Since assuming office, U.S. President Donald Trump’s attempt to systematically dismantle the environmental legacy of his predecessor, Barack Obama, has led some commentators to describe his approach to the environment as “clueless” and “dangerous.”

As of January 31st, 2018, the Trump administration had canceled over 30 Obama-era regulations on climate change, energy, and the environment with over 30 more on the way out. Meanwhile, climate change has forcefully divided the American electorate and Congress, as well as the last two presidential administrations, whose positions on the issue stand in stark contrast.

Ice storm rolls from Texas to Tennessee – I’m in Los Angeles and it’s freezing. Global warming is a total, and very expensive, hoax!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 6, 2013

“Climate change is not a hoax. More droughts and wildfires are not a joke. They’re a threat to your future.”—President Obama

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) October 9, 2012

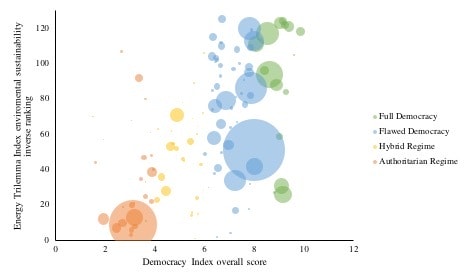

This morbid decline in actions designed to halt climate change in the United States seemingly flies in the face of a broader trend: namely, countries that tend to be more democratic also tend to take more action on climate change (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Environmental sustainability and democracy in 124 countries, weighted by GDP (USD-2016) – Obama environmental legacy

Data: World Energy Council; World Bank; The Economist

In fact, “conventional wisdom” in many political science disciplines holds that “democracies are more likely than non-democracies to care for the environment in general,” and climate change in particular.

What do the recent “clueless” and “dangerous” actions of the Trump administration say about our conventional wisdom? How do they compare to the logic underlying the popular claim that democracies are more climate friendly than non-democracies?

The answer necessarily entails some good news, some bad news, and some news in between.

The Bad News

The bad news is that effectively managing climate change requires sustained action in the long run, but the machinery of electoral democracy in the United States gives elected officials an incentive to prioritize short-run decision making.

As an unsurprising consequence, Donald Trump has sacrificed long-term gains on climate change for short-term political tokens that appeal to his voter base.

Consider Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement. The terms of the agreement prohibit countries—the U.S. included—from retracting their commitments until the year 2020, which means that, for now, Trump will have to wait. A coalition of more than 20 states, 110 cities, and over 1,000 businesses and universities has also declared its support for the Paris Agreement in spite of the Trump administration. And though it may have played well with his base, Trump’s decision lacks support among voters nationwide.

Pulling the United States out of the Paris Agreement, however, allows Trump to claim he fulfilled one of his campaign promises despite undermining U.S. leadership on climate change. Of his decision, the New York Times wrote that it was a political tactic predicated on “cultivating the narrower conservative base that delivered him to the White House” in the first place with the hope of repeating the effect during the next election cycle.

Elected officials like Donald Trump in the United States sometimes face a perverse incentive to count regressive action on climate change as a political victory that could propel their future electoral success.

The Good News

The good news is that democracies like the United States are generally responsive to voters, who could demand action as they increasingly feel the effects of a changing climate.

Belief in climate change has certainly declined among conservative Republicans since Trump’s inauguration—nine percent in fact—but that’s not the whole story.

According to the newest public opinion maps and New York University professor Patrick Egan, conservative opinions on climate change often vary based on “where liberal and moderate Republicans live compared to conservative Republicans.” However, they also vary among Republicans living in areas of the country especially vulnerable to climate change. For instance, in southeast Florida, where sea-level rise occurs an estimated six times faster than the global average, 56 percent of Republicans believe in climate change, compared to just 50 percent of Republicans nationwide.

Voters’ impact on their elected officials could matter a great deal if it translates into positive action on climate change in the long run. Some outspoken environmentalists like Al Gore are “extremely optimistic” about people “organizing to insist on… change.” After all, the People’s Climate March in New York City attracted almost 400,000 people in 2014 and demonstrated widespread popular support for combating climate change.

Yet, while such laudable activism can demonstrate citizens’ desire for change, “voting remains the most direct way to influence governmental policy” in a democracy. If the 50 percent of self-declared environmentalists who turned out to vote in the last presidential election convinced the other 50 percent of the movement to do the same, then they could potentially bring about action on climate change through the polls.

The In-Between

Clamorous debate exists concerning the relationship between democracy and climate change. (The journal Democratization published an entire issue specifically dedicated to understanding this relationship in 2012.)

Some claim the question does not pertain to democracy per se, but rather “democracies with adjectives.” Others argue in favor of studying this relationship over time to account for intervening historical variables, such as corruption and “democratic capital stock.” Still others consider the distinction between Earth’s human and non-human systems, such as democratic politics and the climate, neither natural nor inevitable. And, of course, it goes without saying that the absence of climate leadership nationally in a democracy may not necessarily inhibit action at local levels, as duly noted elsewhere.

For now, the question of how democracy interacts with climate change remains an open one, and one which undoubtedly warrants greater focus and a finer-grain analysis than the scope of this article permits.

Until we fully understand this relationship, claims that democracy is the answer to climate change deserve to be met with a healthy dose of skepticism. Silver-bullet promises to stop climate change in its tracks do little more than to obfuscate the complex interrelationships between the earth’s climate system and human beings’ political systems.

Cases like the Trump administration and its all-out offensive on climate action illustrate the sometimes-capricious nature of democracy and force us to reexamine our conventional wisdom about democracies’ ability to squarely confront the problem of climate change. Just as the stroke of a pen can commit democracies like the United States to bold efforts to thwart climate change, so too can future penstrokes unmake those commitments.