ENVIRONMENTAL DESTRUCTION (PART TWO)

This is the second of a two-part article investigating cocaine. Part One surveyed the cost in human terms, focusing on Colombia, the world’s top coca producer (see here). Part Two investigates the environmental destruction caused by cocaine and also takes a look at Peru.

Uncle Sam’s fumigation program in Colombia has added a grim dimension to the environmental devastation that is, in any case, inherent to coca production when it is made illegal. When coca fields are mechanically torn up by the army or the police, farmers are pushed deeper and deeper into the jungle to clear more areas to grow coca along with the food needed for their own sustenance.

In the Photo: rainforest Photo Source: Anahi Martinez on Unsplash

But when coca fields are sprayed with potent herbicides, fumigation turns the fertile earth into a desert, threatening local farmers’ health. In fact, for decades, Colombia has been the only government in the world that has allowed aerial herbicide spraying of coca, hurting its own population. But it did so at the bidding of the United States that ended up paying US$ 2 billion for the spraying.

An extraordinary cost to the American taxpayers with zero results in terms of reduced cocaine supplies.

It had, however, very measurable results in terms of environmental destruction of Colombia’s rainforests – precious not just for Colombia but for the whole world, as they act as major carbon sinks, playing a key role in stabilizing global climate.

It is hard to decide which is worse for the environment: coca cultivation (as promoted by drug traffickers and all rebel groups active in Colombia since the start of the “Violenza” in 1948) or the aerial spraying of herbicides containing glyphosate (a program that began in 1994 with Bill Clinton’s approval). It was finally suspended on May 9, 2015, by Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos, alleging public health reasons.

That was back in 2015. Today, there’s a pushback with a surprising number of scientists arguing that glyphosate is not, in fact, bad for human health. Should we believe them?

How dangerous is glyphosate for human health?

When a 2015 study, carried out by International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a semi-autonomous think tank and investigative arm of the World Health Organization, classified the weed killer glyphosate “as probably carcinogenic to humans”, there was a bizarre reaction in the scientific community, with many openly and loudly expressing disbelief in the IARC’s findings.

In the Photo: farmer’s hands. Photo Source: Eddie Kopp on Unsplash

For an outsider (as I am), it is difficult to fathom why a WHO report would be denigrated by scientists, but that is what happened. When scientists are willing to say that glyphosate does not cause cancer, implying that it is innocuous for farmers handling it (and for those consuming products that have been sprayed), many people raised eyebrows in disbelief. Are scientists in the pay of the herbicide industry? Of course not, right? Still, one cannot help but wonder what is really going on.

Setting aside any doubts we may have in this regard, here are the few facts that nobody disputes.

Glyphosate is the most heavily used herbicide in the world and happens to be a key ingredient in Monsanto’s bestselling RoundUp brand. While no longer under patent, Monsanto still makes a lot of money from selling genetically-modified crops that are resistant to the glyphosate in RoundUp.

Most recently (June 2017), Reuters, in an investigative report on the “glyphosate battle”, said that Aaron Blair, a US National Cancer Institute (NCI) epidemiologist that had chaired the 2015 IARC study I mentioned above, had serious personal doubts. At the time, he had been aware of the results of unpublished NCI research arising from a multi-year study of some 89,000 agricultural workers in the US that seemed to prove there was no link between glyphosate and cancer. Yet, for some unexplained reason, he refrained from bringing up the matter with his IARC colleagues.

Now Mr Blair has done so, pointing to the NCI research in a testimony he recently gave in an on-going legal case in California against Monsanto, brought by 184 plaintiffs who claimed that exposure to RoundUp had given them cancer. IARC remained indifferent. It told Reuters that, “despite the existence of fresh data about glyphosate, it was sticking with its findings” and that it had “no plans to reconsider” its assessment.

It should be noted that the NCI research is unpublished and therefore still awaiting the test of peer review and independent evaluation. Yet, Monsanto has no doubts:

Scott Partridge, Monsanto’s vice president of strategy, told Reuters the IARC glyphosate review “ignored multiple years of additional data from the largest and most comprehensive study on farmer exposure to pesticides and cancer.”

Who to believe? Major regulatory food authorities around the world, including the very cautious European Food Safety Authority, have kept glyphosate under review since the 1980s and concluded it is “unlikely to cause cancer in humans”. It went so far as to declare it “safe” in June 2017 but left many people dissatisfied as it looked like it had “copied” Monsanto’s study. Some argued that this called into question the entire European review process, but, as the Reuters report points out, it’s “not settled science”.

The European Commission recommended that the license for glyphosate be renewed for ten years, but on October 24, the European Parliament voted to ban it by 2022, adding pressure on the Commission, amid the escalating row over whether Monsanto “unduly influenced” research into its weedkiller.

There is, however, another aspect to this controversy that nobody dares to dispute: the impact of coca production on the environment.

Coca-related environmental damage

The spraying of herbicides over coca crops in Colombia over a period of 21 years has turned 4.35 million acres as bare as the surface of the moon. That’s an area the size of Connecticut plus much of Rhode Island. As a result, local farmers are displaced and forced to burn down more of the rainforest around them to grow food crops to survive, as well as coca crops to make money because there is no way out: this is the only cash crop available to them.

In short, the fumigation program has been a total failure. Whether it has or has not affected the local population’s health, one thing is certain: it has stimulated the continuous expansion of coca crops into Colombia’s rainforests. There was a dip in production around 2010, temporarily putting Colombia behind Peru in the classification of coca-producing countries, but since then production has rebounded and it is now higher than ever.

Environmental damage is not limited to Colombia, but it appears in Peru and Bolivia as well. Aerial spraying of herbicides is only part of the problem. It makes a thoroughly bad situation worse.

The dynamics of coca production and the fallout on the environment are at the heart of the matter.

We’ve known for a good while now that this is a serious problem. As early as in 1992, M. Dourojeanni, a professor at the National Agrarian University in Lima, Peru and Chief of the Environmental Protection Division at the Inter-American Development Bank, provided what is still today considered a classic report on the environmental impact of coca production. He did this at a time when little or nothing had been written about the environmental damage caused by coca cultivation and the process of producing basic coca paste. He was among the first to pull together what we know now as overwhelming evidence of the dramatic impact that both activities have on the ecosystems in which they are carried out.

His study focused on the situation in the Upper Huallaga Basin, a primary illegal coca growing area in Peru since the 1980s, though legal coca has been cultivated there for thousands of years. Coca leaves are traditionally consumed in the region and archaeologists have uncovered Peruvian foraging societies that chewed coca leaves 8,000 years ago. But what drew Professor Dourojeanni’s attention was that “the illegal cultivation of coca is almost 10 times greater than is the legal, and that it is by far the most widely grown crop in the Peruvian Amazon region”.

The deforested land is not only used by coca producers, he noted, it is also “land on which landing strips (of which more than 100 exist at any one time), laboratories and camp-sites are built.” What makes coca cultivation particularly toxic for the environment is that farmers, in their search for the highest yields possible, apply commercial agrochemical substances “in such large quantities as to reach the visible limits of phytotoxicity”.

But adverse effects don’t stop at the edge of the coca fields. All these substances flow into nearby rivers, where they affect marine life.

More recently, a study conducted in Colombia showed that, on the basis of 2008 data from the Antinarcotics Office of the Colombian Police and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), two to three hectares of forest need to be cleared to establish one productive hectare of coca.

The dynamic is clear: as police and army forces destroy coca fields, farmers are pushed into the forest and clear the area they need to rebuild their homes and grow food in addition to the coca that is the source of their livelihood.

In the photo: Anti-narcotic police officers destroy a cocaine laboratory in Llorente, Colombia, Wednesday, July 29, 2009. Four laboratories were dismantled in Narino state. Source: AP Photo – Boston.com article on 2009 UN World Drug Report.

In the photo: Anti-narcotic police officers destroy a cocaine laboratory in Llorente, Colombia, Wednesday, July 29, 2009. Four laboratories were dismantled in Narino state. Source: AP Photo – Boston.com article on 2009 UN World Drug Report.

It gets worse: the preparation of basic cocaine paste has an incomparably greater impact on the environment than the agrochemicals used by farmers.

During the process air, soil and water are contaminated. Smoke pollutes the air when the coca leaves are dried in wood-burning stoves, the wood for which is obtained from the little forest that remains. To compound everything, farmers throw out the ash residues from the stoves and purchase commercial fertilizers.

Overall, the coca production process causes soil erosion which washes tons of sediment into local river systems, threatening marine life. The processing of the coca leaves to extract alkaloids, using substances like alcohol, benzene, sulphuric acid, carbide and kerosene, as well as sodium carbonate to precipitate the raw cocaine, contaminates not only the soil but also water. It is known that kerosene, although moderately toxic, severely affects the biology of water flora and fauna, especially plankton.

Less fish are available, many fish become unsuitable for consumption, and the quality of potable and irrigation water is threatened.

The law breakdown threatens natural reserves

Ultimately, it is not just a matter of deforestation. Coca-producing areas are “lands without laws”, to which public officials have no access. The exploitation of forests, game and fishing is completely anarchistic. The few protected natural reserves that exist in that part of the world are at risk of extinction.

Dourojeanni wrote of the numerous natural parks that were invaded by coca producers in 1992 when he did his research: the Manu National Park (Madre de Dios and Cuzco), the Tingo Maria National Park, the Abiseo National Park and Yanachaga-Chemellen (Pasco) National Park. He noted that at least two national forests had been partially invaded by coca producers: Alexander Von Humboldt Park and Apurimac Park.

The situation is infinitely worse today, particularly in VRAEM, the valley of the three rivers Apurimac, Ene and Mantaro, known as Peru’s “cocaine valley”, the area that includes Apurimac Park. As to the Madre de Dios region, it is suffering from the additional damage brought about by a decades-long illegal gold mining boom, causing a “mercury epidemic” as many miners use mercury to extract gold from sediments. The mercury then flows into the rivers and contaminates fish. In 2016, Peruvian authorities even declared a 60-day public health emergency to try and address the issue, an attempt deemed “pathetic” by the press, as deforestation proceeds unimpeded.

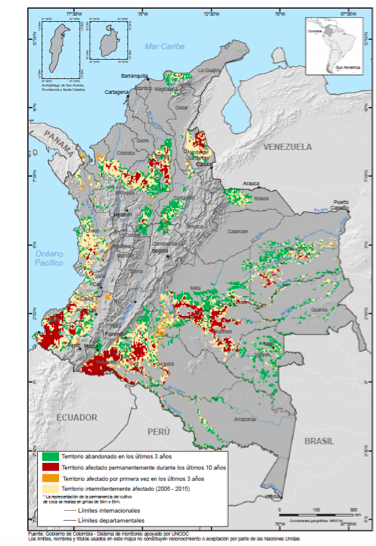

Tallying the hidden environmental cost of coca production is difficult, but some have tried, notably the Stockholm-based Institute for Policy and Development, citing a UNODC 2011 estimate that in Peru 2.5 million hectares of the Amazon forest have been destroyed to grow illicit coca crops. UNODC has also been regularly monitoring the environmental damage in Colombia, confirming its prevalence and persistence through time.

In the photo: Prevalence and persistence of coca cultivation 2006-2015 in Colombia. Source: UNODC

In the photo: Prevalence and persistence of coca cultivation 2006-2015 in Colombia. Source: UNODC

As recent studies, such as one from the Open Society Foundation published in 2015, point out, there is little doubt that current “drug control policies perversely harm the natural environment” and “drug crop eradication drives deforestation”.

Policies to disrupt and intercept drug shipments not only drive forest loss and habitat destruction but push drug traffickers to seek out new routes, often through fragile, biodiverse frontier regions.

Drug prohibition and the inevitable illegal markets associated with it earn traffickers grossly inflated profits that they then launder around trafficking hubs in frontier areas. They engage in ranching, logging, and agribusiness ventures, among other activities, that add to the general environmental destruction. Such booming frontier towns are a common sight in Colombia.

SEE RELATED ARTICLES: COCAINE: THE HIDDEN COST (PART 1)

Conclusion: Developed countries need to curb cocaine consumption

All experts agree that the environmental devastation resulting from such policies “is trade-driven, i.e. correlated to demand for a commodity rather than rural poverty”. In other words, it is the demand for cocaine in developed countries, especially in the United States and Europe, that is the root cause of the problem.

The time has arrived for the US to abandon its “war on drugs” waged in Colombia and other areas where coca is produced, and to focus on curbing cocaine consumption at home.

At the international level, the message is clear: Since the adoption by the UN General Assembly (UNGA) in 2013 of the United Nations Guiding Principles on Alternative Development, the UNGA has reaffirmed its commitment with a new Resolution in 2016 whereby several major UN agencies, among them the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the International Labour Organization, the United Nations Development Programme and others are tasked to “fight environmental destruction and improve farmers’ incomes” with “comprehensive and sustainable alternative development programmes, including preventive alternative development.”

There is only one problem: what exactly is a workable “alternative development programme”?

The language of the document is long on good intentions and short on practicalities. It states that alternative development programmes “should include measures to protect the environment at the local level, according to national and international law and policies, through the provision of incentives for conservation, proper education and awareness programmes so that the local communities can improve and preserve their livelihoods and mitigate negative environmental impacts.”

We can all agree that local involvement is key but will education and raising awareness do the trick? Certainly what is required is a combination of “local wisdom, indigenous knowledge, public-private partnerships and available resources” hopefully to promote, inter alia, “a legal market-driven product development approach when applicable, capacity-building, skills training of the involved population, effective management and the entrepreneurial spirit, in order to support the creation of internal and sustainable commercial systems and a viable value chain at the local level, when applicable.” A mouthful that says little.

Clearly, what will be needed in Colombia and other coca-producing countries are economic solutions that ensure a decent livelihood to farmers who abandon coca production.

Colombia’s ambitious new plan for 2017 – aiming to eradicate 100,000 hectares of coca crops by year end – has already been declared a failure by July. As noted by Insight Crime that follows the situation closely, the plan from its inception faced “old obstacles”, essentially because it relied on worn-out methods that don’t work: forced crop eradication by the army over 50,000 hectares (pushing farmers further in the forest), and offering no viable economic alternative for the other 50,000 hectares. Farmers were told to grow coffee or cacao, the obvious legal crops in Colombia’s rural environment.

In the Photo: cocoa beans Photo Source: Pablo Merchán Montes on Unsplash

The problem is always the same: coffee and cacao are not competitive with coca. The only solution is to cut demand for coca so that prices will fall to a point where coffee and cacao become economically viable.

Eradicating demand will work far better than eradicating supply. And that means developed countries should turn to policies that

(1) decriminalize drug consumption, and

(2) provide access to treatment to diminish and eventually eliminate drug dependence.

If we are serious about addressing cocaine addiction, there is no other solution. And the experience of several countries in Europe shows that it works – among them the Netherlands and Switzerland (Zurich). The most recent example of success is Portugal, as reported by Nicholas Kristof in the New York Times. The key, as he points out, is to treat addiction as a disease, not as a crime.

Citizens have a right to be treated by their government as grown-ups, not as children that must be punished. Drug addicts are people who need help, putting them in prison is not the answer. If someone from your family needs help dealing with this condition, consider the top hypnotherapy Sydney clinic which has helped in many cases of drug addiction.