It has been more than eight months since the novel coronavirus was confirmed in China and more than five months since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic. Because of the fallout from the pandemic by the end of 2020, the United Nations World Food Programme estimates that life-threatening chronic hunger, diplomatically named “food insecurity”, is expected to double to 265 million in developing countries. But the impact of COVID on nutrition doesn’t stop there.

Everywhere, with normal activities and exercise curtailed, new anxieties and depression abound, translating into many simply eating more. “More” means much more comfort food which means higher vulnerabilities for heart disease, diabetes, stroke, weakened immune systems less able to deal with COVID-19, and other infectious diseases, for that matter.

In the Obesity journal, William Dietz and Carlos Santos‐Burgoa, two professors at the George Washington University Milliken Institute School of Public Health, suggest that “…increased prevalence of obesity in older adults in Italy compared with China may account for the difference in mortality between the two countries.”

Regarding the probable impact of COVID-19 on obese patients in the United States, they made an illuminating comparison with the H1N1 influenza virus:

“Between April 2009 and January 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 41 to 84 million people were infected with the H1N1 influenza virus and that between 180,000 and 370,000 infected patients were hospitalized, with 8,000 to 17,000 deaths…Although the effects of COVID‐19 on patients with obesity have not yet been well described, the H1N1 influenza experience should serve as a caution for the care of patients with obesity and particularly patients with severe obesity. The prevalence of patients with obesity, severe obesity, and COVID‐19 infections will increase compared with the H1N1 experience, and the disease will likely have a more severe course in such patients.”

Those in lower economic status and with less education — and they often belong to ethnic and racial minorities — are more likely to be overweight than those in better circumstances.

This situation is not limited to OECD countries, the world’s “rich” countries.

According to a World Bank study on the health and economic consequences of obesity, more than 70% of the 2 billion overweight or obese live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Rapidly changing food systems in these countries allow cheap ultra-processed foods to reach the poor even in rural areas. This access is coupled with the “better off” urban or semi-urban populations that often have access to better healthcare services than their poorer counterparts.

In short, there is worldwide obesity exacerbated admittedly indirectly by the COVID-19, and this is the “Upstairs” story.

The COVID-19“Downstairs” story is a nutrition tale that has variously been described as undernutrition or malnutrition.

World Bank economists predict that the pandemic will push 71 million people into extreme poverty, resulting in the first increase in global poverty since 1998, alongside dramatic deteriorations in LMICs’ economic growth.

Poor populations are more dependent on public services especially healthcare facilities than the better off middle and upper classes. The availability and access to health workers and health systems, already problematic, are enormously affected by COVID-19.

A recent Lancet study notes that hypothetical reductions of health service coverage of 15-45% for six months would result in 10-45% increases in deaths of children under 5 years of age, every month. Increases in child wasting would be the largest contributor to these estimated deaths across 118 countries in the study. Furthermore, other unfortunate outcomes are likely increases in preventable diseases such as measles and cholera, accompanied by decreases in vaccination campaigns and malaria programs that are particularly important in Africa and South Asia.

According to the 2020 Global Nutrition Report, the distribution of nutrition professionals across the world is not equitable, and this was the case even before the pandemic: The global median is 2.3 nutrition professionals per 100,000 people, while in the Africa region the median is 0.9, with some countries having none. And disruptions to already inequitable health and nutrition services will be further compounded by the social and economic effects of COVID-19, which will likely further disadvantage the poor and most vulnerable.

With the economic shocks of COVID-19 already being felt and likely to expand, there is growing concern that poor households may be compelled to eat cheaper, less nutritious food that is more easily available — and in some cases, it may not be available at all. This would perpetuate unequal nutrition outcomes and further increase vulnerability to stunting, obesity, malaria and associated non-communicable diseases which increase the severity of COVID-19 symptoms. A New York Times article “The Other Way That Covid Kills” provides multiple examples of the direct and indirect impact of COVID-19.

In terms of food production and therefore availability, there are major consequences, especially in developing countries. The threat is greatest in countries where malnutrition is already high yet agricultural production, often carried out by aging, vulnerable farmers, remains the backbone of the economy. In several African countries, including Kenya, Mali and Chad, agriculture, forestry and fishing account for more than a third of gross domestic product (GDP) and as much as 58 percent in Sierra Leone. Further, while women bear heavier farming burdens in many cases, women are not only the primary “food providers” for their households, but also makeup almost half of the agricultural labor force in developing countries.

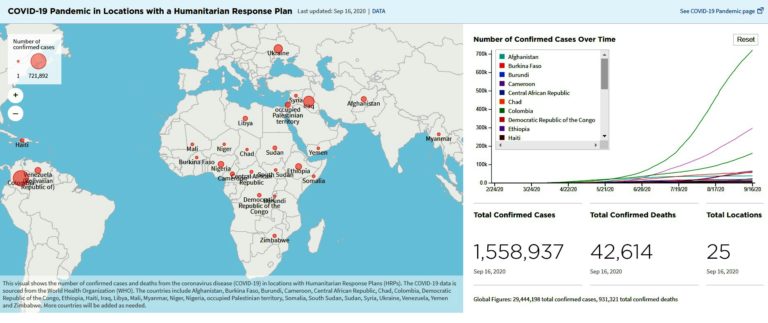

As Mark Lowcock, the head of OCHA — the UN’s humanitarian arm — says in the above video, it is estimated that it would only take $90 billion — a relatively modest sum — to protect 10 percent of the world’s most vulnerable population from the worst effects of COVID-19 and avoid, as he put it, the worst “human tragedies” in the developing world.

The G-20 statement put together over the summer broadly described good intentions to support developing countries in responding to the intertwined health, social and economic impacts of the pandemic. It did not go into detail as to how the international community would proceed to deal urgently with direct and indirect nutrition needs and consequences. Now activists, and prominent among them, Amnesty International, are calling on the G-20 Health and Finance Ministers to “demonstrate global leadership” by adopting a better and more concrete plan at their meeting on 17 September 2020: We will see if there are the political will and resources to do so.

In sum, as the Global Nutrition Report points out, poor diets are not only a matter of personal food choices but other factors impact many of the most vulnerable people.

Whether “Upstairs” or “Downstairs”, individual and collective wellbeing, for different reasons, depends on nutritional availability, access opportunity, and making choices. In the COVID 19 era, we need to do much better. And we, in the “rich” countries, have the means to do it.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com Featured Image Source: OCHA page for COVID emergency activities