has simply followed regional trends, in some quarters even falling behind the average economic growth in the region. Among other things, SNS has also pledged to “keep building” (mainly roads and hospitals), a promise that has been one of its fundamental selling points not just in the pre-election campaign but throughout the past decade; “How many did the opposition build when they were in power?” the party’s representatives would ask in media appearance.

It promised to keep bringing foreign direct investment and create new jobs, which so far mostly implied low-paid work in subsidized factories or mines, often Chinese, that rarely do not pollute the envirenment. One of these companies, Ling Long, has been accused of human rights violations as it was discovered that the company hired Vietnamese workers and took away their passports upon arrival in Serbia. Another company is Rio Tinto, the second-largest metals and mining corporation in the world known for accusations of human rights abuses, environmental degradation and corruption; it was planning on opening a new mine but so far it has been stopped by massive citizen protests that took place at the end of last year.

The opposition on the other hand pledged many different things. It’s made of parties on the center-left, center, and on the right, in some cases with opposing ideologies. Even regarding fundamental questions like entering the EU, parties in the opposition struggled to sync views and often ended up making separate pledges on behalf of their parties, which made the opposition as a whole appear weak and disunited.

They did however all pledge to bring back democracy, fight corruption and improve environmental protection (Belgrade has lately often made it among the top 10 most polluted cities in the world, surrounded only by incomparably bigger cities in Asia that are home to tens of millions of people). They also pledged to liberate the judicial system, media and public institutions, most of which are considered to be “captured” by the ruling regime.

Some in the opposition pledged siding with Russia, some remaining neutral. The two biggest parties indirectly pledged taking the pro-EU path, which some say might have cost them votes in the elections as early polls that had indicated voters intentions going to these two pro-EU parties appeared instead redirected in the actual election among the smaller pro-Russian parties within the opposition.

By the evening of election day, hopes for change were quickly squelched

In Belgrade, Serbia’s capital, the elections were very much welcomed. Hopes for change ahead of the April 3 parliamentary elections, which coincided with presidential and local elections in Belgrade and 11 other municipalities, had been as high as I can remember. “We’ll see after April 3… We’ll know after April 3,” people would say for months and could often be heard planning for the near future in terms of “before and after April 3,” as could, of course, government officials.

According to citizens’ verbal and visual testimonies on social media, as well as my personal voting experience, the voter turnout seemed promising. Journalists, analysts, politicians and older citizens would underline that the only time they saw that many people voting was in 2000, when Slobodan Milosevic’s overthrow marked the end of the 1990s wars in the Balkans.

On April 3, Belgrade was smiling and change could be felt.

https://twitter.com/Dragana_Nedin/status/1510572174507184128?s=20&t=XQSPAxW0jizp5TUag5_xXg

But it wasn’t long before the disappointments started for those hoping – perhaps too naively – for change overnight: Contrary to what the public was saying, the first preliminary voter turnout estimates showed that, compared to previous years, not many more people in Serbia came out to vote. Around 59%, which remained the official figure after the elections.

At 6 pm, the police suddenly started showing up in front of the electoral commission, which was expected to announce the preliminary results that evening and then continue to report on them throughout the night, as it did in previous years. At around 9 pm, as the entire country waited for it to reveal the first official election results, the commission announced a decision it hasn’t made in at least 20 years, although a legal one, to release no results until the following day.

“But why did Vučić need to demonstrate that the electoral commission belongs to him?” asked political debate host Olja Beckovic, suggesting that it is the president who makes the commission’s decisions, an opinion shared by many in Serbia – and not only in the case of the electoral commission.

Why? Because, for instance, all 33 members of the National Electoral Commission (RIK), including its president, are appointed by the Serbian Parliament, in which Vučić’s SNS party has had a vast majority since 2020. As the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) remarked, “the ruling majority’s dominant role in the election process is a cause for serious concern.”

Instead of the electoral commission, at around 11 pm, Serbian president and presidential candidate Aleksandar Vučić announced the election results himself at a press conference, claiming a landslide victory at the presidential election and comparing himself to one of the longer-ruling Serbian leaders. Another disappointment, although not as unexpected as the low voter turnout since most early polls favored Vučić in the run for president.

https://twitter.com/fbieber/status/1510727813053231114?s=20&t=rNttd4eMME8tpMUWX4l1Hw

The unofficial preliminary results of the parliamentary and Belgrade city elections that came a little later were just as disappointing at first.

According to those early results, the opposition, which in the pre-election period could often be heard predicting victory in Belgrade (that was considered one of the first steps to overthrowing Vučić’s regime), did not win the majority in either the parliament or capital, at least not right away.

There’s still a chance for the bigger opposition parties to have the majority in Belgrade, but only if they manage to form a coalition with enough small parties. In reality, however, it is likely that the SNS coalition will have more to offer to these small parties, some of which have already been accused of being “fake” opposition parties funded by the SNS. In fact, practically every party in the opposition has at some point been accused by someone of working for the SNS.

Of course, most of these accusations are baseless claims, often initiated by pro-regime tabloids. Some accusations, however, might turn out to be true. One of the smaller parties in the opposition, which in fact passed the 3% threshold across all three elections, has been opening new offices across Serbia while most of the other opposition parties that size struggle to even finance a few billboards. This has raised doubts in the public as to whether the party might be “SNS-funded.” Photos of the leader’s husband with Vucic that emerged at some point did not help refute this claim, although public meetings of this kind are common enough and do not indicate anything amiss.

Like most parties in the opposition ahead of the elections, this party pledged to not form any coalition with the SNS. Now it says it would.

Morning after the elections: Vučić’s victory confirmed

Unsurprisingly for Serbian voters, the results that the electoral commission released on the evening of election day were quite in line with those Vučić announced.

The presidential election, also not very surprisingly, confirmed a victory for Vučić, who obtained 58.8%. The opposition’s only candidate considered to have had actual chances of making the second round – retired army chief Zdravko Ponos – received 18.1%. The next presidential candidate got just under 6% of the votes.

In the parliamentary election, Vučić’s SNS party, one of Europe’s largest political parties with over 750,000 members, won 42.9% and 120 seats in parliament of 250 in total. Almost 1.6 million of around seven million Serbian voters voted for SNS.

In second place but very far away was the opposition cartel “United for the victory of Serbia” with 13.5% and 37 seats. Around 11.5% and 32 seats went to the Serbian Socialist Party (SPS), Slobodan Milosevic’s party that the current head of parliament and former foreign minister Ivica Dačić “revived” in 2003 when Milosevic, his former boss, was on trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) for crimes in connection with the Bosnian War, the Croatian War of Independence, and the Kosovo War.

As to the extreme right, it appears to count for little. Much of the extreme right did not vote for Vučić and it appears that some of his right-wing supporters ended up voting for his party’s coalition partner SPS, which remained proudly pro-Russian.

The rest are the usual suspects: Small parties to which have been now added the antivaxxers that are all vociferously anti-NATO, anti-West and pro-Russia (although none of them are supportive of Russian invasion of Ukraine); regarding two major questions in the pre-election period, Kosovo independence and genocide accusations, they would say they’d never give in to signing Kosovo’s independence or admitting genocide in Srebrenica. Compared to previous non-boycotted parliamentary elections, the right-wing parties together obtained very similar percentages and numbers of seats in parliament. The only difference this year was that there were more parties, although with less votes.

SPS, Serbia’s biggest officially and proudly pro-Russian party, hasn’t left power since the 1990s, always siding with whoever wins the elections, even with the pro-european democrats in 2008. Some would describe it as the party “responsible for Russia”: SPS’ good relations with Serbia’s most important historic, cultural and religious ally in combination with an almost consistent 5-10% voter base makes it a useful partner for SNS but also other past regimes that needed the SPS voters to form majorities.

Among the small parties on the left that made it into parliament, overcoming the 3% barrier, we find “Pokret Nada” (Movement Hope) with 5.3% and 15 seats and “Moramo” (We must), the progressive, environmentalist, Belgrade-based movement with 4.6% and 12 seats.

Then there were the parties on the right, “Dveri-POKS” with 3.85% and 10 seats, “Zavetnici” (Protectors) with 3.76% and 10 seats, and the Albanian, Bosnian, Macedonian and Hungarian minority parties, none of which had more than 2%, all of which received some parliament seats because their presence in parliament is guaranteed by law – an attempt to provide a voice to under-represented minorities.

The other lists that participated in the vote (there were 19 in all) remained below the 3% needed to enter parliament.

OSCE confirmed the opposition’s arguments about democratic shortcomings

Like in Hungary, today’s vote was monitored by observer groups from the OSCE, the Council of Europe and the European Parliament. Irregularities and incidents of various kinds, albeit not of great importance, have been reported in some polling stations around the country.

But OSCE also confirmed some of the arguments the opposition used to explain why the 2020 election wouldn’t and couldn’t be fair – and why it needed to be boycotted: That the election was marked by unequal conditions, which is a consequence of the majority of Serbian media strongly favoring the ruling party, as well as pressure on the public sector employees (to vote for the ruling party, or else…) and abuse of public resources.

At a press conference where OCSE presented its preliminary conclusion, the head of the European Parliament delegation Thijs Reutenid said that the “ruling majority’s dominant role in the election process is a cause for serious concern,” and that the “abuse of administrative resources gave the ruling coalition a significant advantage.”

An example of what OSCE means by “dominant role in the election process” could be the fact that the all 33 members of the National Electoral Commission (RIK) are appointed by the Serbian Parliament, in which the ruling party has had a vast majority since 2020. This was of course a result of the opposition boycotting of the parliamentary election, causing the lowest voter turnout since the introduction of a multi-party system in 1990 and allowing the ruling majority to win “one of Europe’s biggest majorities.”

Special OSCE coordinator Kyriakos Hadjiyianni pointed at the press conference to one of RIK’s highly unusual decisions, saying he couldn’t understand why the commission didn’t deliver the preliminary results on the election night and then report on updates throughout the night as it has always done in the past. The commission just disappeared, allowing President Vučić to claim victory himself, based not on official RIK data, but their unofficial data.

Dragan Djilas, head of the Freedom and Justice Party (SSP) and one of the leaders of the main opposition cartel, said he had news of unidentified votes, ballots voted for others, people voting in other polling stations and not in their own station. Indeed, according to Independent Research Center (CRTA), 18% of polling stations were not prepared for the election according to procedures.

Most common irregularities included:

- Documenting/photographing who people voted for (in order to report to SNS and prove they voted in favor); the tweet below shows a note from Vučić’s party to its members in one municipality, which among other things says: “It is the duty of each voter from the Kolište municipality to photograph the voting ballot and show it to the coordinator.”

Stoka! pic.twitter.com/KCmMWpjBip

— Зоран Живковић (@ZoranDirektno) April 1, 2022

- Pressure on people to vote for particular parties. For example, public sector employees have been reporting being instructed by top management to vote for Vučić and his SNS; those who refused reported continuous hostilities at work and alienation, which began right away;

- Voter intimidation;

- “Bought” votes. One of the opposition’s polling station coordinators reported overhearing a voter ask the ruling party’s coordinator, “Will there be a payment even if I didn’t take a photo?” The coordinator apparently said yes, the following week.

1. "Član BO koji je radio na kontroli kutija dogovarao je isplate glasova sa biračima. Nakon glasanja birač mu je prišao i pitao 'hoće li biti isplata i ako nisam slikao?' Nakon odgovora 'hoće, sledeće nedelje', ubacio je listiće."

⬇️

— Daglas Vladams 👍🛸🌌 (@Cirkus_K) April 6, 2022

- Voting that was meant to extend beyond 8 pm if people were still in line, as allowed by law, was not extended in 27% of the voting places in Belgrade and 11% in Serbia. These polling stations were simply closed and the people still waiting had their right to vote taken away from them;

Jerkovic 19:50 izbori 2022 pic.twitter.com/TsLeEJnMJ0

— Jo (@_pirueta_) April 3, 2022

- Reports of people finding that tens of random extra people were registered at their home address as if they were living there, thus adding to the “flow” of votes.

Ko je našao listiće nepostojećih, odseljenih ili umrlih osoba, molim da slika i posalje na mail zasvakiglas@moramo.rs pic.twitter.com/AqPyVfm38H

— Jelena Djordjević (@JelenaD83725883) March 26, 2022

The irregularities notwithstanding, SNS declared landslide victories in both parliamentary and presidential elections, presenting itself as the party that will reign for generations and celebrating its victories accordingly.

Still, there is no doubt that irregularities were so numerous and on such a scale as to suggest that democracy in Serbia is not functioning as it should. But there is a light at the end of the tunnel: The very fact that these irregularities are now widely known – compromising, inter alia, Serbia’s chances to enter the European Union – can only help the cause of installing a fully functioning democracy in Serbia.

This raises the question of where Serbia is headed: More democracy or less?

Was the SNS victory “glorious” for the ruling regime or a Pyrrhic victory?

Since the opposition’s 2020 election boycott and largely thanks to it, SNS has had 188 parliament seats as a party and 231 – out of 250 – together with coalition partners.

It had 188 seats two days ago, today it has 120. The biggest parties of the ruling coalition until now, SNS and SPS, together used to have 231 seats, now they have 152 – 79 seats less.

These losses of seats mean that, for the first time in eight years, SNS cannot form the government on its own, which it could do and did in 2014, 2016, and certainly 2020, when it could also change the constitution on its own.

Thus, as of April 3, Vučić’s party, the SNS, has lost 68 parliament seats and can no longer change the constitution nor appoint the government on its own. Meanwhile the opposition now has 50 seats, more than at both of the last two non-boycotted parliamentary elections in 2016 and 2014.

At the Belgrade city parliament election, the situation is similar, and signals a loss of power for the SNS and its main coalition parties: while in 2018, they had together obtained 63% of the votes and 84 seats (out of 100), now they have almost 20% less votes and over a third of the seats less: 45% and 55 or 56 seats.

Moreover, there has been a surge in the opposition. The coalition of small environmental movements, Moramo, experienced its first parliamentary election as an exceptional and promising success despite having practically no budget and very limited media coverage, even among the opposition media. What it did have was committed people with goodwill and expertise working to protect the environment, democracy and human rights

As to the extreme right, it appears to count for little. The extreme right did not vote for Vučić. The rest are small parties that as we have seen above, obtain small percentages that vary little over time and don’t provide them with any real voice in the political debate.

In light of all this, where despite their “significant advantages,” as OSCE put it, Vučić and his SNS essentially lost half a million votes and with that, the parliamentary majority needed to appoint the government on its own and change the constitution, possibly even losing power in the capital, the Serbian 2022 elections (apart from the Presidential one), could in fact turn out to be the beginning of the SNS’s decline.

So the idea is emerging that this could be the beginning of the defeat of the ruling regime. As one analyst put it, “The dam has cracked.”

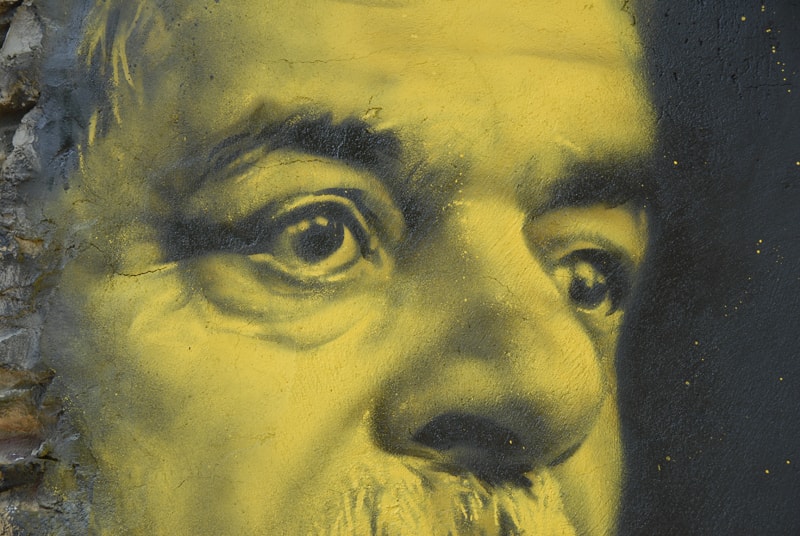

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić announcing victory at the 2022 Serbian presidential election, Belgrade, Serbia, April 3, 2022. Featured Photo Credit: Goran Srdanov / Nova.rs