What we think we “know” about COVID-19 infection and death rates on a global, regional, and country basis is patently mistaken, based on unintentional or intentional incomplete or false information.

There are various reasons these numbers are off the mark, first as to the numbers of infections: Mistaken identification of the cause (early symptoms of COVID can readily be misdiagnosed as influenza): where there is asymptomatic infection and no testing done, it means the infection is never diagnosed at all.

Next, in the absence of any, or mistaken determination of the cause of deaths, the reasons include: The recorded cause may be simply wrong; and, even more likely, no record exists because some 100 countries do not have a functioning civil registration and vital statistics system that record deaths (Vital Strategies).

Even in those rare cases where there is such a registry, it is rarer still that there is a clinical autopsy. Such information in rural areas of developing countries comes primarily from so-called verbal autopsies, obtaining an approximation to the cause of death by interviewing relatives, friends, or care providers of the deceased person. Without laboratory facilities and trained pathologists, it becomes even more problematic to attribute death to an infectious disease.

The often-quoted cliché “What isn’t counted doesn’t count”, is very much the case when it comes to infectious disease infections and deaths, and what external donors are willing to fund. Dr. Prabhat Jha, Director of the Center for Global Health Research based in Toronto, put it this way, “The main benefit of having data on who dies, and when (where and from what), is to be able to understand what can be done about it today.”

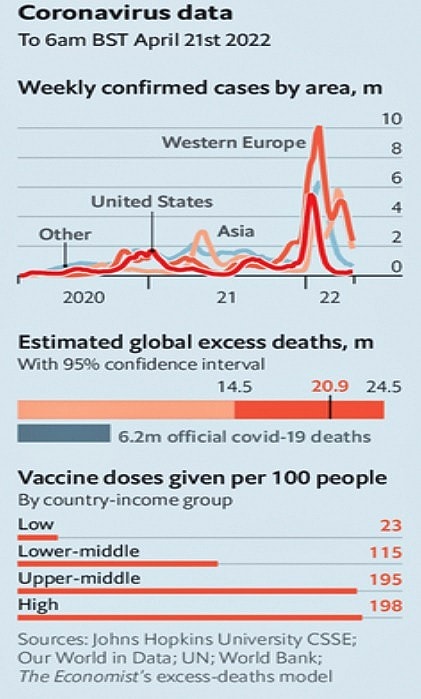

Recently the World Health Organization (WHO) increased its global death toll estimates from the coronavirus pandemic to a total of about 15 million by the end of 2021, more than doubling the earlier official total of six million reported by countries. A major increase to be sure, but good reasons to think that even this increase is far from the full story.

The Economist weekly publishes an unofficial “Excess Mortality,” estimate which is much, much higher, per the graph below from April 23, 2022 (U.S. Edition, screenshot):

Developing Country Overview

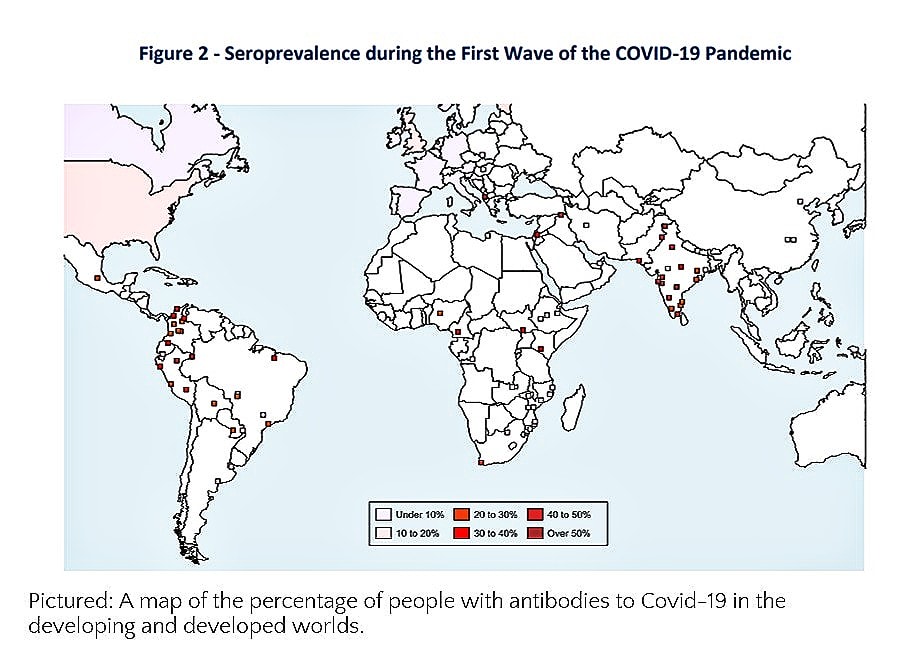

To the extent that there is enough collected information on which to make sound determinations, in general, low-income countries have had more trouble controlling the pandemic and protecting their elderly populations.

Older people are more likely to die from Covid-19, so if older people are getting infected more often in low-income places it means the overall death rate will be higher. We also know that in several developed countries nursing homes early on were missed as places with high levels of Covid infection and should have been a priority.

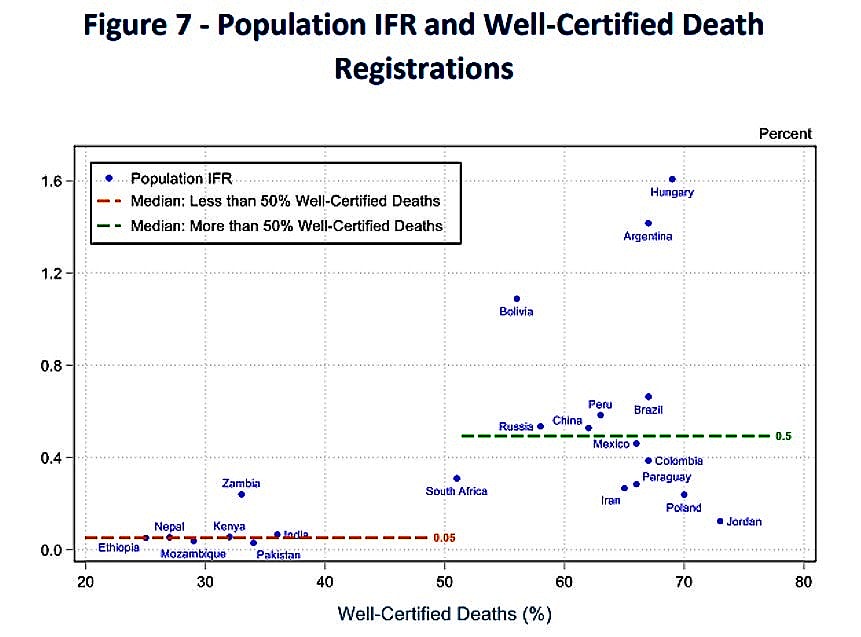

Indeed, when you compare the infection fatality rate (IFR) between places with decent death reporting systems and those without such systems in place before the pandemic, the death rate is about 10 times higher in places that report deaths adequately.

In other words, the main difference between places with apparently very low Covid death counts (despite high infections) and their counterparts is probably just how those places record deaths.

To better understand how this plays out, let’s take a closer look at various cases of underreporting: India, a major country, and Africa.

Examples of underreporting

India: a major country affected by poverty and limited education in rural areas

More than a third of WHO’s additional nine million deaths are estimated to have occurred in India, where the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has stood by its own count of about 520,000.

However, WHO’s new numbers for India are likely to fall far short of the whole story.

Basic data suggests that significant segments of rural population statistics are missing in light of other variables:

- Up to 23 million households in India (in over 292,000 villages) are without electricity;

- 7% (43,000) of the villages are without mobile services;

- 17% of rural habitations are without clean drinking water;

- 25% of 14- to 18-year-olds (nearly 88 million) who live in rural areas cannot read a basic text in their own language, so the likelihood they will understand COVID-19 is dubious.

Africa: a Region with Few Death Registries

Just one in 10 deaths in the continent is recorded according to the WHO SCORE Assessment Instrument launched in 2018. This in itself undermines reliability efforts at monitoring global health outcomes since of the 18.2 million unregistered deaths across the world in a year, over 8 million or 46 percent are in Africa.

While such numbers might have improved in the last few years on the margins, Africa’s annual average of 9,285,000 deaths between 2013 and 2018, only 921,000 were registered. And only one out of 47 countries has a sustainable capacity for public health surveillance.

To put the matter in perspective, let’s now turn to another major country, the People’s Republic of China, where reporting is considered, by all measures, to be excellent, if not actually overbearing and intrusive of personal privacy.

And China: What of Its Covid Future?

China has had a highly sophisticated health information system that reports the where, when, and what of infections and causes.

With respect to Covid what is known is that the novel virus originated in China, and in the initial phase, it did not fully recognize or communicate the deadly nature of the disease, creating concerns, whether fairly or unfairly, future.

China remains committed to a “zero Covid” strategy, this despite recent outbreaks and less-than-effective- homegrown vaccines. It shows no signs of modifying this zero-covid approach and has gone further with new strict lockdowns, in places wherever there is an outbreak, at whatever cost.

Recent research indicates all but 13 of China’s top 100 cities were implementing Covid restrictions, with ten cities in “severe lockdown”, with more than half of residents confined to their homes.

Whether China will continue its zero Covid strategy and provide accurate information on rates and locations of infections and deaths going forward if the number climb dramatically, is yet to be determined.

If this second Covid wave proves explosive, could it affect readiness and willingness to provide comprehensive information? Mere speculation, but if such were the case, with 1.4 billion people, the impact could be monumental on what we know about the reach of Covid.

We should not delude ourselves about how much we know where Covid cases are, and roughly how many people are infected or have died. Looking at past major pandemics such as the Spanish Flu, Cholera, and Black Death, each of which resulted in estimates in tens of millions of people dying.

Our present situation, thanks to technical progress, appears to us as deeply different – surely, we can’t imagine suffering to the same extent and proportionately witness the same massive numbers of deaths.

Yet, even with all our technological advances, there is no reason to feel confident that Covid will not have devastating impacts. We need to do better, to have improved tools and get a much firmer handle on data which in essence is based on robust health information systems.

This will mean adding now to the domestic and external investment mix, significant funding for health information—and treating it as a priority. This is not just for Covid today, but for future infectious disease outbreaks as well as the many other health challenges which can only be effectively dealt with if we know the scope of the problem.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — Featured Photo from Pixabay Visuals3Dd