Update 21 April 2020. A new study further confirms the link between the mortality rate of COVID-19 and air pollution. Carried out by Yaron Ogen, a scientist from the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg in Germany, it was just published in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

The study analyzed ESA satellite data on air pollution (NO2 levels) and air currents in Italy, France, Spain, and Germany with confirmed deaths related to COVID-19. There were 4443 fatalities in these countries due to COVID-19 by March 19, 2020. Most fatalities (83%) occurred in regions where NO2 levels were high. 15.5% of the fatalities occurred where pollution was “mid-level” and only 1.5% where it was considered low.

Update 9 April 2020. A new scientific study, just published in the United States, provides further proof that there may be a very real link between the speed of transmission and lethality of COVID-19 and air pollution. The study by researchers at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health in Boston, analyzed air pollution and COVID-19 deaths up to 4 April in 3,000 counties in the United States, covering 98% of the population. “We found that an increase of only 1μg/m3 in PM2.5 [particles] is associated with a 15% increase in the COVID-19 death rate,” the team concluded.

As noted in the UK Guardian, “A small increase in exposure to particle pollution over 15-20 years was already known to increase the risk of death from all causes, but the new work shows this increase is 20 times higher for COVID-19 deaths.” The study’s authors concluded: “It is likely that COVID-19 will be a part of our lives for quite a long time, despite our hope for a vaccine or treatment. In light of this, we should consider additional measures to protect ourselves from pollution exposure to reduce the COVID-19 death toll.”

To address COVID-19, it has become clear to the whole world that the Chinese model of testing strick social distancing is a must and that a full “lockdown” of the economy cannot be avoided – with only “essential” activities maintained. Italy was the first country to follow this Chinese model. Now, almost all countries have followed suit, including India with its 1.3 billion people told to stay home for 21 days – undoubtedly the largest quarantine operation in history. But there is another lesson from the Chinese and Italian experience that has emerged: the highly probable link between dirty air and level of lethality of COVID-19.

Greenpeace Italy’s director, Giuseppe Onufrio, an environmental activist with a physics degree from Bologna University, sounded the alarm five days ago in a well-researched article exploring the possible relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and air pollution.

He started by reminding us that biodiversity destruction, urbanization, and globalization trigger the well-known mechanism of “spillover” of new viruses from wild species to humans – something that was highlighted in a recent Impakter article by Richard Seifman calling for a “one health” approach to address pandemics, i.e. treating animal and human health as one. This is particularly relevant in COVID-19’s case that started in a market in Wuhan with the sale of wild meat.

Then Onufrio moved on to the main point:

The hypothesis that air pollution can act both as a vector of the infection and as a worsening factor of the health impact of the pandemic in progress has also been raised. Although it is still early to reach general conclusions, it is necessary to start clarifying another very important aspect of the relationship between viral epidemics and the environment. Or better yet, between human health and pollution/ environmental destruction.

Bologna University experts, including Professor Leonardo Setti who’s a specialist in supramolecular chemistry, in a recent “position paper” reported that they had found a correlation between days of exceeding the limits for PM10 in the control units of some cities and the number of admissions from COVID-19.

While the correlation is based on a very limited number of observations and therefore needs to be further verified, the underlying hypothesis – that fine particulate matter acts as a vector for other pollutants – is well known and certainly proven for other polluting factors such as for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs are released from burning coal, oil, gasoline, trash, tobacco, and wood).

Prof. Setti concludes:

“These analyzes, therefore, seem to demonstrate that, in relation to the period 10-29 February, high concentrations above the PM10 limit in some Provinces of Northern Italy may have exercised a boost action, that is, given an impulse to the virulent spread of the epidemic in the Po Valley that had not been observed in other areas of Italy that had cases of contagion in the same period (…) It is highlighted how the specificity of the rate of increase in cases of contagion that has affected in particular some areas of Northern Italy could be linked to the conditions of pollution by atmospheric particulates which exercised a carrier and boost action.”

An expert from the Italian National Research Center (CNR), Fabrizio Bianchi, head of the Unit of Environmental Epidemiology and Pathology Registers at the Institute of Clinical Physiology, who read Prof. Setti’s paper, was appreciative and commented that it was a valid “warning one could agree on”, even though “a more advanced study design” would be needed to take into account “the territorial inhomogeneity of the viral propagation time of the virus”.

China’s Experience with Air Pollution and Respiratory Diseases

China’s experience provides both valid and the world’s most extensive evidence to date that air pollution is associated with respiratory disease.

However, so far, relatively few studies have quantified the short-term effects of six major air pollutants on influenza-like illness (ILI – what most people call “seasonal influenza”). The latest study carried out in China was published in 2019 and explores the potential relationship between air pollutants and ILI in Jinan, China.

The study uses daily data on the concentration of pollutants and ILI counts from 2016 to 2017. A total of 81,459 ILI cases were collected, with the 0 to 4-year group reporting the most respiratory diseases and the 15 to 24-year group the least.

The methodology used in that study is consistent with the most exacting investigative criteria (inter alia, using wavelet coherence analysis and generalized Poisson additive regression model). The six pollutants considered were particulate matters PM 2.5 and PM10, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, and ozone. The effects of air pollutants on different age groups were also investigated.

The conclusion was stark: “Air pollutants, especially PM2.5, PM10, carbon monoxide, and sulfur dioxide, can increase the risk of ILI in Jinan.”

What happens is that excessive concentration of PM clearly makes people sick as the particles (to which the virus is attached) invade the lungs and weaken the capacity to resist respiratory diseases. In the words of the study:

“PM, a mixture of particles and droplets in the air, can raise the virus attachment to respiratory epithelial cells and deposit deep in the lung due to the small size and larger surface-to-volume ratio. Exposure to PM2.5 not only led to airway epithelial damage and barrier dysfunction but also decreased the ability of macrophages to phagocytize viruses, which raised the susceptibility of an individual to viruses.”

The study called on the Chinese government to “create regulatory policies to reduce the level of air pollutants and remind people to practice preventative and control measures to decrease the incidence of ILI on pollution days.”

But China went through an even more telling experience in 2002, when SARS ( severe acute respiratory syndrome), a coronavirus very similar to the one causing COVID-19, claimed 349 lives with 5,327 probable cases reported in mainland China. It was found that SARS case fatality had varied across geographical areas and an ecological study was made to verify the role played by varying levels of air pollution.

The study, published in 2003 was carried out by four American experts from the School of Public Health, UCLA (University of California at Los Angeles) and three Chinese experts, two from the Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Nanjing, and one from the School of Public Health, Fudan University.

The study found that mortality risk was amplified – about doubled – in areas with higher pollution than in those with better air quality. The conclusion is unavoidable:

“Our studies demonstrated a positive association between air pollution and SARS case fatality in Chinese population by utilizing publicly accessible data on SARS statistics and air pollution indices. Although ecologic fallacy and uncontrolled confounding effect might have biased the results, the possibility of a detrimental effect of air pollution on the prognosis of SARS patients deserves further investigation.”

Note the caveat: “the possibility of a detrimental effect of air pollution on the prognosis of SARS patients deserves further investigation.”

Given the closeness of the two viruses, it is clear that the detrimental effect of air pollution on COVID-19 patients also deserves further investigation. And the sooner, the better.

Europe’s Experience with the Deterioration of Air Quality

As the Greenpeace article points out, there is another aspect to consider. Air quality matters for good health: The presence of high concentrations of pollutants in the air is considered responsible for excess mortality. And this excess mortality happens in normal times when there is no pandemic of any kind anywhere. It also suggests that populations who live in highly polluted areas are at greater risk.

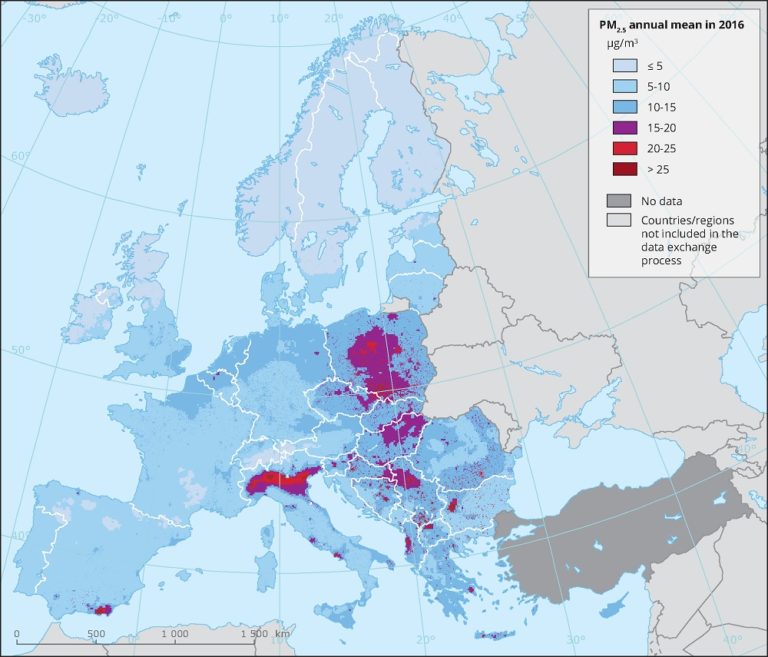

The European Environment Agency (EEA) has for some years now tracked air quality across Europe (latest report published in 2019) and focuses on excess mortality related to three environmental parameters, PM2.5, nitrogen dioxide, and ozone. The latest estimate for Italy (2016 data) reports a total of 76,200 deaths due to these parameters, most of them (approximately 77%) related to fine particulate matter (PM2.5).

If you look at the map of the EEA on the average concentration value of PM2.5 which shows areas that are particularly polluted (in red and deep purple), the situation of the Po valley stands out dramatically. But the Po valley is not alone: cities like Naples or Antwerp, countries like Poland, Hungary, and Serbia look just as bad as Northern Italy:

As the Greenpeace article put it:

“…the population in the Po Valley is more than others chronically exposed to high levels of air pollution and to the consequences that derive from it. And that is, therefore, likely to be one of the co-factors that aggravates the severity of the impact of a pandemic that attacks the respiratory system.”

Various factors contribute to this chronic situation that predisposes people to respiratory diseases, among them: a high concentration of industrial and zootechnical activities, high population density and therefore emissions from traffic and from heating city dwellings. Add to this unfavorable weather and climate conditions that can entrap smog over whole industrial areas and cities. The Po valley is famously engulfed in fog all winter long.

The above map also goes a long way to explain why (so far) COVID-19 has hit Northern Italy proportionately much more than Germany. That’s because Italy has done a bad job of controlling pollution while Germany did a good job.

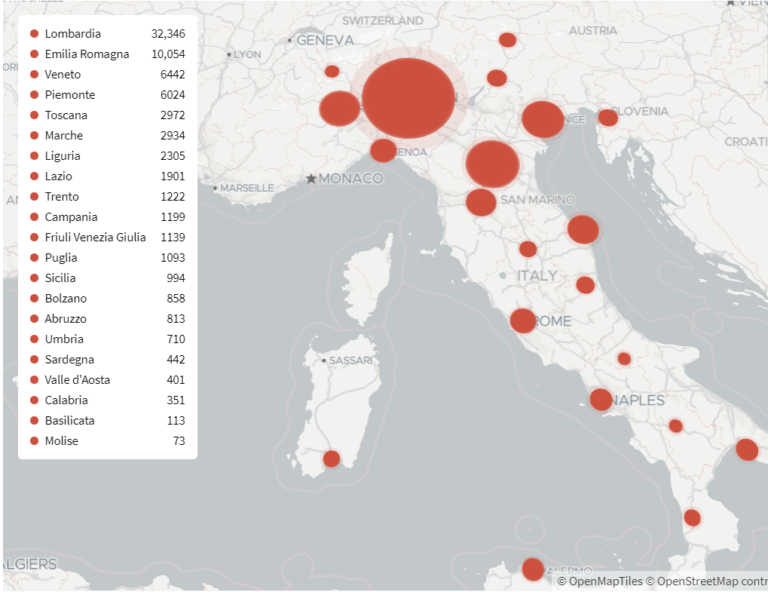

In fact, if you look at the impact of COVID-19 on Italian regions, you discover that the worst-hit areas are all those that suffer from high levels of air pollution due to largely unregulated industrial activities and urbanization:

Source: Gedi visuals situation on 26 March 2020

The above map clearly shows where the peak areas are, all in cities and industrial areas. By region, the only ones that escape the worst are those with famously clean air and relatively little industrial activity: Valle d’Aosta, Calabria, Basilicata, and Molise. Surprisingly perhaps, Sicily suffers from a high rate of contagion, but that is due to its two major industrial cities: Palermo and Catania (the latter not shown on this map).

If it turns out that air pollution is, in fact, a major factor in determining the extent and lethality of COVID-19, then heavily-polluted areas around the world should fear a particularly extensive and dangerous encounter with the virus.

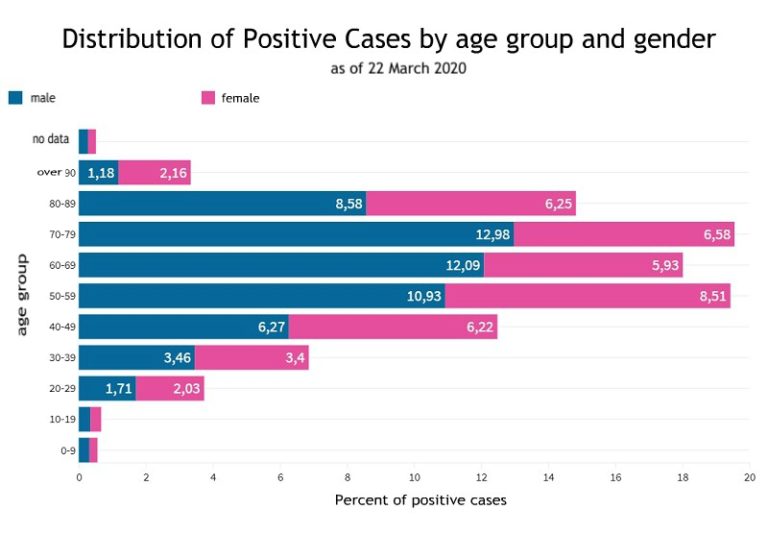

There are, of course, other well-known factors that influence COVID-19 morbidity, such as the share of smokers in the population. The Italian Health Institute (Istituto Superiore di Sanità) found (11 March 2020) that at the time of hospitalization, more than one-third of the COVID-19 patients who were smokers were in a “more serious clinical situation than non-smokers, and for them, the risk of needing intensive care and mechanical ventilation is more than double.”

Old people die more often from COVID-19 not just because they smoke, or have a heart condition or diabetes. They also die because they’ve been breathing polluted air for too long – polluted air that has deeply scratched their lungs and made them unable to resist the onslaught of the virus. To apportion blame among these various factors is, for now, impossible. But one thing is certain: the blame is there.

Source: Gedi visuals situation on 22 March 2020

This said, there is no question that air pollution is a major factor that needs to be taken into consideration. It is indisputable that chronic air pollution, with peaks of concentration of fine dust and other pollutants, is a worsening factor in cases of epidemics. Air pollution acts in two ways: as a vehicle that amplifies the spread of the virus and as a chronic stress factor that makes the population more vulnerable to an epidemic, even if it is not possible, as in the Italian case, to establish by how much.

Greenpeace sees air pollution as an additional reason to pursue their campaigns to promote “sustainable mobility, exit the era of fossil fuels, stop diesel, reduce the production of intensive farms”, all seen as important sources of primary or secondary particulate matter.

In other words, the fight against COVID-19 is linked to the fight against air pollution. And environmental degradation. Ultimately it is the same as fighting against climate change.

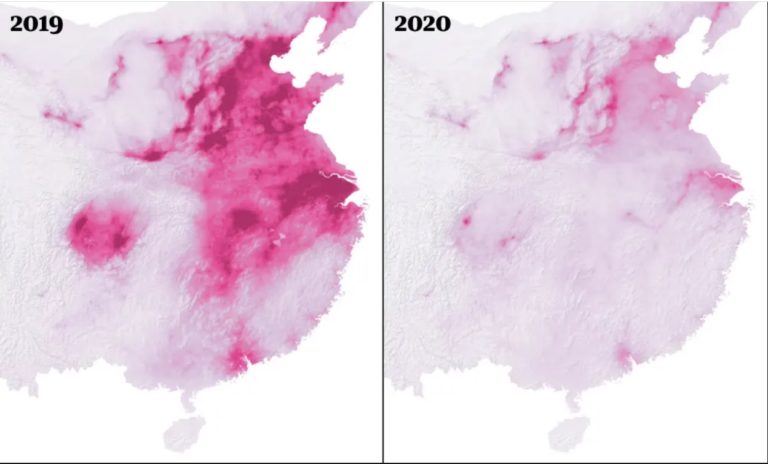

A word of warning to avoid confusion. The coronavirus pandemic has, for now, caused a huge drop in air pollution around the world, and especially in the more polluted areas of China and Italy. Is that good? The problem is that it’s temporary. The reason is obvious: A direct consequence of the economic lockdown.

Satellite images, reports the UK Guardian, reveal a remarkable fall in global nitrogen dioxide levels. For example, here are ESA satellite images showing pollution levels in China before (in 2019) and after the lockdown (in 2020 – both in red, see below).

As the Guardian article explains, “nitrogen dioxide is produced from car engines, power plants, and other industrial processes and is thought to exacerbate respiratory illnesses such as asthma.” While it’s not the same as a greenhouse gas, it has the same origin: in the industrial activities that are “responsible for a large share of the world’s carbon emissions and that drive global heating.”

Pollution levels in China in 2019, left, and 2020. Photograph: Guardian Visuals / ESA satellite data

A temporary drop in pollution – and hence, better air quality for now – no doubt has a health effect and helps populations to fight the spread of COVID-19. As Monks, the former chair of the UK government’s science advisory committee on air quality noted, a reduction in air pollution could bring “some health benefits, though they were unlikely to offset the loss of life from the disease”.

But that is not the problem. The problem is chronic and high levels of air pollution. That is what predisposes people to fall prey to this coronavirus – and before COVID-19, to SARS.

A short while ago, what looked like two separate battles, one against climate change to save the planet, the other to prepare better for pandemics via a one health solution, is really just one battle:

What saves the planet will save our health.

If you want to know what a good coronavirus strategy looks like, check this article that lays out “the hammer and the dance” – and suggests a strategy that could save millions. And sign the petition to the White House. No government should be allowed to take COVID-19 lightly.

But in the long run, the battle is different.

Because pandemics like COVID-19 will return. And all (or most) of them linked to our collapsing environment. We need to fight the virus with good strategies for now, and for the future, we need good prevention measures. And the first prevention is to clean up the air we breathe.

Let’s remember that when the current COVID-19 crisis is over.

Featured Image: Factories beside a body of water CC0 Pikrepo

.