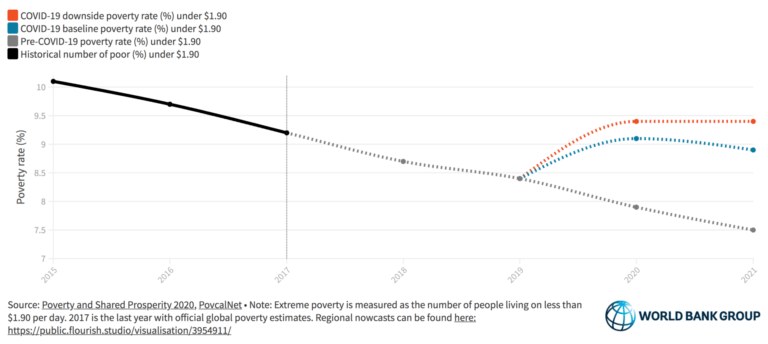

Defined as living on less than US$1.90 per day, extreme poverty has decreased globally from over 35% in 1990 to 8.4% in 2019. Until COVID-19, the global poverty rate was projected to drop to 7.9% in 2020.

Instead, the World Bank’s report “Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune” now estimates that the rate will rise to 9.1-9.4% in 2020 and that it would be about 7% in 2030 (which the report notes is an optimistic projection).

This is a huge hindrance to global development progress and poverty reduction as well as to the UN Sustainable Development Goal 1 to end poverty in all its forms everywhere by 2030. “In order to reverse this serious setback,” said World Bank Group President David Malpass, “countries will need to prepare for a different economy post-COVID, by allowing capital, labor, skills, and innovation to move into new businesses and sectors.”

Approximately 80% of the “new poor” — 72 million people — will be from middle-income countries.

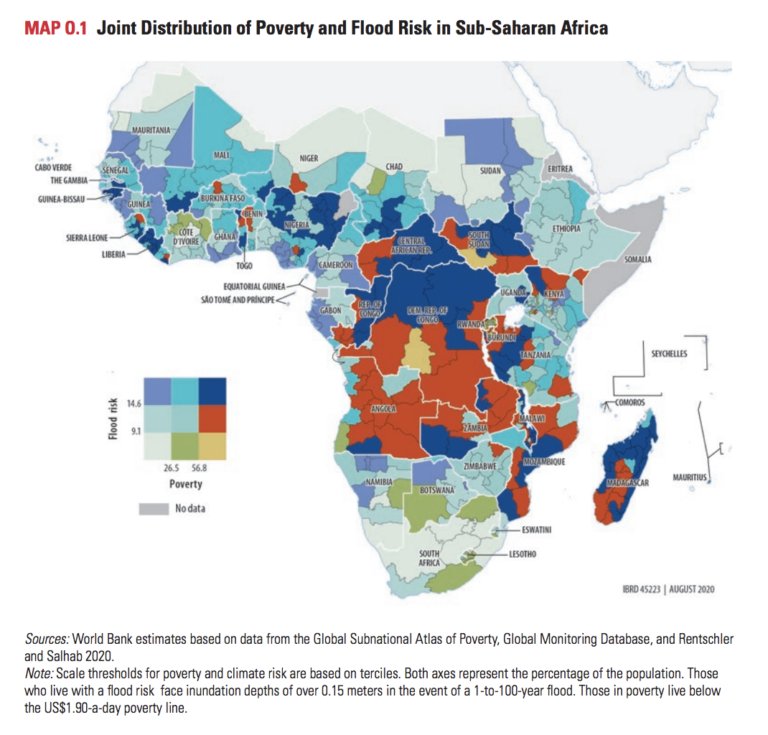

This issue, intensified by climate vulnerability and armed conflict, is not restricted to countries that already have high poverty rates. Approximately 80% of the “new poor” — 72 million people — will be from middle-income countries like India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Nigeria. In terms of regions, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa are expected to have the highest number of people pushed into extreme poverty. Both of these regions have high flood risks, with armed conflict prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Conflict stricken nations have difficulty maintaining wealth because of loss of human capital, gaps in education and conflict debt. When that converges with climate crises and the pandemic, the economic effects can be catastrophic.

In addition to an increase in extreme poverty, shared prosperity — the increase in wealth of the poorest 40% of a country — is expected to decrease across most economies over the next two years. This decline will deepen income inequality and decrease job prospects among those with basic education.

The report also outlines heightened difficulty in obtaining a basic education. Several countries expect loss of human capital in disadvantaged households, meaning there will be people who are inhibited nutritionally and kept from getting an education. In a phone survey to seven countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, 40% of respondents reported running out of food during the COVID-19 lockdown. This lack of nutrition will continue to cause delays in children’s health, cognitive development and future human capital accumulation.

In 2020 and 2021, there are expected to be millions of “new poor” who are not employed in agricultural fields and live in urban settings.

The profile of people experiencing these issues is changing because of COVID-19. In 2020 and 2021, there are expected to be millions of “new poor” who are not employed in agricultural fields and live in urban settings. This differs from the typical profile of poverty, which is predominantly made up of people living in rural areas with agricultural jobs.

But even though the profile of the poor is being diversified, the poorest and most vulnerable people before the pandemic are being hit the hardest. This includes people who have escaped or nearly escaped poverty as is seen in Sub-Saharan Africa, a region expected to see one of the largest growths in “new poor,” just after South Asia, with as many as 40 million people being pushed to live under US$1.90 per day.

Related Articles: How Higher Ed Can Help | COVID Infodemic

Children are also experiencing immense impacts of the COVID-19 crisis, according to UNICEF and Save the Children’s report “Impact of COVID-19 on multidimensional child poverty” that measures poverty multidimensionally and takes factors other than finances into account. Their analysis, which includes the lack of access to education, proper nutrition and clean water, reported that the rate of children living in multidimensional poverty has risen from 47% to 56% since COVID-19 — that is 150 million additional children. The report also describes that it is not just “new poor.” The poorest children are getting poorer.

Unless serious changes are made, the World Bank report warns, the pandemic and resulting economic crisis could leave lasting scars on countries worldwide. The worry is that without action the crisis will create cycles of income inequality, decrease social mobility of the most vulnerable and erase resilience to future shocks.

The World Bank, UNICEF and Save the Children are calling for fast action. Policy changes and protective social programs need to be put in place to help the newly impoverished people in addition to those who were already vulnerable before the pandemic.

The Poverty and Prosperity report emphasizes the need to design policies that are targeted for the “new poor,” with focuses on creating safety nets, measurements to rebuild jobs and plans to strengthen human capital, calling for research to be directed at specific areas where COVID-19, climate change and armed conflict meet.

Without swift and steady action, the effects of the economic crisis caused by COVID-19 threaten to dismantle decades of progress in poverty reduction.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Habiba Suleiman (28) a District Malaria Surveillance Officer (DMSO) in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Featured Photo Credit: USAID U.S. Agency for International Development