COVID-19 created a healthcare workers crisis now, but worse is yet to come. The pandemic has placed extraordinary and inordinate demands on healthcare professionals of every stripe, including doctors, nurses, public health specialists, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, technical and clerical assistants, field epidemiologists, veterinarians, wildlife and food inspection services, hygiene and maintenance service providers, and more.

Moreover, mandatory social distancing, separation from family and friends, masks, and heightened senses of isolation and fear of the pandemic has had the unique effect of greatly heightening the need to address essential “patient-centered” physical and emotional needs – placing yet more pressure on the healthcare workforce. If you are one of them and the stress is starting to build up, consider using natural aids to get rid of it like the Delta 8 carts.

What is needed is an urgent massive acceleration in health professional faculty, infrastructure, and support for student financing, to meet anticipated demand and respond to changing technologies and advancing models of integrated health and social care. But first, before detailing what measures need to be taken, let’s take a closer look at the situation.

The impact of COVID-19 in 2020 has meant that existing health-related human resources have had to be significantly diverted from services needed in ordinary times, develop new skills, at the same time their numbers are declining whether from virus exposure and resultant morbidity or death, moral distress or burn-out from the pressures and effects on mental health.

Because this virus continues to expand in many places, there are no definitive numbers of the losses across the world. There is much anecdotal and testimonial evidence this is not minor or temporary in most countries.

Understandably to a degree, global attention is focused on finding and distributing COVID therapeutics and vaccines. However, few observers if any are focusing on the prospect of massive losses in the healthcare workforce and the need to replenish and significantly expand the numbers of health professional which will be needed.

The need will be not to just deal with COVID, but more importantly, to address the myriad of diseases, conditions, and demands for preventive and curative health services that will need a response but go unanswered.

For perspective, consider what we “thought” in the pre-COVID era.

The 2006 World Health Organization Report provided a simple measure of healthcare worker needs based on the density necessary to achieve 80% coverage of essential health services. That percentage meant a ratio of 23 healthcare workers for 10,000 people would be needed to adequately provide for primary care coverage. In the following years, this ratio underwent analysis, revision as new information and technology emerged, but as the WHO data dashboard shows, even with all that, performance has fallen far short by any measure.

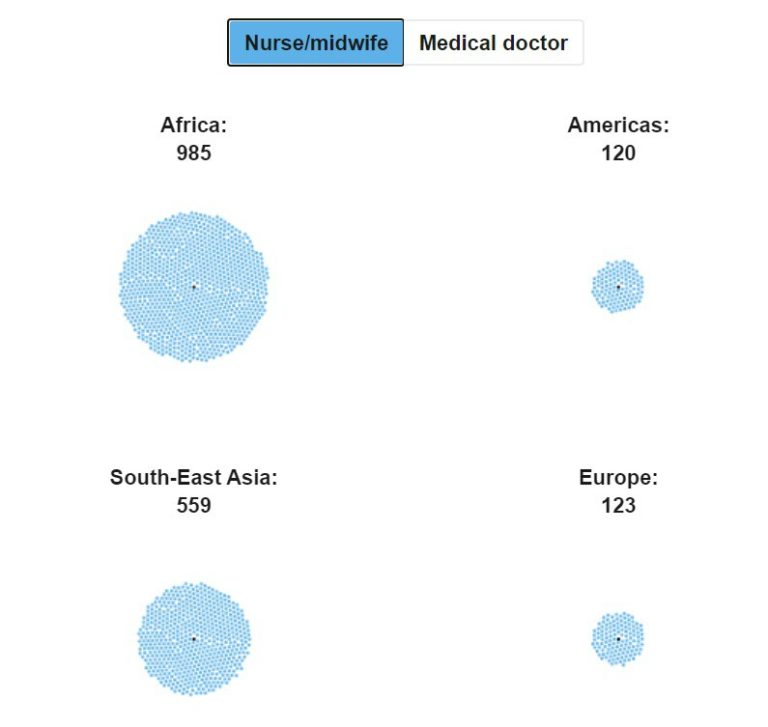

The number of people for every single nurse/midwife is only (barely) acceptable in developed countries – America and Europe – while the rest of the world shows unacceptably high numbers for every health worker:

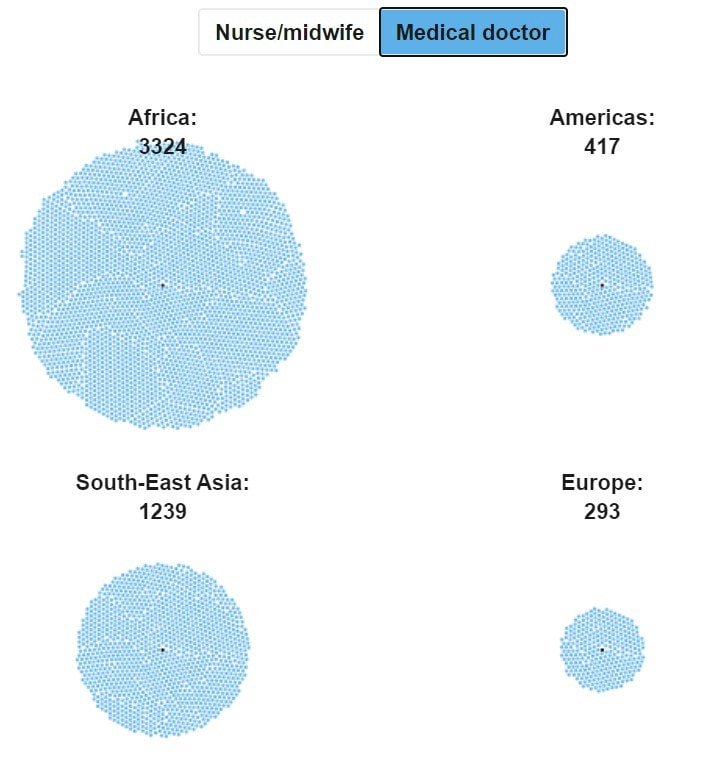

Likewise, the number of people for every medical doctor is unacceptably high everywhere except in America and Europe:

In 2015, with the adoption of the 2030 Agenda and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, nations endorsed the aspirational goal (SDG#3, target 3.c) to:

Substantially increase health financing and the recruitment, development, training and retention of the health workforce in developing countries, especially in least developed countries and small island developing States.

The aim was to achieve, by 2030, “Universal Health Coverage”, which would include access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

In 2018 the World Health Organization (WHO) projected a shortfall of 18 million healthcare workers by 2030, mostly in low- and lower-middle-income countries. It noted, however, that countries at all levels of socioeconomic development face, to varying degrees, difficulties in the education, employment, deployment, retention, and performance of their workforce.

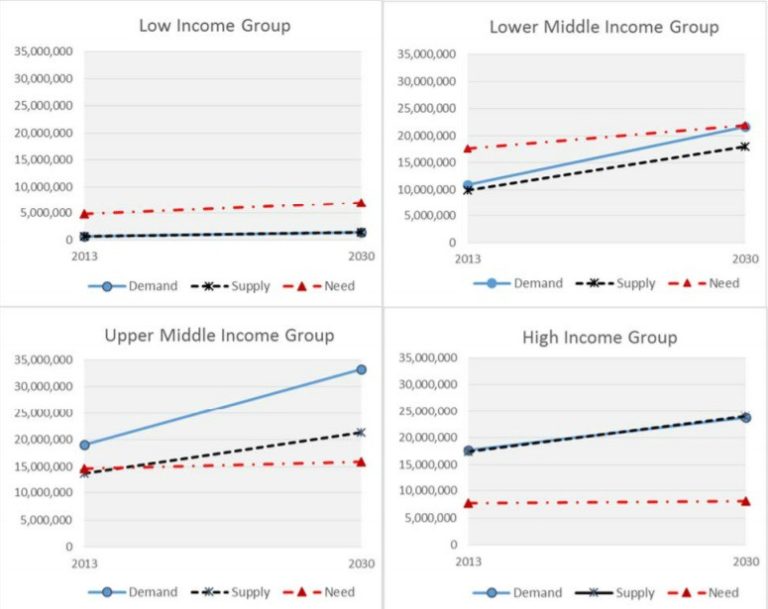

A World Bank study went further: In 2016, based on data from 165 countries from the World Health Organization’s Global Health Observatory, comparing the projected growth in healthcare worker supply and worker “needs” as estimated by the World Health Organization to achieve essential health coverage, the World Bank’s model predicted that by 2030 global demand for healthcare workers will rise to 80 million workers, double the current (2013) stock of health workers.

The supply of healthcare workers is expected to reach 65 million over the same period, resulting in a worldwide shortage of 15 million health workers.

Growth in the demand for healthcare workers will be highest among upper-middle-income countries, driven by economic growth and population growth and aging, resulting in the largest predicted shortages, which may fuel global competition for skilled health workers.

The authors of the study have neatly summarized their findings – trends in demand, supply and need‐based number of healthcare workers for each World Bank income group over the 2013‐2030 period – in the following graph (on p.17):

Middle-income countries will face workforce shortages because their demand will exceed supply. By contrast, low-income countries will face low growth in demand and supply, but they will face workforce shortages because their needs will exceed supply and demand. In many low-income countries, demand may stay below projected supply, leading to the paradoxical phenomenon of unemployed (“surplus”) healthcare workers in those countries facing acute “needs-based” shortages.

These were projections based on available data modeling at the time and are now essentially irrelevant. We have learned only too well that models need constant revision to reflect new data and realities. None of the above could have anticipated the ongoing 2020 global pandemic and its impact on the health workforce, the effect on or losses of workers, insufficient numbers of newly trained professionals at learning institutions, changes in types of health services needed, the potential for of telemedicine, and so forth.

Focusing on the supply side, worldwide production of doctors and nurses has fallen far behind what is required.

For most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) this would be the challenge to train enough healthcare workers and physicians to simply be able to keep pace with what their people need at home. But their problem is further exacerbated by their own economic weakness and the competing economic magnet of developed country health facilities whether in North America, Europe, the Pacific, or oil-rich countries of the Middle East.

This is caused, in major regards, by insufficient richer country investment in their higher health education institutions to meet their own needs.

To take one country example – the United States – Dr. Kate Tulenko, in her 2012 book entitled Insourced: How Importing Jobs Impacts the Healthcare Crisis Here and Abroad, wrote:

“Approximately 15 percent of all healthcare workers and 25% of all physicians in the United States are born and educated elsewhere…This means that 1.5 million healthcare jobs are “insourced”, occupied by foreign-born, foreign-trained workers” leaving tens of thousands of qualified nursing school and medical school applicants without places in health schools each year, while already trained and often experienced workers from low and middle-income countries are enticed to migrate, resulting in the loss of that skill to the health care system from which they come and likely are more needed.”

The gross figures in the book have changed since it was published – some for the better some for the worse- but they are certainly different now. As to bringing in greater numbers of healthcare workers and physicians to the rich, there have been efforts to limit aggressive recruitment industry efforts, such as the 2003 Commonwealth Code of Practice for the Recruitment of International Health Workers which goes out of its way to specify it is not a legal document but states:

7. The Code guidelines for the international recruitment of health workers in a manner that takes into account the potential impact of such recruitment on services in the source country.

8. The Code is intended to discourage the targeted recruitment of health workers from countries that are themselves experiencing shortages.

In the case of the United States, health professional recruitment has encountered hardened immigration policies whether from certain geographic regions, ethnic backgrounds, or limits on the overall numbers of visas. Notwithstanding, the process of cherry-picking continues apace, whether vying for the best developing country doctors from Sub-Saharan Africa or nurses from the Philippines, and both from many other places.

With the impact of COVID-19, most of the health corps of the West have been decimated to a far greater extent than ever before. With a most damaging impact on emergency and primary care capability, in places of greatest geographic need, whether because of closures of facilities or because regional or local clinics never existed or were chronically understaffed.

These shortages are real, will continue to grow, and represent a COVID-19 imposed health workforce nightmare in 2021 and well beyond.

Healthcare Workers and Physicians: How to Meet the Urgent Future Needs Resulting from COVID-19

The lag time from investment to a new healthcare worker is long. Not seen or heard are loud voices of leaders in the developed world calling to prioritize expanded health training institutions to provide academic space for additional future graduates.

The problem is compounded by limits on even finishing the education of existing students, or having them take the necessary certification tests to join the health workforce.

There are seemingly legitimate reasons for this, including the near-term reliance on zoom education which entails extremely limited laboratory or practical training opportunities. Moreover, many higher education structures rely on national and state budget contributions to operate and those have been slashed with the accompanying economic debacle. Last but not least, the numbers of merit-based student applications will be constrained by their family financial circumstances battered by the coming COVID-induced economic depression.

All this being true, with trillions of COVID funding being authorized in Europe and North America, investment in health workforce education is not anywhere close to being on the list of highest priorities today.

Unless we “pay” now for new health professionals, our “health” will pay much more in the future.

To address a possible pathway to be where we need to be, below are broad “financing and compensatory” recommendations:

- Expand financing dramatically for U.S. medical and nursing education. A rough estimate of the total cost of this higher health education is US$25 billion per year. The total annual health expenditure in the U.S. is around US$3.5 trillion. Thus, less than 1% of total health expenditure in the U.S. is spent on health and medical education. New investment in health professional education needs to be ramped up at “warp speed”.

- Significantly increase remuneration now for health professionals and for complementary supportive service hygiene and maintenance personnel. If we are in a “war” with the virus those on the front lines should be compensated for their risks and sacrifice. COVID-19 has already, and will in the future, put pressure on current health workers, ultimately meaning fewer workers, and for those that stay, reduced effectiveness. Words of appreciation need to be translated into action. The U.S. Government needs to put incremental money in their pockets for the rest of 2020. And on into 2021 if need be, to continue to encourage their motivation, personal sacrifice, contribution to societal and economic wellbeing.

Compared to the trillions of COVID-19 U.S. dollar and Euro funding allocated for the myriad of purposes already on the table, the amounts would be modest, the gains enormous.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Featured Image: COVID-19 Frontline Health Workers Scenes of healthcare workers at Thailand Bamrasnaradura Infectious Disease Institute, Ministry of Public Health. Photo: UN Women/ Pathumporn Thongking