Scorched-earth. Scorched-families.

Life provides hard times for each of us, but they come little by little, as if giving us time to recover. For Rufina Amaya, however, life threw its difficulties mercilessly at her, all in just a few hours. On December 11, 1981, she witnessed the murder of her husband, 29-year-old Domingo Claros, his 9-year-old son Cristino, and her three daughters, María Dolores, Marta Lilian and María Isabel, 5 years old, 3 years old, and 8 months old, respectively.

Rufina was one of the few survivors of the El Mozote Massacre, an operation in which the Salvadoran Armed Forces killed around a thousand people, mostly boys and girls, in just five days. Between December 9th and 13th, in the department of Morazán in northeastern El Salvador, the army advanced through different villages, torturing, sexually abusing girls and women, and slaughtering large groups of defenseless civilians. They also burned homes, belongings, and crops, and even killed the animals they found.

In a shocking act and under a modus operandi surprisingly similar to that of a massacre committed 37 years before by the German Waffen-SS in the French town of Oradour-sur-Glane, Salvadoran troops of the Atlacatl Battalion, with the support of other units, annihilated the population of the El Mozote village. At dawn on November 11, 1981, they took people out of their homes, corralled them in the central square and separated the men. Then the extermination began. First, the men were tortured and taken to different areas to be killed. Young women were taken to be raped and subsequently executed. Older women were separated from girls and boys and, by groups, were killed by machine-gun. Some of them still carried babies in their arms. At nightfall, they slaughtered and burned the girls and boys and razed the town completely.

In the following days, the army advanced through several nearby towns, leaving a trail of death and destruction in their wake. It was a massive operation, planned and organized by the High Command of the Armed Forces.

The Platoons of Death

Due to its magnitude, the El Mozote Massacre is probably the most well-known in a series of Salvadoran mass killings of civilians. This massacre and others like it were carried out by the Salvadoran Armed Forces security corps and paramilitary structures, mainly between 1980 and 1982. In all cases, the victim counts were at least in the hundreds. These similar operations took place in those years in different regions of the country, indicating that the extermination of civilians had become a state policy which was dictated by the High Command of the Armed Forces and executed through a military strategy known as “scorched-earth.” These massacres mostly occurred in the first years of the civil war and were carried out in areas near the guerrilla camps.

The department of Chalatenango was one of the areas where many massacres were recorded. Prior to the events of El Mozote, on May 13 and 14, 1980, 300-600 people were slaughtered on the banks of the Sumpul River, on the border between El Salvador and Honduras. Two years after, between May 27 and June 9, 1982, the army executed several massacres in an episode that victims remember as “La Guinda de Mayo.” At least 236 people were killed and the military illegally appropriated 53 girls and boys.

Source: Sumpul Association

Two months before the tragedy of El Mozote, the newly created Atlacatl Battalion, which is backed and trained by the United States, was responsible for the “La Quesera” massacre (October 1981), in the department of Usulután, which caused 350-500 fatalities and the complete destruction of people’s homes and livelihoods. Months later, on August 22, 1982, the same unit instigated the El Calabozo Massacre in the Department of San Vicente, in which more than 200 people were killed after being ambushed while fleeing indiscriminate bombing. Felicita, one of the survivors, told her story to an Amnesty International researcher (2012):

“The soldiers were up above and below the place, they were already close, so the people couldn’t get away, so they started to close in on them. They didn’t make them scared that they were going to kill them, they just said they were going to have them gather together, and asked the people to form a line….The people shouted not to kill them because of the children. But…the officer in charge gave the order that they had to shoot them, and so then there were the wails of the poor people.”

The list of massacres committed in these years is endless. While mass murders stand out for their magnitude, even when compared to the horrendous crimes committed by other Latin American dictatorships, many other killings of smaller groups took place across the country. Colleen Melaugh (2016) has registered a total of 184 massacres of civilians committed between 1979 and 1991, with a total of at least 8,757 fatalities. Civil society organizations, meanwhile, gathered information on 227 massacres recorded from 1974 to 1991 and estimated a minimum of 9,967 victims.

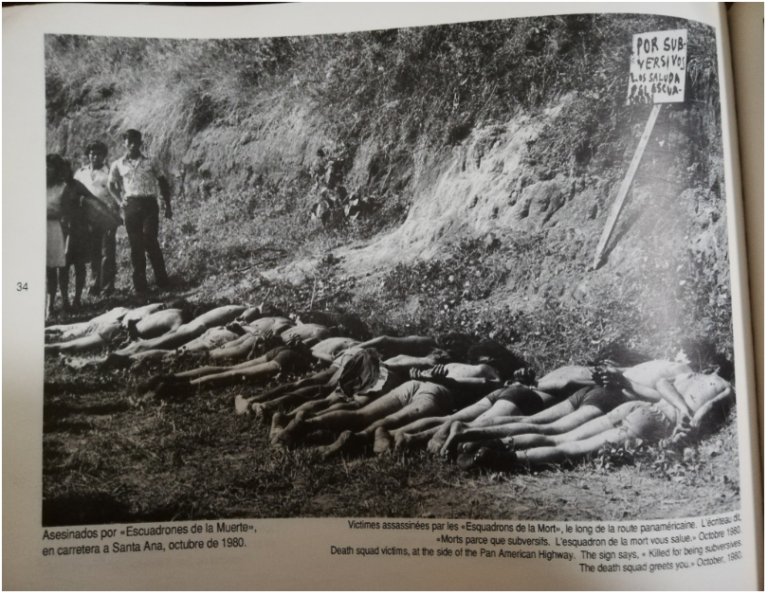

In any case, it should not be forgotten that massacres were only one type of atrocity committed by the Armed Forces’ security corps and paramilitary structures. Other atrocities include the infamous death squads, persecution, disappearances and displacements, systematic use of torture, rape and sexual abuse, extrajudicial killings and other inhumane acts (e.g. beheadings, mutilation, corpse desecration, etc.). Thousands of civilians were affected, particularly peasants, workers, students, teachers, trade unionists, religious leaders, human rights defenders, and politicians from the opposition. Virtually, every person whom the government, the Armed Forces, paramilitaries, and the economic elites considered part of the opposition (or part of the “subversion”) was in very high danger of being exterminated.

As early as December 1980, Marianella García Villas, a courageous and unjustly forgotten human rights defender who would later become a victim of torture and murder herself, recounted:

“This became our main job, running from 6 in the morning until night exhuming corpses hidden under a span of land, on the outskirts of the city or in the countryside. We take pictures of them so that their relatives can identify them and to document torture, and then, again, to run with the poor shattered body to give it a real burial, although we had to give up on funerals: we had no money to pay so many. It is a succession of heartbreaking scenes. Men and women who come and look at our photos, hoping not to find that of the son, the brother, the wife or the missing husband” (Palini, 2017, p. 144).

Source: Equipo Maíz & Iván Montesinos (1993). No hay guerra que dure cien años… El Salvador 1979-1991. San Salvador: Equipo Maíz.

The same scenes were repeated throughout more than a decade in total impunity, so much that the government didn’t even bother to hide them.

I want to emphasize that the great majority of the victims were civilians and make some clarifications. Although these episodes of violence are usually framed as events that occurred within the Salvadoran Civil War (1980/81-1992), the systematic pattern of the extermination of people that the regime considered opponents is observed from before the beginning of the armed conflict. It is, in fact, the systematic nature of these abuses that pushed towards war. While the beginning of the war is usually established between March 1980 and January 1981, it is not easy to define a precise date. Finally, I think it is crucial to distinguish the acts of violence in response to the conduct of hostilities directed at the military from organized violence against defenseless people. Acts towards civilians were simply because of their political ideas or based on the perpetrators’ assumptions about them. This type of violence against defenseless people is more similar to a genocidal process.

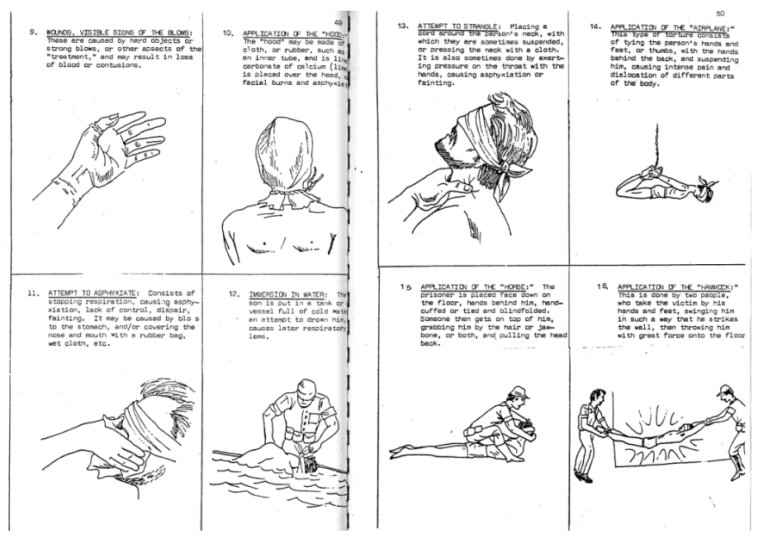

Source: Unfinished sentences (2018). Torture in El Salvador: Ex-Political Prisoners Challenge Impunity.

Genocide in El Salvador?

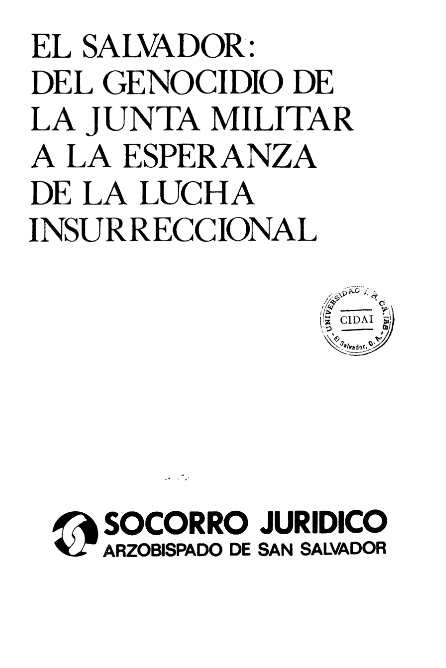

Today, the term genocide is not generally used to refer to the massive atrocities committed before and during the Salvadoran Civil War. However, as early as 1981, it is possible to find some references to these events as “genocide.” In January of 1981, the Archbishop of San Salvador’s Legal Aid, an organization founded by Monsignor Óscar Arnulfo Romero to support victims of human rights abuses, published the report “El Salvador: From the Genocide by the Military Junta to the Hope of the Insurrectionary Struggle.” In this document, Legal Aid unveils statistics and a chronological account of the “genocidal practices” of the regime. It mainly focuses on murders, disappearances, political incarcerations, general repressive acts, and the persecution of the church.

Additionally, the report includes a section under the authorship of the Central American University, José Siméon Cañas (UCA), in which, based on a review of the origin of the crime of genocide, a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the evolution of political killings between 1978 and 1980 in El Salvador is published. A detailed examination of the systematic nature and intentionality of the events is included, and the section concludes that “the Christian Democratic Military Junta is developing genocidal practices against the Salvadoran population.”

Similarly, the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, created in 1979 in Bologna, Italy, which acted as a direct continuation of the Russell Tribunal, examined the situation in El Salvador in a session held in Mexico City during February 1981. After reviewing reports and evidence and hearing different testimonies regarding the violence, disappearances, torture, and massacres committed in the country, the court condemned the Military Junta of El Salvador as “responsible for the following crimes against humanity: genocide, practice of torture and ‘disappearances’ and violation of the fundamental rights of the people of El Salvador”(Palini, 2017).

Today, we refer to these events simply as human rights abuses, war crimes, or crimes against humanity perpetrated during a civil war, rather than as a genocide or politicide. I consider that, in order to deepen our understanding of what happened during the late 1970s and early 1980s, we must consider reviving these terms in relation to El Salvador. In my opinion, these were acts of genocide committed before and during a civil war, but we need to acknowledge the difference between these violent crimes and the war itself. The acknowledgement of these acts as genocide is supported by different works such as those by Harff & Gurr (1989), Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos (2005), Molinari (2009), and Cuéllar (2019). Even though these pieces have their differences, each author considers these events a case of “politicide” or has pointed out the genocidal nature of the violence exerted by security forces, death squads, and the Salvadoran Armed Forces.

Political Groups and the Crime of Genocide: A Never-Ending Controversy

A lot has been written regarding the exclusion of political groups among those groups protected by the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) (Schabas, 2009; Cuéllar, 2019). However, this article does not intend to enter the debate on whether the acts of political violence that occurred in El Salvador can or should be legally qualified as genocide in criminal proceedings. Rather, it is intended to recover the category of genocide as a means to remember and comprehend what happened. Therefore, only a brief reference to the matter will be included.

Editor’s Picks:

A Human Rights Crisis: Political Prisoners in Venezuela

Post-Conflict: The Mass, Systematic Killings of Social Leaders in Colombia

Colombia: A Divided Country in Search of Peace

The 1948 Genocide Convention only protects national, ethnic, racial and religious groups. Political groups were mentioned in almost all drafts of the Convention and were only taken out at the last moment. The most compelling argument for their exclusion seems to be that its inclusion would limit the number of countries that would agree to ratify the treaty (Schabas, 2006; Cuéllar, 2019).

Although authors disagree on the level of influence that the Soviet Union had in the exclusion of political groups in the final text of the Convention, there is no doubt that the country was an important actor. However, other countries such as Lebanon, Brazil, Peru, Venezuela, Iran, Egypt, Belgium, and Uruguay also supported the exclusion of political groups (Schabas, 2006). Nevertheless, the lack of political group inclusion in the treaty is the main reason why it has been virtually impossible to convict Latin American military dictators for acts of genocide. Therefore, at least in part, the Soviet Union is responsible in this matter (which, for many, couldn’t have been fortuitous, considering the mass extermination policies already executed by Stalin himself).

From Genocide to Hope

In the early 1980s, El Salvador had a population of 4.5 million. The genocide and civil war left around 75,000 people killed, and between 5,000-10,000 missing. Thousands became victims of torture and sexual abuse, and more than 20% of the country’s total population was displaced (Commission on the Truth for El Salvador, 1993). Both governmental and guerrilla forces committed serious violations of international law that affected combatants and civilians, but the large majority of violations were perpetrated by the former.

Nonetheless, more than 25 years have passed since the signing of the Peace Accords in 1992, and virtually all the massive atrocities committed in the 1970s and 1980s in El Salvador remain in impunity. The victims of political violence were erased at the national level and in the international community. While violence in the country remains extremely high, its source is now mainly associated with gangs and organized crime.

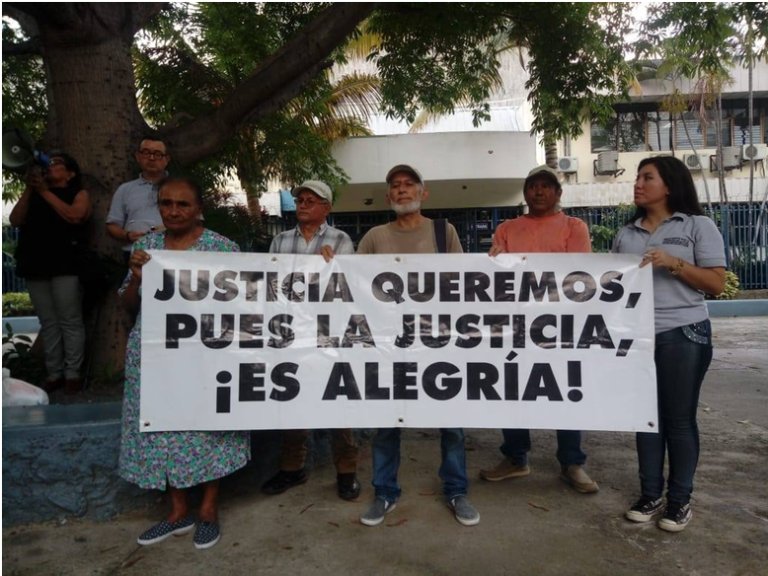

Civil Society organizations’ demonstration in San Salvador.

Source: Cristosal

While this type of violence gets most of the attention nowadays, the relatives of the disappeared still hope to find out what happened to their loved ones someday. Victims of torture, rape and sexual abuse have not even received recognition or reparations for their suffering. State institutions in general don’t seem to be truly committed to supporting them.

At the time, it seemed that the platoons and death squads were going to get away with their heinous crimes. But, survivors and victims’ relatives never gave up. After decades of struggle, in 2016, the Constitutional Chamber declared the Amnesty Law that hindered the prosecution of the atrocities committed during the armed conflict unconstitutional. Rufina Amaya died in 2007 and failed to see this declaration, but thanks to her testimony and courage, along with that of other survivors and their relatives, today 17 former high-ranking military officers are being tried by a local court for their alleged responsibility in the El Mozote massacre.

Only a couple of local media outlets are covering the trial of one of the worst massacres in the history of Latin America and few national and international organizations have been able to continue supporting the survivors of this violence. But, that hasn’t stopped them. With everything working against them, survivors have succeeded in putting senior officers, who were untouchable at the time of the “scorched-earth” operations, before a judge. Among the officers facing trial are José Guillermo García, minister of defense between October 1979 and April 1983, Rafael Flores Lima, joint chief of staff of the armed forces in 1981, and Juan Rafael Bustillo Toledo, head of the Air Force between 1979 and 1989.

As in many other cases, the Salvadoran genocide will arguably never be recognized as such by a court and, quite rightly, legal proceedings will instead refer to these acts as crimes against humanity or war crimes. But, as with the Cambodian genocide, outside the purely legal scope, it is possible to perpetuate a memory of these events as those of a genocide.

The El Mozote Massacre trial will be a crucial test for the credibility of El Salvador’s judicial system. Victims of thousands of atrocities have not lost hope and are pushing for the advancement of other related cases.

They know the time has come. They know it is part of their legacy.

They can finally dream with breaking impunity. Will they?