COVID-19 hit the hospitality industry hard and many governments around the world reacted with a variety of support measures. The United Kingdom’s one-month “Eat Out to Help Out” program stands out as a roaring success, with 84,700 restaurants that have signed up and claimed 100 million meals.

Begun in August 2020, it was designed to pay 50% of a diner’s restaurant bill for meals and soft drinks for the days that are traditionally “empty”, Monday through Wednesday. This was a way to rescue massive numbers of unemployed unskilled and semi-skilled workers in the hospitality industry, a crisis triggered by COVID 19. In the United Kingdom, around 80% of hospitality firms stopped trading in April, with 1.4 million workers furloughed, the highest of any sector.

The jump in demand was confirmed by data gathered by the booking site Open Table showing that restaurant reservations rose by 53% in 2020 compared with the Monday-to-Wednesday period in August 2019. The BBC reported (4 September) that Chancellor Rishi Sunak, while noting that “today’s figures continue to show Eat Out to Help Out has been a success”, ruled out extending the scheme – presumably bowing to criticism that the costs were unsustainable for the Treasury. The BBC also reported that some pub and restaurant chains, including Pizza Hut and Bill’s, have said they will finance similar offers in September. Whether that is a workable marketing ploy and how much it can help in the long run remains to be seen.

The vulnerability of the hospitality sector workers to COVID-19 is a global phenomenon of massive proportion. The reason is that in the pre-COVID world, there had been a massive shift from the manufacturing sector to the hospitality industry as a result of prosperity that had grown in virtually all regions in the world.

Apparently ever-growing numbers of people with disposable income and greater mobility were eating out and spending time and money on leisure. As a result, there had been a commensurate expansion of work in various hospitality areas requiring little or minimal skills, with a proportionate labor force decrease in the manufacturing sector. In normal (non-COVID) circumstances, this helps provide diverse employment opportunities for migrants, women, students, and older workers, not only in major cities but also in remote, rural and coastal areas, as well as other often economically fragile locations where alternative opportunities may be limited

As of mid-2020, over 90% of workers are in countries with some form of workplace closure. Almost one-third were in countries with required workplace closures for all but essential workplaces. Regions differ significantly with the most affected in the Americas while no country in the Arab States or Central Asia stipulated such closures.

According to ILO data, from April to June 2020 (second quarter of 2020), working-hour losses relative to the same period in 2019 were estimated to be 14 percent worldwide, with the largest reduction (over 18 percent) in the Americas. The outlook for the second half with an optimistic scenario of a fast recovery will not bring work to the pre-crisis level, and if there is a second wave of the pandemic, losses could continue to be nearly as high, around 12%.

The World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) estimates that the tourism industry accounts for 10% of the world’s GDP and jobs would shrink by an estimated 25% in 2020 and “shed 50 million jobs”.

Of those 50 million lost jobs, around 30 million would be in Asia, seven million in Europe, five million in the Americas and the rest in other continents. A loss of three months of global travel in 2020 could lead to a corresponding reduction in jobs of between 12% and 14%, the WTTC said, also calling on governments to remove or simplify visas wherever possible, cut travel taxes and introduce incentives once the epidemic is under control.

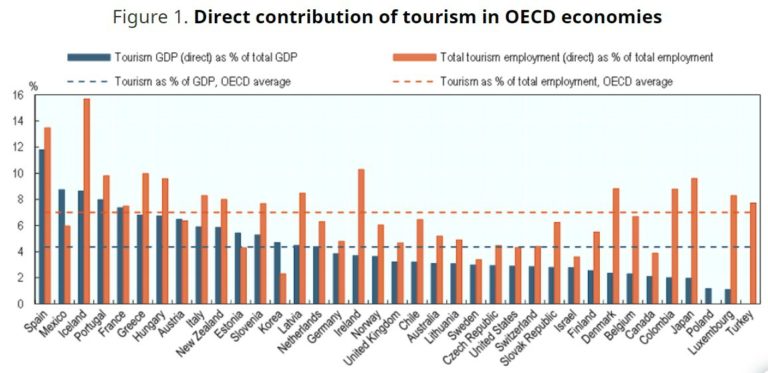

OECD projections for the tourism economy in wealthy countries are equally bleak. With tourism contributing to nearly 7% of employment in OECD countries, COVID-19 will lead to a 60% decline in international tourism in 2020, which could go to 80% if recovery is delayed until December.

For example, the share of tourism employment represents 15.7% of total employment in Iceland, 13.5% in Spain, 10.3% in Ireland, 10.0% in Greece, and 9.8% in Portugal. International tourism within specific geographic regions (e.g. in the European Union) is expected to rebound first.

The case of the United States’ Hospitality Industry

The United States is worth considering independently given its economic size and its leisure industry. In May 2020 over 52% U.S. small businesses in the leisure and hospitality industry reported temporarily closing, and 35.2% reported a decrease in the number of paid employees. With business closings and permanent or temporary layoffs, it translates to deepening income disparity and inequality. The reason is that racial minorities as well as female workers, and the young with less education, perform many of the hospitality tasks.

The U.S. Government’s Paycheck Protection Program (a.k.a. PPP) is designed to provide small businesses with funds, some $659 billion to support job retention and other expenses, for many firms in the hospitality industry.

This is all to the good but it is well accepted that much more will be needed. People in the industry suffer at all levels, managers included, and see it as turning into a prolonged struggle for economic survival with no clear exit in sight.

As the Best Western CEO points out in the above video, the range of problems is stunningly broad and includes migrant workers and the new gig economy. For example, AirB&B (which is scheduled for an IPO this month) is equally impacted by COVID and may have to face an uphill fight of its own to give its clients safety assurances in pandemic times, something that is easier to do for the more regulated traditional hotel industry.

Help for the Hospitality Industry Across the World

But the problems are not limited to the United States. Below, are other examples of the ways developed and developing countries are dealing with the challenge:

Bhutan

The National Resilience Fund for mitigating COVID-19 linked job losses and salary cuts and the government has deferred tax payments for tourism and related sectors until December 31, 2020.

Canada

The Federal Government is providing around $85 billion (4.0 percent of GDP) in liquidity support through tax deferrals. Moreover, a series of relief programs have also been set up for the restaurant and hospitality industry.

Italy

Privately owned and managed hotels account for a greater proportion of the market than chain hotels in Italy. Government measures to stem the impact of the COVID-19 lockdowns included commitments to pay 80% of total wages of workers furloughed because of the crisis and loan guarantee assistance. The government also launched a program of holiday vouchers (called Bonus Vacanze) to promote domestic tourism for Italian families with incomes below a certain level.

Germany

There is no overall federal policy. Each State has taken separate actions, such as Baden-Wuerttemberg which committed 330 million Euros for the hotel and catering trade.

Mexico

Recently the Washington Post reported a story about Cabo as an example of the problems encountered by Mexico’s hospitality industry, highlighting that “at stake was nearly all of Cabo’s economy — 80 percent, according to official statistics.” International flights into Cabo — its main source of visitors — were down 93 percent from last summer.

Tourism is in fact the third biggest contributor to Mexico’s GDP at nearly 9 percent. With COVID, that number dropped close to zero. The Mexican ministry of tourism does not expect conditions returning to “normal” before 2023.

South Africa

Companies and workers facing distress can get assistance through the Unemployment Insurance Fund and special programs from the Industrial Development Corporation. Specific funds are available to assist small and medium-sized enterprises under stress, mainly in tourism.

Each of the above represents countries in different circumstances that are trying to provide some relief to the hospitality sector and its workforce. What is striking is the fragmented, piecemeal approach. Clearly no overall solution is proposed.

Even once therapeutics and vaccines become available, we need to realize that, no matter how helpful they may be, there is no way that we will go back to the way things were before COVID. Undoubtedly, many small operations will be lost. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the hospitality industry will quickly if ever regain past levels of activity — close restaurant dining, full occupancy at hotels, cruise lines, or resorts and vacation air travel may well become things of the past.

Among the most at risk and most harmed is the hospitality workforce: Many fewer positions will be available and there will be a likely need for different and probably higher-level skills. For those already working in the hospitality industry, they will have to be recycled and retrained. Opportunities for education and new skill training will have to be provided.

In short, a new way of thinking about tourism is needed. Hard today to find countries or industries to take this on, but one can only hope they do so in the future.

The fact that some people are already working on that and coming up with alternate proposals, including for “more sustainable travel”, is definitely encouraging. For example, a new edition of the Sustainable & Social Tourism Summit will be held on 8 and 9 September 2020 in the form of a virtual meeting under the name “A new opportunity, a new tourism”.

There is no question that the stakes are high and the challenges are formidable but solutions might come soon. We need to keep a close watch on what eventually emerges.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.Featured Image: A terrace on Piazza San Marco, Venice, Italy. June 2020: Tourists return as Italy opens its borders. Source: Head Topics