Sometimes it helps to take a step back and consider a pandemic in its overall public health context. COVID has occupied our minds – of scientists as well as all of us, the potential and actual victims of the virus to the point that we risk not seeing the forest for the trees. But to place COVID in perspective in relation to all the other important diseases that have preyed on humanity and still affect it, from chickenpox to tuberculosis, makes it easier to assess where we stand. We see better what we have done right in the light of past experience and what needs to be done to move forward. This is what this article will (modestly) attempt to do.

The COVID situation now, still rising with the 4th wave in Europe

COVID-19 has swept much of the world, and, as of late November 2021, well over five million people have died from it. This is the death toll announced by the Worldometer on November 24, 2021(screenshot):

Countries have been experiencing wave after wave of COVID infections, whether from the Delta or other variants. In the United States, COVID cases have surged about 30 percent in November, despite prediction models of a continuing decline. Here are the New York Times tracking results for the US in the last 90 days (screenshot):

Countries have been experiencing wave after wave of COVID infections, whether from the Delta or other variants. In the United States, COVID cases have surged about 30 percent in November, despite prediction models of a continuing decline. Here are the New York Times tracking results for the US in the last 90 days (screenshot):

In the European Union, rising contagion averages have quadrupled in recent weeks, driven by the Delta variant and a large number of unvaccinated in several countries, including Germany.

Many of its governments are now looking at containment options ranging from outdoor/indoor mask requirements to limiting unvaccinated people from public life to partial lockdowns in France, Germany, and Italy, and to Austria which is already in full mandated lockdown. These measures are being taken despite existing or expected public protests.

Further, some scientifically sophisticated countries have begun considering conditional preparations for a “doomsday variant.” Experts in Israel have warned the government that there are signs that as the Delta variant is waning and with a fifth COVID wave looming, a vaccine rollout to cover children will not be enough to contain it.

A look at past experience with vaccination and preventive measures

Historically we have largely been able to vaccinate our way out of many widespread infections, including chickenpox, diphtheria, measles, mumps, polio, rabies, rubella, smallpox, tetanus, typhoid, whooping cough, yellow fever.

Even in the last four decades when faced with the “new” HIV/AIDS pandemic, we have done reasonably well with the advent of medications and preventive measures, with AIDS-related deaths falling from 2 million people at its peak to roughly 680,000 people in 2020. (Note: there is still no vaccine for HIV/AIDS).

Surprisingly, Sub-Saharan Africa is where HIV/AIDS originated and historically the most devastated region from communicable diseases, it seems to have been able to avoid the worst COVID impacts so far.

Wafaa El-Sadr, chair of global health at Columbia University notes that “Africa doesn’t have the vaccines and the resources to fight COVID-19 that they have in Europe and the U.S., but somehow they seem to be doing better”.

However, as Dr. Michael Osterholm, a noted epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota, put it, “We still are really in the cave ages in terms of understanding how viruses emerge, how they spread, how they start and stop, why they do what they do.”

Where COVID-19 has been in some ways unique is in unprecedented worldwide health data coordination and research. It has meant intensive resources by and from the science community, governments, financial and health institutions, and citizens. A European study published in January 2021 found that in the first 11 months of the pandemic, over $93 billion was poured by the public sector into COVID research, more than in any other disease – with 95% into vaccines and only 5% in therapeutics.

As a result, we have new mRNA and viral vector vaccination technologies and treatment options such as monoclonal antibodies for COVID. This is enormously positive and augurs potentially well for the future. Yet we are far from any comfort level in dealing with this virus.

In assessing where we stand, it is important to keep in mind COVID’s extensive negative effects, beyond those infected by the virus. It has had major indirect “knockdown effects” in multiple ways, including affecting those with existing autoimmune, heart disease, and other pre-existing conditions; placing enormous burdens on health services less able to attend to other conventional causes of morbidity and mortality; creating fears of visiting health facilities; and dampening efforts at other health preventive measures.

COVID is appropriately described as a killer communicable disease, but there are deadly others that have plagued the world for centuries, and now primarily developing countries, and they have not benefited from such levels of intensive and sustained attention as COVID is receiving.

Here are examples:

Malaria is one of the oldest and most intractable. In 2019, there was an estimated 229 million cases and over 400,000 deaths worldwide, with over 90% in the WHO Africa Region. No widely tested and approved vaccine exists, but there are signs of a breakthrough, as major COVID vaccine producers which use the RNA messenger technique (mRNA) have been moving forward for malaria and garnering WHO advisory approval.

Tuberculosis (TB) is another communicable disease from time immemorial. One million and a half people died from TB in 2020 with an estimated 10 million people falling ill from existing and new strains of TB.

In sum, health threats, are very different between countries, especially in terms of communicable and non-communicable disease risks. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDCs) capture many factors directly or indirectly affecting health circumstances, and they are complex.

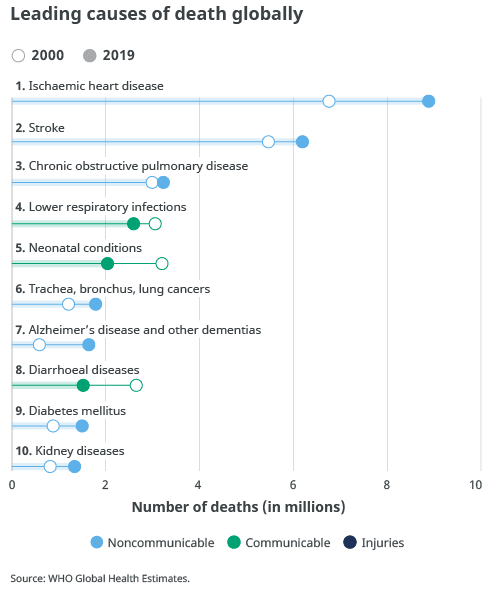

A shortcut and useful tool in understanding these differences is the World Health Organization (WHO) use of the World Bank classifications of world economies into four income groups, based on gross national income – low, lower-middle, upper-middle, and high. Detailed data and graphs are provided by WHO in its top 10 causes of death, with the global aggregated picture below:

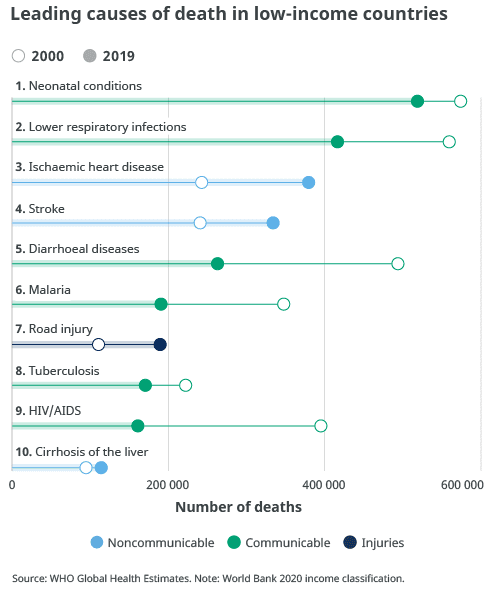

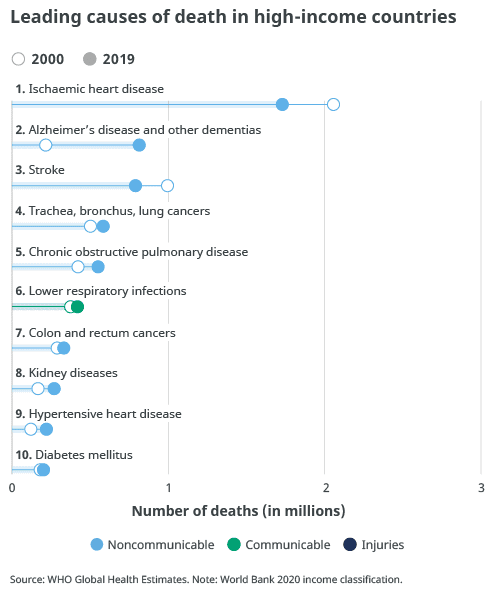

But the picture is very different when you look at these leading causes by economic classification:

- low-income countries: Four of the ten leading causes of death are communicable diseases. Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases are infrequent in these countries compared to other income groups, especially the upper-income cohorts.

- lower-middle-income countries: Two of its ten leading causes of death are communicable diseases, with diabetes a rising cause of death, and big increases in deaths from cardiovascular disease.

- upper-middle-income countries: Only one communicable disease, lower respiratory infections, is in the top 10 causes of death. Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause. Lung cancer and stomach cancer begin to feature importantly for this group.

- high-income countries: As with upper-middle-income countries, cardiovascular disease is the highest cause of death and there is only one communicable disease that is in the top 10 causes of death. Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, stroke, appear as leading causes of death, as well as lung cancers.

What Does This Tell Us?

Health risks differ widely in terms of what can be done individually and collectively to reduce risks. Known communicable diseases remain among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality for many populations in lower-income countries and regions.

The point is not to diminish the focus on COVID, as it certainly requires continuing intensive effort going forward, but it is also true that “old” communicable health threats must be a critical priority and given greater attention.

Global coordinated efforts show that innovation, cooperation, financial and technical assistance contributions can help begin to deal with the uncharted COVID pandemic. We need to bring more of this cooperative science effort, financing, and public awareness, this “can do” approach, to address communicable diseases which mostly affect vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Vaccine protests at Barclays in Brooklyn N.Y. April 7, 2021, Photo by Felton Davis, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons