Have human beings already doomed our species? How far does global warming have to rise for us to go extinct? Is there anything we can learn from how Homo Sapiens endured previous extremes? Do we have the political will to halt climate change?

It was a splendid June at my cabin by the river. As we sat on the porch, lazily watching sunlight dazzle the eddies, a kingfisher dove and splashed while ravens wheeled over the pines in their enormous dignity. Every breath we drew was redolent with honeysuckle.

“I am so worried,” I said to my friend, “that all of this natural abundance will be destroyed by global warming.”

“None of these lovely things need human beings to endure,” he replied. “Nature can survive as abundant and changeable as ever. It could be very different for us, though: there might be lots of new species, but ours might not be one of them.”

Or, as Brandon Keim puts it, even if we are still here, “Climate change will shuffle nature’s deck; And we might need to embrace it.”

Nonetheless, my anxiety that we careless humans might have already doomed our beloved planet was lightened by the possibility that, in all of its abundance and complexity, nature itself might actually survive.

COMING DOWN OUT OF THE TREES

I have always been told that one of the reasons we evolved from apes is that we abandoned trees to walk upright on the ground.

Human beings branched from primates 7 million years ago, at a time we were both challenged by hot, dry plains replacing forested landscapes. Those primates “Offer a Glimpse of Our Evolution,” writes Carl Zimmer in the New York Times. Enduring temperatures of 114 degrees, chimpanzees in the present day Fongoli area of Africa have adapted to blistering daytime temperatures by sleeping in the daytime and foraging at night.

Faced with similar conditions during our evolution, Homo Sapiens developed an upright posture that enhanced the flow of air across our upper bodies; while our development of sweat glands gave us further advantage in searing heat.

LUCY AND A SPIKE IN CARBON

Changes in climate enhance evolutionary developments by requiring adaptations to new circumstances.

The skeleton of Australopithicus “Lucy”, for example, displays her capability both for for walking and for climbing trees; her species survived for 900,000 years in a variety of climate conditions.

Lucy evolved during a cool period disrupted by intense monsoons, but was still around when it was four degrees warmer than now with a 360-400 parts per million (ppm), a level of carbon dioxide similar to ours.

THE HUNTER-GATHERERS

In My European Family: The First 54,000 Years, Karin Bojs tells how Neanderthals were able to survive the intense cold of the Ice Age (24,000-18,000 years ago) only to be bested by the inventive brains of homo sapiens whose superior cognition and more efficient language development led to better survival techniques like long-term planning and clever battle strategies. We also invented more efficient hunting implements than theirs and bone needles to sew furs tightly for better winter survival.

According to Bojs, after the ice age Cro-Magnon and other hunter-gatherers migrated north along with the animals they depended upon for sustenance; when necessary, they took to fishing and hunting seals.

About 8500 years ago there was a 300 year period of re-Glaciation which Homo Sapiens survived, only to endure a period of global warming.

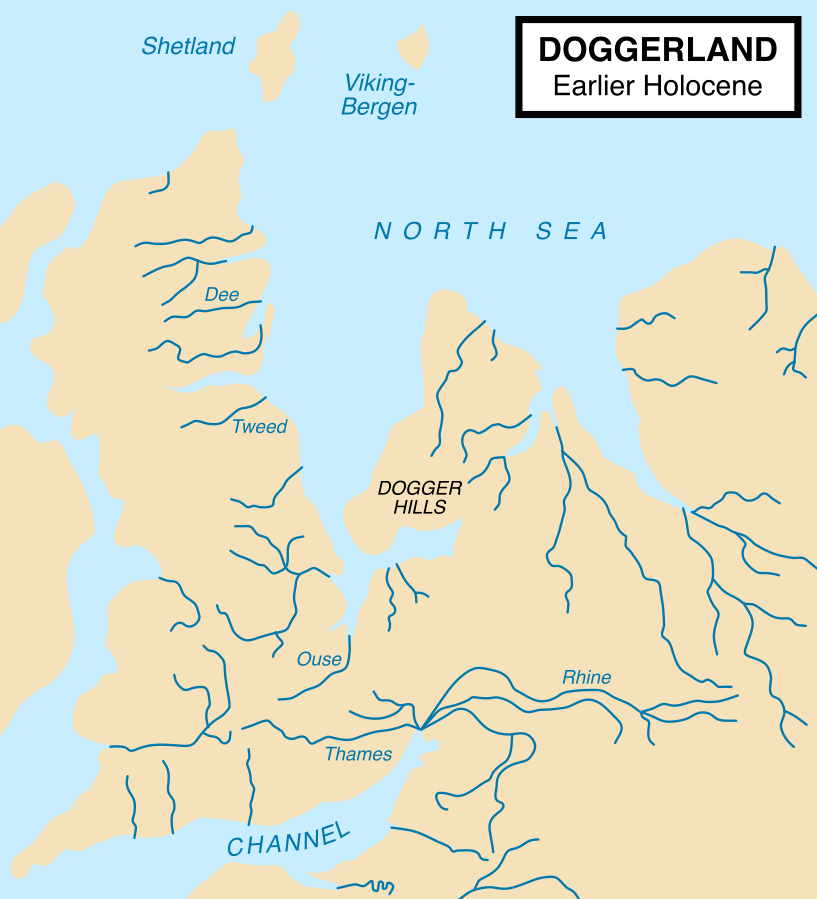

“So you think climate change is new?” asks Koert van Mensvoort, “you must have not heard of the times when people walked from London to Amsterdam…. Doggerland is the name of a vast plain that joined Britain to Europe for nearly 12,000 years, until the sea levels began rising dramatically after the last Ice Age. Taking its name from a prominent shipping hazard – Dogger Bank – this immense land bridge vanished beneath the North Sea around 6000 B.C.”

Source: Doggerland linking England to the continent, Mapping a Lost World by Max Naylor ( GFDL from Wikimedia Commons, 2009)

AGRICULTURE AND OWNERSHIP OF PROPERTY

Although tribes might chase rivals away from the territory they utilized, hunting and gathering required landscapes which don’t belong to anyone in particular; the idea of land as fixed parcels of property under individual or family ownership came with the arrival of agriculture.

Bojs describes two large scale migrations of Homo Sapiens into Europe: waves of agriculturalists arriving from the Middle East with all of their farm equipment, animals and seeds on boats about 9000 years ago, and the incursion of nomadic Aryans from the eastern steppes 4500 years ago.

In much of Europe, the first migration led to the replacement of hunter-gatherers with large fixed settlements and a hierarchical governance based on land ownership and sufficient military force both to protect it and to subdue others to work it for you. The second migration of Aryan nomads eventually adopted the agricultural way of life of the peoples they conquered.

GENETIC ADVANTAGE, GENETIC PERIL

Although before the industrial revolution human beings survived climate warming, glaciation, and every kind of natural catastrophe, our low populations and agrarian lifestyle kept us from causing wide-spread climate change.

Tragically, it is precisely Homo Sapiens’ most significant genetic endowments – our inventiveness and our mutual cooperation (the latter including organizing for inter-tribal warfare) — which lead to anthropocentric climate damage.

In the Medieval feudal system in Europe whole villages subjugated themselves to a hereditary caste of leaders in exchange for protection during times of war. As nations were formed and property ownership spread, governance spread beyond hereditary hierarchies to a wider populace, ruling itself with contracts and covenants like the Magna Carta in England, The Mayflower Compact in Massachusetts, and the United State’s Constitution.

Unfortunately, this covenantal cooperation did not preclude a sense of tribal supremacy such as led in America to the enslavement of African Americans and extirpation of the native hunter- gatherer populations. The tragic irony of “the enlightenment” and “the industrial revolution” is that our technology outstripped our commonality.

Militarily, our weaponry has long undermined our common sense. In the First World War, for example, the ridiculous strategy of charging into lines of fire in cavalry formation destroyed an entire British generation.

The Second World War ended with our application of the laws of atomic physics to weapons that threaten the “mutual assured destruction” for a huge swath of the earth’s population. We thought that the “modern” 20th century would bring us to a technological utopia; now we look back on it as “The century of total war.”

Homo Sapiens, fortunately, is a work in progress; our superior brains and strategic planning help us evolve toward cooperation when ferocity becomes dysfunctional.

Six warring eastern tribes, for example, renounced their long-time and especially vicious inter-tribal warfare to form the Iroquois Confederacy in the 16th century. According to a group of American Indians and scholars, this Federacy operated under an unwritten democratic constitution that served as a model for the American colonists who were impressed by its governing principles of peace, justice and “the power of the good minds,” that of the elders. For example, at the Albany Congress in 1754, Benjamin Franklin championed the Iroquois example as he presented his Plan of Union.

The result, the United States Constitution, was based on a separation of powers or system of “checks and balances” allowing the President, the Congress, and the Supreme Court to keep each other from becoming too powerful. This served very well until the present when t

he United States Constitution, as well as a series of international covenants like NATO and the Paris Climate Agreements are threatened by a fresh upsurge in tribalism (Make America Great Again!) and nationalism (America First!).

POSSIBILITIES FOR EXTINCTION

“Climate-change skeptics point out that the planet has warmed and cooled many times before,” writes David Wallace-Wells in an article ominously entitled “The Uninhabitable Earth”. And he points out, “the climate window that has allowed for human life is very narrow, even by the standards of planetary history. At 11 or 12 degrees of warming, more than half the world’s population, as distributed today, would die of direct heat.”

Since we are at two degrees now with four degrees a distinct possibility in this century, we are on a trajectory to species extinction.

Human survival depends on adaptations we have already made and techniques we have developed to draw down carbon emissions. Presently, our cognitive ability and our political will is undermined by three specific flaws that threaten efficient governance of the res publica:

(1) an overvaluation of individual autonomy;

(2) an elevation of profit-based mercantilism over the common good, a.k.a greed;

(3) a resurgence of racial and national tribalism, a.k.a. populism.

Individual autonomy

Robert Reich finds our common good undermined by excess individualism. In his new book The Common Good, he defines this as “our shared values about what we owe one another as citizens who are bound together in the same society.”

He identifies our particular strain of anti-social individualism as the one fostered by the late writer Ayn Rand, who Donald Trump declares his favorite writer and whose books the Leader of the House of Representatives Paul Ryan requires his staff to read.

Influential among a wide swathe of conservatives and libertarians, Rand values individual autonomy as the most important human value and considers the common good its implicit enemy.

Greed

Marilyn Robinson in an essay drawn from her new book What are We doing Here? describes “Neo-Benthemism” as an economic system that fosters “our unquestioning subservience to the notion of competition”. Based on greed for the accumulation of wealth, it uses an ethical code based on a mercantilism grounded in “cost-benefit analysis.”

Market fundamentalists, holding that if businesses are only left on their own the national economy will prosper, have deregulated the protection of such common goods as the water we drink and the air we breathe.

One horrific example of how mercantile ethics are destructive to human life will be sufficient. Starting in 1977, the Nestlé Company faced an unprecedented boycott as a result of its aggressive marketing of breast milk substitutes (especially in developing countries where clean water is often unavailable).

Over the next few decades, the superiority of breast milk as the best source of nourishment for infants was amply confirmed by science and found support from the World Health Organization. Yet as recently as July 2018, the Trump administration’s delegates to WHO tried to reverse international consensus on the goodness of breast milk, They succeeded in watering down a resolution to promote breastfeeding, making it less easy to implement in developing countries. While all the delegates did sign on, including the Americans, the Trump Administration got some of what it wanted: WHO was enjoined not to assist developing countries in implementing breastfeeding.

Controlling all three branches of government, the Republican party has declared war on the common good by scuttling covenantal arrangements like nuclear treaties, trade alliances, human rights agreements and climate accords, all in the name of individual autonomy, what is good for business, and what will foster white supremacy.

Populism

Severe economic inequality has left a significant portion of the American population suffering the terrors of unemployment and the indignity of status loss. When the common good is taken as the good only of the wealthy, trust in any kind of governmental covenant is eroded.

White people have been not only the majority but, more crucially, the norm in the United States since its inception and they are infuriated to see themselves becoming a minority in the population.

As Reich explains in his book:

“Where a sense of common good is lacking, demagogues can use the anger and fear accompanying disruptive change to turn people against one another rather than address the traumas that made them angry in the first place. Societies experiencing economic stresses and widening inequalities are particularly vulnerable to tyrants intent on undermining democratic institutions by lying repeatedly, accusing critics of conspiring against ‘the people,’ fueling racial and ethnic divisions, and inciting rabid nationalism.” (p.28)

POSSIBILITIES FOR SURVIVAL

Going Local

In a New York Times opinion piece entitled “Where American Politics Can Still Work: From the Bottom Up,” Thomas L. Friedman describes how the town of Lancaster that seemed to be dying less than 20 years ago has become a Pennsylvania success story, bringing itself back from economic decline; he attributes the city’s success to “a complex adaptive coalition.”

Focusing on issues rather than on Party (political tribalism) and not waiting for their State or their National Government to solve its problems, Lancaster has been able to develop flexible covenants to renew downtown and make the city economically viable.

In terms of banding together to fight global warming, such “complexes of adaptive coalitions” are being created all over the United States, where cities, states, tribes, businesses, universities, claim that they are already half-way to meeting the Paris climate standards.

Going National

Members of Congress display considerable political will to fight climate warming. The Climate Solutions Caucus in the U.S. House of Representatives, for example, is a bipartisan organization (84 members, half Democrats and half Republicans) dedicated to climate legislation.

At the time of writing, 16 states and Puerto Rico have joined in the U.S. Climate Alliance, a coalition of state governors, and are working to “reduce gas emission by at least 26-28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025.”

Going International

Even with the withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Climate Accord, the rest of the world has dedicated itself to draw down carbon emissions. Will this be enough to avoid human extinction?

Jeremy Hance in an article about scientists calling for a Paris-style agreement to save life on earth, does not mince his words and calls for more action from the private sector:

“Let’s be honest, the global community’s response to the rising evidence of mass extinction and ecological degradation has been largely to throw crumbs at it. Where we have acted it’s been in a mostly haphazard and modest way — a protected area here, a conservation program there, a few new laws, and a pinch of funding. The problem is such actions — while laudable and important — in no way match the scope and size of the problem where all markers indicate that life on Earth continues to slide into the dustbin. But a few scientists are beginning to call for more ambition — much more — and they want to see it enshrined in a new global agreement similar to the Paris Climate Accord. They also say that the bill shouldn’t just fall on nations, but the private sector too.”

This “radical conservation” calls for setting aside one half of the earth’s surface, to consist of areas already protected from industrial development plus further set-asides in every nation, where carbon will be drawn down rather than emitted on a significantly widespread basis.

CLIMATE CHANGE: HOW TO WALK THROUGH OUR FEARS

Our worst case scenario is that even if nature itself survives global warming, we human beings will first endure ever more intolerable heat, storms and fires and then become extinct altogether.

I didn’t want to go see Al Gore’s movie, “An Inconvenient Truth,” when it came out because I knew that witnessing his evidence of global warming would terrify me right down to my toes. But then, eleven years ago now, I attended a speech he gave on the fear of global warming at an Omega Institute conference in New York City.

“Hi, I’m Al Gore, I used to be your next president of the United States,” he introduced himself, to laughter all around, and then went on: “FDR said that ‘the only thing we have to fear is fear itself’ but I don’t agree with a word of it. Fear is important, you need to embrace fear.”

We should not let the impacts of global warming overwhelm our ability to reason, he went on. We need to live with our fear, walk through it, to confront global warming is a symptom reflecting a conflict between our civilization and our ecosystem.

Following the ecological thinking of Teilhard de Chardin, Gore understands the universe is a complex but single organism in the process of unfolding, with the human mind or consciousness as one among other elements in its evolution. Nature, Homo Sapiens, and the universe are moving toward an “Omega point” where individual consciousness, community, national consciousness and the consciousness of the universe meet.

We must walk through the danger revealed to us by our reason, said Gore; we must acknowledge our fear and dread and then turn these emotions into a source of energy and opportunity, working together to accomplish the common good.

“May the things of this world be preserved to us, their beautiful secret vocabularies.” Parker Palmer

Editors Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com

Featured Photo Credit: Beavertail Cactus in the Wonderland of Rocks, Joshua Tree National Park (Southern California) photo: NPS/Hannah Schwalbe (Flickr) Photo of Lucy:By Nachosan (Wikimedia Commons)