A Trail of Blood (Part One)

This is the first of a two-part article investigating cocaine. Part One surveys the cost in human terms, focusing on Colombia, the world’s top coca producer, while Part Two investigates the environmental destruction caused by cocaine.

On August 10, President Trump told reporters he was getting ready to “declare the opioid epidemic a national emergency”, in response to a chilling report from the White House commission on the opioid crisis, that said “142 Americans die every day from a drug overdose”, a death toll “equal to September 11th every three weeks”. Trump promised “a lot” would be done to stop drug flows into the US and ensuring young people never use drugs but he didn’t mention access to treatment. And it is not clear exactly how he would proceed, particularly now that natural disasters wrought by hurricanes Harvey and Irma demand attention.

So far, Congress has done little except pass the 21st Century Cures Act that was signed into law by President Obama in 2016. It added US$ 1 billion over two years for drug treatment and disbursement has just started. Yet Trump talks up the role of the border wall and law enforcement while his proposed budget and congressional efforts to take down Obamacare are going in the wrong direction, preventing access to insurance to pay for treatment.

At state level, the move away from a criminal justice fix to the drug problem has been patchy at best. One reporter from Vox found that at least fifteen states followed Kentucky’s example of tightening penalties for low-level drug offenders, increasing mass incarceration rather than offering treatment.

Yet treatment is key.

The rest of the world, if not the US, has moved on past the obvious failure of the “War on Drugs” to focus on non-military, non-police, non-legal measures as possible solutions. That’s where improved access to treatment comes in. It is part of the UN Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goal 3, specifically target 3.5 which reads: “Strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol .”

Unfortunately, even within the United Nations, the political discourse is largely focused on other issues, like eradicating poverty as evidenced by the latest “outcome report” of the high-level “political forum” (10-19 July 2017), a ministerial meeting that reviews progress on the SDGs every year. Only one sentence addressed the drug problem: “We reiterate the need to strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse.” Surely stronger statements are required, more needs to be done.

Yet the US-waged “War on Drugs”, started some 60 years ago, and costing an estimated US$ one trillion should have taught us a lesson. It began when President Lyndon Johnson first proposed a toughening of penalties for drug trafficking in 1968; it ballooned with President Nixon in 1971, coming to Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. Whatever improvement America was able to achieve at home, it quickly vanished: Since 2009 there are more deaths from drug poisoning every year in the US than from firearms, motor vehicle crashes, suicide and murders, said a recent US DEA report.

Meanwhile, in the Andean countries, the war left a devastating legacy, clearly traceable to US aerial fumigation programs to stop coca cultivation and anti-narcotics policing that quickly spiraled into full-scale civil war, particularly ferocious in Colombia, pitting Marxist-inspired guerillas against the central government. The war in Colombia lasted until 2016 when the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARCs) agreed to a peace deal with the government, but not before there were some 200,000 dead and five million people forced out of their home.

The lesson from History is clear: fighting drug trafficking through military or police means solves nothing.

The US is the World’s Largest Cocaine User

The latest report (March 2017) from the Office of National Drug Control Policy on global cocaine trafficking confirms that the US is the largest cocaine user, consuming one third of world production.

Cocaine is known as a “rich man’s drug”, though one form, “crack cocaine” (smoked, not snorted) being much cheaper, is widely used in inner cities and by black communities, ensuring that the drug is prevalent in all social strata.

Cocaine is the second most popular illegal recreational drug in both Europe and the United States behind marijuana. More people use cocaine than heroin, and the number of cocaine users keeps rising (26 percent more in 2015 compared to the previous year, according to the U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health).

The street value of cocaine gives an idea of its importance as a recreational drug. One calculation, often cited, is based on a model developed in 2005 by the UN drug agency (UNODC) which estimated that the US cocaine market exceeds some US$70 billion in street value per year. This is likely to be a conservative estimate but still true today considering that cocaine prices have been (slightly) dropping over the past decade.

US$70 billion spent on cocaine is a lot, as much as Americans spend on playing the lottery, more than on books, video games, movies and sporting events combined (2015 data) – none of which have the devastating impact on health that cocaine has, particularly from chronic use.

Photo Credit: Häggström, Mikael (2014). “Medical gallery of Mikael Häggström 2014“. WikiJournal of Medicine

Coca Production on the Increase

Increased drug supplies mean more deaths: cocaine-related deaths in the United States have increased by about 60 percent since 2010, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

What makes the situation increasingly dangerous, is that production of cocaine in Colombia is higher than ever: according to the UN, it reached 866 metric tons in 2016, a 34 percent increase over 2015 when the war was still on-going. And that’s 200 million tons more than the average annual production of cocaine a decade ago (it stood around 650 million tons).

But some believe the UN data is too conservative. According to official American sources and InsightCrime.org that follows the situation very closely (with 110 visits on the ground over the last 2 years) production is likely to be closer to 1,200 tons. Hectares under cocaine cultivation, 145,000 ha in 2016, have gone back to the peak level of 2001. And the government’s coca leaf eradication program – adopted in 2015 when aerial spraying of herbicides was ended on health grounds – is giving mediocre results: only 18,000 hectares were pulled up in 2016.

Photo Credit: Insightcrime.org article (17 July 2017): “Record Cocaine Production in Colombia Fuels New Criminal Generation”

Clearly, the end of the war has not slowed cocaine production.

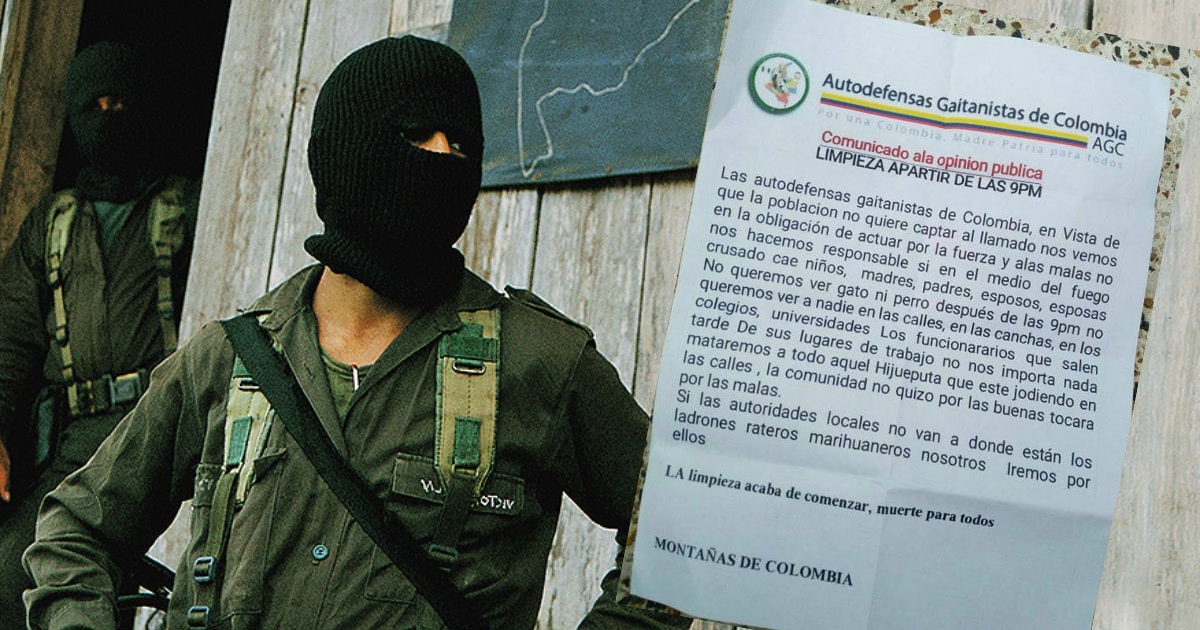

While the FARCs have (almost) disappeared, there is a “new criminal generation” of small guerrilla bands, the BACRIM (Bandas Criminales), according to a recent InsightCrime.org report. Most have moved away from now stale Marxist ideologies and they refrain from the anarchic cartel violence characteristic of Mexico. They boast an orderly and efficient Mafia-style network of paramilitary groups.

Among them, the most powerful is Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC). They don’t hesitate to take over local government, for example, as recently reported in Pitalito, that was already known as a money-laundering town in 2010, awash with drug traffickers.

In the Photo: The AGC pamphlet establishes a 9 pm curfew and threatens death to anyone walking the streets after that time, announcing: “La pimpieza acaba de comenzar, muerte para todos” (Cleanliness has just started, death to everyone). Photo Credit: Laboyanos Noticias, 23 April 2017

Has the War on Drugs diminished coca production in Colombia? No. Colombia used to produce 65% of the world total before the war escalated in the 1980s, now it is responsible for 90 percent. And this despite ten years of US aid costing $ 7.3 billion, known as Plan Colombia (2000-2010).

In fact, Plan Colombia didn’t work because it never addressed the root causes of the problem, abysmal poverty among peasants and a “failed state” unable to protect them. Originally meant to focus on economic development, Plan Colombia morphed into a standard military counterinsurgency project. While it weakened the FARCs, it failed to reduce the supply of cocaine to the US.

Plan Colombia only succeeded in displacing the war to Peru and Bolivia and bringing it North to Mexico in 2006 where drug cartels fight each other.

In the Photo: A coca plantation in Peru. Photo Credit: Benedicte Desrus

By 2013, it is estimated that some 27,000 Mexicans had gone missing and 120,000 killed. Today, most of the country (27 out of Mexico’s 32 states) is affected by a conflict killing more people than ever, with more homicides recorded in June 2017 than in any month over the last two decades.

All this while the flow of cocaine to the US is unabated, 90% coming from Mexico. With the demise of the Columbia drug cartels (Medellin, Cali and Norte del Valle) in the 1990s, the Mexicans have taken the lead, with a lucrative poly-drug portfolio of heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, marijuana, and to a lesser extent, fentanyl.

Trail of Blood: The Case of Colombia

The real cost of cocaine in the coca-producing and trafficking countries is usually ignored. Colombia, Peru, Bolivia and Mexico are far away, not the concern of American and European cocaine users. Yet cocaine raises serious moral issues that are best illustrated with what happened in Colombia.

Losses are stunning – as documented by Colombia’s National Centre for Historical Memory. They add up to a grand total of 7.6 million “registered victims” or 16.9% of the total population for the six decades the war lasted (1958-2013).

TABLE: Colombia Drug War Human Toll – 1958-2013

| Total Number of Victims | |

| Casualties (0f which fighters: 40,787) | 218,094 |

| Civilians killed | 177,307 |

| People abducted | 27,023 |

| Victims of enforced disappearances | 25,007 |

| Victims of anti-personnel mines | 10,189 |

| People displaced total

(low/high estimates: 4,744,046–5,712,506) |

5,350,000 |

| Children displaced | 2,300,000 |

| Children killed | 45,000 |

| Missing children (since 1985) | 8,000 |

Photo Credit: “Basta Ya! Memories of War and Dignity” report – figures for children also cited by UNICEF

Beyond the tragedy of death, the number of people displaced gives the true measure of the disaster: one in six Colombians was affected. But the children were the real victims. The FARC rebels, like all guerilla insurgency movements, had a devastating effect on the social fabric, drawing in children and women: Human Rights Watch in 2005 estimated that some 11,000 children had been enrolled in the ranks of rebel fighters, one of the “highest totals in the world”. And women were reported to comprise around 40 percent of the guerilla army.

Six Lost Decades

What is totally overlooked is the extent of the collateral damage in terms of decades of lost development.

True, Colombia started from a low point, its economy already weak in 1958 – and not because of cocaine. There had been a period of deep unrest known as “La Violenza” unleashed in 1948 with the assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitàn, a left-wing politician (Liberal Party) and an advocate of land reform who was running for the Presidency. News of the murder provoked a massive riot called the “Bogotazo” that killed upwards of 3,000 people and destroyed the center of Bogotà.

La Violenza, characterized by armed insurgents in rural areas, lasted ten years, killing at least 300,000 people – disclosure, I lived three years in Colombia (1958-1960), meeting people whose house had been burned in the “Bogotazo”, driving around the country with a gun in the car (for self-defense). What was particularly sad at the time, as everybody knew, the ultra-rich governing elite had enough funds to jumpstart the economy but, fearing the unrest at home, kept the money abroad in Switzerland and other safe havens.

The civil war traumatized every citizen, even if not a direct victim. In the 1970s and 80s, a wave of extortion and kidnapping engulfed the country, engineered by rebel groups to finance themselves before coca took over as the lucrative American drug market expanded. No one was safe at home. Wealthy Colombians left their suburban villas to live in the safety of high-rise apartments in town centers.

No government, no law, no human right could withstand the tsunami of violence and death.

Colombia, a country that, by all standards, should have been a star in Latin America after World War II, surpassing even Argentina, never made it. Yet, it had all the right playing cards in hand: a hardworking native population with roots in a strong millennial tradition; a long-standing culture, boasting the most refined form of Spanish in the New World with writers of the caliber of Gabriel Garcìa Màrquez, a Nobel laureate, and Candelario Obeso the precursor of African-American poetry; and an unmatched range of natural resources, including oil and emeralds, not to mention the best coffee in the world.

In the Photo: Colombia 1970 Map of economic activities. Photo Credit: Wikipedia

While Argentina didn’t make it either, mired in political squabbles dominated by Peron’s populism and militarism since the 1950s, Colombia suffered a much worse fate. And it’s not at all clear that it can recover even now, after the “reconciliation” with FARC rebels in 2016 that was stalled by a damaging referendum that rejected the peace deal. A subsequent agreement between the government and the FARCs allowed the peace process to continue and President Juan Manuel Santos was given the Nobel Peace Prize. One can only hope that award was not premature.

SEE RELATED ARTICLES: LESSONS FROM NOBEL PEACE SUMMIT AND COLOMBIAN PEACE PROCESS

IMPAKTER ESSAY: BREXIT, THE COLOMBIAN PEACE PLEBISCITE, AND TRUMP – A BEHAVIORAL APPROACH

The Cost of Political Corruption: The Cali Cartel Story

Corruption, historically a scourge of Colombian society, expanded exponentially with cocaine trafficking and the War on Drugs. The Cali cartel, run by the ruthless Rodriguez Orejuela brothers, is a perfect illustration of how corruption spread and damaged the whole of society, from top to bottom. It may look like a footnote in history, one among many drug cartels, yet at its height, in the early 1990s when it absorbed the rival Medellin cartel (after Pablo Escobar’s death in 1993), it was a $7 billion-a-year drug empire.

Viewers of the Narcos TV series who saw Jorge Salcedo, the new star character in Season 3 in action, gained a front-seat look into Colombian corruption. The head of security of the Cali cartel, Jorge Salcedo was the man who helped, at great personal risk, U.S. DEA agents to bring down the cartel. The series vividly depicted how corruption reached the highest levels of the state, including President Ernesto Samper who received more than US$ 6 million in cash donations from the cartel.

What is extraordinary about Jorge Salcedo, and what a TV film cannot show, is that he wasn’t a drug peddler or a bandit. He was born a member of the ruling class, the son of a Columbian general who himself had had a respected diplomatic career. He was a highly educated mechanical engineer who had honorably served as an officer in the Colombian army in the 1980s and started his career designing machinery and eventually running an oil recovery business.

Because Jorge Salcedo was proficient in electronic surveillance techniques, he was increasingly assigned to counter-terrorism operations, including some tainted by financial support from the Medellin cartel. That may be why, in 1989, at age 41, Salcedo was suddenly contacted by the Cali cartel and asked to organize the murder of Pablo Escobar. He said the call could not be refused.

Such details only came out many years later, when Colombian and US Justice had taken their course. President Samper and his Liberal party were badly damaged by the Proceso 8000 investigation (1994-95) into the Carli cartel’s political financing that found many of Samper’s associates guilty (Samper was absolved though he was Colombia’s last Liberal Party President). As to the Orejuela brothers, they were finally extradited to the US and sentenced in 2006 to 30 years in Federal prison. Salcedo, already in hiding with the Federal witness protection program eventually explained in a L.A. Times interview in 2007 how events had really unfolded (he had been in telephone contact with a reporter since 1998), noting “it was very risky, but I was trapped in a nightmare, in a totally corrupt environment. I had to escape.”

A senior drug cartel official who saw himself “trapped” in corruption? If that sounds exaggerated, it isn’t. Salcedo’s story is emblematic of how corruption affected everyone, even people like him, belonging to the elite, basically honest, hard-working and family-loving, the kind of citizen that in a normal environment should have thrived and helped the country develop. Salcedo, of course, did not thrive, and neither did Colombia.

A Stalled Agrarian Economy

Drug traffickers distorted the distribution and use of land. Not only did coca cultivation have a devastating impact on the environment (to be explored in Part 2 of this article), but, as the Colombia office of the Comptroller General noted, drug traffickers bought large expanses of land in rural areas, thus increasing income inequality and contributing to the displacement of peasants.

According to those estimates, about one million hectares were in the hands of drug lords in 2010, although some claimed the figure could be as high as 5 million hectares. Because it skewed land ownership and introduced a yet higher rate of income inequality than the one that existed before, this phenomenon was called the “agrarian counter-reform.” Certainly not an improvement for farmers already suffering under the yoke of the land-owning oligarchy since Spanish colonial times.

A Militarized Economy

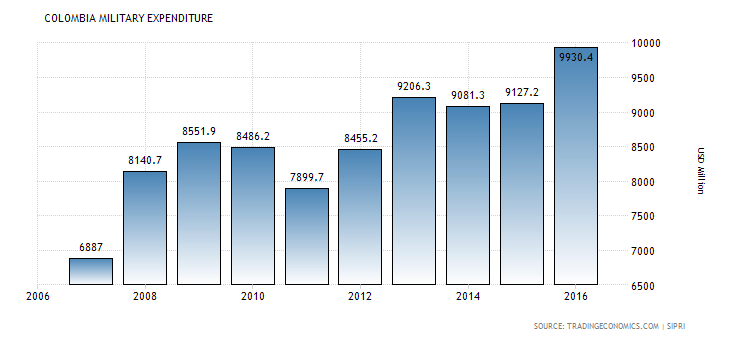

Colombia is the most militarized country in South America, regularly spending twice as much as any other country in the region.

Photo Credit: Trading Economics

2017 is not looking any better. Because of the uncertain situation with the FARCs and other paramilitary groups continue to thrive, an increase is planned in the 2017 budget for military expenditures (plus 2 percent, US$ 120 million). Meanwhile expenditures on social programs are reduced so that an “austerity” budget can be presented: the goal is to maintain the approval of international investors (maintaining a BBB rating).

With the country needing to recover from 60 years of war, a reduction in social programs seems particularly ill-advised.

A Lost Generation

The fact that 2.3 million children were victims, a third of the total, bodes ill for the future. As reported by a recent UNICEF/Colombian study of 1,666 children, war impacted them deeply, affecting their mental health. The road back to normalcy will be hard: while individual trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy works well in high-income countries, the situation in war zones is different because of a lack of funding and professional therapists. And it is not likely to be any better in a more peaceful Colombia, since the 2017 “austerity budget” proposed by the government will further slash already insufficient social programs.

In the Photo: The slum El Calvario in Cali, Colombia, where the informal economy has become the only source of survival for its inhabitants. Photo Credit: Jan Sochor Photography

The outlook is grim for Colombia and one can only hope that the country will find the energy to recover, it deserves so much better. As Gustavo Silva Cano, a young Colombian studying law in the United State wistfully wrote in 2010, decrying the death and drug violence in his country:

“Imagine a peaceful Colombia, free of cocaine, free of Pablo Escobars, Carlos Castaños and Manuel Marulandas… Imagine, for example, that due to some mystery of fate, Colombia’s soil had proven totally incapable of growing marijuana and coca plants. Or, even better, imagine that the easy-money culture that comes with drug trafficking had never taken hold of the Colombian people. Just for one second, imagine…”

Yes, just imagine. He added the “beauty of that thought is so painful that it makes me want to stop fantasizing,” but neither he, nor we should give in. If only people in America and Europe would stop using cocaine, if only the War on Drugs had been waged against demand and not supplies. If only…

Yet it is possible to imagine a better future, that is the way forward: A war on demand. And offering treatment instead of dropping bombs.