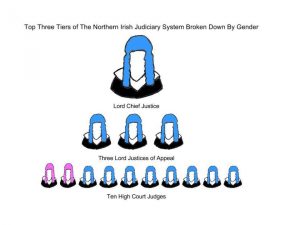

The disproportionate number of male judges in the United Kingdom is highlighted nowhere more so than in Northern Ireland. The Lord Chief Justice is a man, as are the three Lord Justices of Appeal. Out of the ten high court judges, eight of them are men, meaning in the top three tiers of the judiciary in Northern Ireland, there are only two women in total. In the Republic of Ireland, there is still a gender disparity between male and female judges but there is less of a shocking contrast.The position of Chief Justice is occupied by a woman and 37.5% of Supreme Court judges are female; although, this is far from achieving equality, not to mention that the majority of senior judges in both Ireland and Northern Ireland are white and cis-gendered.

Questioning both the lack of diversity amongst judges and the impact of having more female judges is one of the goals of the Northern/Irish Feminist Judgements Project.

In The Photo: Diagram showing the gender of Northern Ireland’s senior judges Photo Credit: Rebecca Anderson

A Feminist Judgements Project is a coming together of feminist legal scholars and professionals who rewrite court rulings, which have been fundamental to shaping legal tradition, in order to create the missing feminist judgement. Interestingly, writers of feminist judgements must adhere to the same legal constraints of precedent and custom as the original judge and can only use material that would have been available at the time of the hearing.

There are multiple goals here: firstly, Judgement Projects show that the law and feminism are concepts which can work in harmony. Secondly, there is often a gap between feminist legal theory and the rest of feminist theory, partly due to the former’s abstract nature. Feminist Judgement Projects are an opportunity for feminist legal scholars to show, to both the legal and the feminist community, just how feminist legal theory can be put into practice.

Feminist Judgement Projects are creating transnational links and communities as the first Feminist Judgements project in the United Kingdom was inspired by the Women’s Court of Canada. The Northern/Irish Feminist Judgements Project began in 2014 and took place over four drafting workshops involving academics from both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. The rewritten judgements will be collected and published as a book later this year which, fittingly, will open with a poem that reads like a battle cry by Sarah Clancy. Northern/Irish have brought an exciting new methodology into play. Their project is not solely focused on the masculine nature of the legal voice but also on how the figure of the judge is part of a wider governmental identity project. Throughout their project they, controversially, view the judge as a political actor and seek to interrogate how judges use the courtroom and their rulings to shape national identity.

Related articles: “SDG 5: ACHIEVING GENDER EQUALITY”

The Northern/Irish Feminist Judgements Project highlights two things.

Firstly, having a range of judges from different backgrounds would diversify the outcome of legal rulings, and secondly, that neither the law or judges are as neutral parties. In rewriting judgements, Feminist Judgement Projects highlight that the law can be interpreted in different ways. Thus, showing that there is not just one way to read the law which means that a choice is made by each judge as to how they want to interpret the law.

At times though, even within Feminist Judgement Projects, judges are unable to reach the outcome they would consider to be the most feminist due to the fact that they are under the constraints of custom and precedent. This shows that the law does not offer justice or equality to everyone.

This is particularly relevant in the context of Northern Ireland where women are not offered the same reproductive rights as elsewhere in the United Kingdom as abortion is almost completely illegal. Furthermore, Northern Ireland is also the only part of the United Kingdom where same sex marriage is illegal.

The Northern/Irish project attempts to lead legal reform from within by de-centering the voice of the male judge and replacing it with the feminist concepts of equality, community and tolerance. By working within the constraints of the law, the project is able to reclaim the legal narrative as a democratic space which is open to all.

But reclaiming the legal voice is not the only goal here. The project also wants to draw attention to feminist contributions to judicial studies in Ireland and start to create a body of feminist judgements which can be used to train future legal professionals.

As Northern Irish and Southern Irish legal professionals and activists worked together, the project also consolidates a feminist legal studies network across Ireland with hopes that this will lead to further cross-border collaboration. The legal landscape on both sides of the Irish border has been shaped by a legacy of violence which has resulted in “difficult and overlapping legal and political histories”. Further cross-border collaboration can provide countless tools for legal activists, academics, professionals and politicians.

In the photo: Scales weighing the signs for masculinity and femininity Photo Credit: Pixabay/GDJ

Not all feminists would be advocates of Feminist Judgements Projects.

Audre Lorde once famously wrote that the “master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change”. In other words, considering that historically legal discourse has been dominated by men, it will never be able to re-appropriated enough in order to fit the needs of women. However, Lorde goes on to say that “this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support”.

Feminist Judgement Projects do not only define the master’s house, legal discourse in this case, as their only source of support as they also, obviously, heavily draw on feminist theories. If anything, by marrying feminist legal theory with the current legal discourse they subvert the master’s house from the inside which will force it to change.

For a full mindmap containing additional related articles and photos, visit #FeministJudgements

It could also be argued that it will be difficult for Feminist Judgements Projects to attract the attention of those outside of the feminist legal community. It might be more effective to lead a feminist reform project that challenges the law from a mainstream platform.

However, while these critiques should be taken on board, there is something which is sacrificed in order to confront law on its own terms, from within legal scholarship. Furthermore, the Northern/Irish Feminist Judgements Project actually mixes judgement writing with other mediums such as poetry. By subverting the traditional legal narrative in this way, creating a book, hosting public events, having an accessible website and social media presence, their project does engage with its audience using mainstream channels.

They also seek to make the project more accessible by providing a host of resources on their website, including recorded lectures, historical background to the cases and articles, which give anyone interested in the project the opportunity to find out more.

It is also important to consider that a feminist legal project opens itself up to more critiques- those from the feminist community and those from the legal community. Feminist Judgements Projects can be tools of empowerment that use feminist networks and collaboration to encourage women already in the legal world and let them know that they are not alone or inspire those preparing to join the legal profession.

We can’t go back in time and change past judgements but what we can do is use feminist collaboration in order to try and stop the same mistakes happening again.

Feminist Judgement Projects are exciting for lots of reasons, they are great educational tools and raise questions about the nature of judging, but above all, what can be more empowering than reclaiming a narrative which has historically excluded the voices of women?

Recommended reading: “FEMINIST JUDGEMENTS: AMENDING HISTORY“