There is a twilight zone lived in by family members of the disappeared. Daily life, joys and frustrations happen against an internal backdrop that is difficult to share. Gulruy Asqar writes movingly about this in Missing: Loved ones in East Turkestan. She details what should be a normal, joyful day as a kindergarten teacher and mother. Instead, she is imbued with the anguish of feeling powerless to help her own brother and nephews somewhere in the Uyghur camps and prisons in China.

It is possible to do more than read, sympathize and share the story.

To act effectively is not hard. However, it requires a mind shift. I have lost patience with conversations that expound on how “they” should fix the problem, or what, “everyone” ought to do.

If I truly want to fix injustice, I have to get connected to it, to pull it in closer. With technology now it is so easy to do this. To turn “I” not into “They”, but into “We”.

For every person disappeared or detained by an authoritarian regime, somewhere there are family members in the twilight zone, feeling helplessness and despair. While it takes some legwork and relationship building, it is very possible to reach those families.

Personal Connections are Transformative

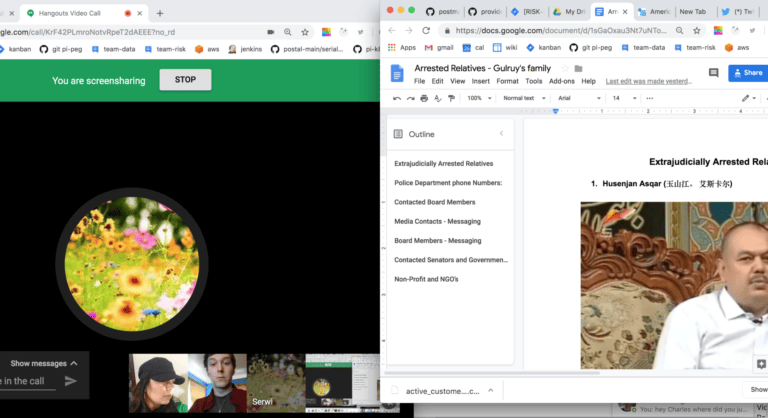

Knowing Gulruy has transformed the Uyghur crisis for me. Now that my friend’s brother, nephews and in-laws are part of the million disappeared, doing something about it is not a question. Figuring out what to do next is still a challenge. However, each week a small group of us get on a hangout and try something. We reach out to reporters, lobby elected officials, and brainstorm. Sometimes we come up with creative ideas like calling police stations in Xinjiang with a Mandarin speaker on the phone. Other times we reach out to board members of companies doing business there.

Some strategies result in connections, a bit of progress. Gulruy’s brother, Husanjan Asqer, is still not free, but we hope that by raising his name, perhaps we are giving him some small protection. We continue to try different things. If I were the one in a secret prison, I hope the world would not give up and forget me.

We defend others as well. Abdulraman Al-Sadhan, a Red Crescent worker, disappeared in Saudi Arabia in 2018 and has not been heard from since. We raise his name on social media and blogs and share into others’ feeds. Twitter is a powerful platform, but simply sharing is not enough. We also try to create connections to those who might have the power to help.

Just as it is possible in this connected world to find and support the family members of victims, it is also possible to find and connect to people with some small leverage. A sympathetic reporter, someone who knows someone in government, a business person who considers themselves ethical. These people are out there and we can reach them on social media. Twitter, LinkedIn, and sometimes by email or phone with a bit of research.

Making Connections

When a moving article appears in the news – for instance, the massive protests in Sudan, and the massacre of peaceful protestors on June 3 – it is possible to reach out to the people involved. Two Twitter messages put me in touch with Mohammed Ameen, leader of Sudan Change Now. He patiently explained to a small group of us the history behind the protests. More importantly, he explained that the key thing Sudanese people need and desperately want is a civilian rule that is accountable to the people.

He explained that their fear is that even after so much sacrifice, the military will never carry out the agreement for sharing power with civilians, or investigate those responsible for the massacres. And he also told us that the US and UK have a great deal of influence on this. So we are trying to reach out to State Department officials and ask them pointed questions and to inform our representatives in Congress about these key points.

In asking Mohammed where we should link to, he sent me A Sudanese Declaration in English, which is mainly posted in Arabic.

It all sounds a bit intimidating and overwhelming. Of course, it is. Having a team helps. One can join an organization; many excellent organizations are out there. You may be able to join one and contribute to specific tasks as assigned or to join a committee on a particular issue.

Our Approach

Our group has a bit of a different approach. We use modern software but without a top-down structure. Therefore, each of us can take the initiative. Several loosely structured groups share one slack and support each other, exchange ideas, join into calls and projects. We report to each other in online standups and hold conference calls including some of the family members. We only have a few rules. One rule is that we do not just talk about things without an action item. We do not tell anyone what to do but everyone should have a project, a next step and a deadline.

We take this approach because following any one system, any one set of instructions, may not be enough.

The struggle, if you will, is between decent, caring, freedom-loving people everywhere and those who have assumed power and systematically use violence to crush any opposition. It won’t be easy even to get one victim freed, let alone the millions under their rule. So, it does not feel enough to sort clothes for asylum seekers, donate to a candidate or leave yet another message for congress. I feel a need to be a part of a concerted effort that allows for innovation and initiative.

Sometimes I think of digital outreach like playing soccer. When I am posting Tweets with no replies or leaving messages with no answers, I feel like I am trying to play soccer by blowing at the ball. I need a teammate to pass to, who will look up when I shout, who will pass it back with force and move together with me down the field.

Importance of Teamwork

One way to create this sense of teamwork is to take action jointly while on a video call. We may decide our goal is to find reporters or board members who could have some influence and be sympathetic. Right on the call, several of us rapidly research, while one or two compose the messages to be sent. As we find names and contact information, we send the messages out live, sharing the screen and taking last-minute corrections before pressing send.

What to send is as critical as finding the contacts. The messages we send to board members of companies that do business with dictators are not frustrated accusations. They are factual and personal appeals for help and advice. Assuming that the other person intends to be ethical, ask them, as experts in the region, how to help innocent people possibly being tortured in a prison. This has some chance of a response.

This reaching out through contacts, while perhaps the most powerful method we have found so far, is not the whole answer. We do not know what is. This is why we encourage rapid exploration, trying new ideas and supporting each other in new actions.

Editor’s Picks – Related Articles

“Many Peaces in Iraq: Creating a Foundation for Conflict Transformation Through Peace Studies”

“Youth, a Not-So-Secret Formula for Peace and Sustainable Development”

Leveraging Digital Tools and Social Media

This focus on actions and on teams is more significant than any particular technique. We do try to educate each other on best practices: add all your past co-workers on LinkedIn, even if you never liked them; they might know someone. Write letters to the editor in 150 words or less and make them snappy. Tweet into the feed of an influencer, right when the story breaks. Write longer articles with striking images and link to them in social media. When emailing your State Dept, cc: your member of congress for a higher chance of a reply. Tell congressional offices you are a representative of an organization and ask for the email of the staffer for the relevant issue. Use Signal when talking to anyone who might themselves be a target. Sharing effective techniques is part of what teams do for each other.

Teams have each other’s back, and that also means, especially, the families and those on the front lines. There are brave people all around us in the world who are standing up for freedom – in China and Saudi Arabia, in Hong Kong and Sudan, in Honduras and Cameroon. Some of their stories make the news. Some do not. If you want to be a part of the story, to shape how it is told and how it comes out in the end, you can.

Our current active teams can be found at Volunteer Match.

In the cover picture: Woman filming protest in Boston, U.S. Photo Credit: Alice Donovan Rouse.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.