“Actions speak louder than words” says Chinese President Xi Jinping in defence of Joe Biden’s criticism towards the Head of State for not showing up to COP26 in Glasgow. “What we need in order to deal with climate change is concrete action rather than empty words” he adds, “China’s actions in response to climate change are real.” The concrete actions he was evoking could very well come – at least in part – from an unexpected direction: sustainable proteins. It would appear that in the fight against climate change, the food sector matters.

For now, we are yet to see China’s leadership in the fight for climate change, as COP26 revealed nothing more than an absence towards greater and more impressive ambitions. Currently, China’s goals are to peak in carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and become carbon neutral before 2060.

When tackling climate change, the focus tends to be on ‘clean energy’ solutions, and rightly so, as energy whether in the form of electricity, heat, transport, or industrial processes account for the majority (74%) of greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, the global food system is also a key contributor to emissions (26%) for which we lack viable technological, economical, and societal solutions.

The agricultural sector, in particular, has a massive carbon footprint. Livestock farming, including feed production and processing, accounts for around 15% of annual greenhouse gas emissions, including 32% of methane emissions. Animal agriculture also accounts for one third of water use, and over 70% of antibiotics. In addition to its effect on climate, the expansion of agriculture has caused massive losses in biodiversity around the world.

Today, China consumes 28% of the world’s meat, and half of it is pork. The biodiversity of the country with the continuing expansion of agriculture is, also, very much under enormous threat. The combined effects of habitat destruction, fragmentation, environmental contamination, over-exploitation of natural resources, and introduction of exotic species has led to immense biodiversity loss.

In order to realistically meet its climate change goals a sustainable transition within their food production is essential. Similarly, if China is serious about becoming a global leader in conservation, presented as more than simply hosting the UN Convention on Biodiversity (COP15), then transitioning towards plant-based, fermented, and cultured protein, could support both these goals.

Protein Producer Index

The Protein Producer Index, measured by Coller FAIRR, is the world’s only assessment of the largest meat, dairy, and farmed fish producers tracking their economic, social, and governance (ESG) impact. They studied the world’s 60 largest publicly listed protein producers and found that 40% of the total market capitalisation were Chinese companies.

The Index encompasses the ten risks listed below and rates business taking them into account:

Out of the 12 Chinese companies, all of them rank as “high risk” when it comes to deforestation and biodiversity impacts, whilst ten of them are “high risk” overall in all ten categories.

China’s move towards net zero must, therefore, focus as a matter of priority on biodiversity and deforestation, and thus it must incorporate measures pushing for sustainable proteins and food.

China and its history with soybeans

Investors and entrepreneurs are seeing new financial and strategic opportunities in turning and investing towards alternative proteins. Not only does China have good potential for developing a market for meat-replacements, it is also a major supplier of plant-based protein, most notably soybean – it is the fourth largest producer globally behind Brazil, the US, and Argentina.

Prior to becoming the greatest global pork eater in the middle of the twentieth century, the majority of Chinese citizens were more vegetarian than not. This had to do with the country’s long history with soybeans.

Most of its domestic soybean production was and still is located in Heilongjiang, which prides itself on its black soil and non-genetically modified seeds to produce safe, healthy, and sustainable soybeans. The seed was considered to create a flex crop which could be used for a variety of products and adapt over time as demands changed. In the 1900s, the Chinese invented several methods for transforming soybeans into different varieties of tofu which suited current consumption preferences.

Related Articles: How to Make Agriculture Carbon-neutral: Lessons from Denmark | Voluntary Sustainability Standards: From Bananas to Palm Oil | Wilder & Harrier: Innovative and Sustainable Pet Food

China’s population exponentially grew since the 1900s and reached its highest yearly population growth rate in the 1970s. Feeding its citizens became a top priority for the central government.

But it faced two issues: (1) it did not have enough arable land to feed off everyone with soybeans, and (2) the lack of soybean also meant it had limited resources to produce animal feed. As a result, in the 1970s the government designated the feed sector as a priority industry, aiming at increasing the national capacity of producing animal-based products.

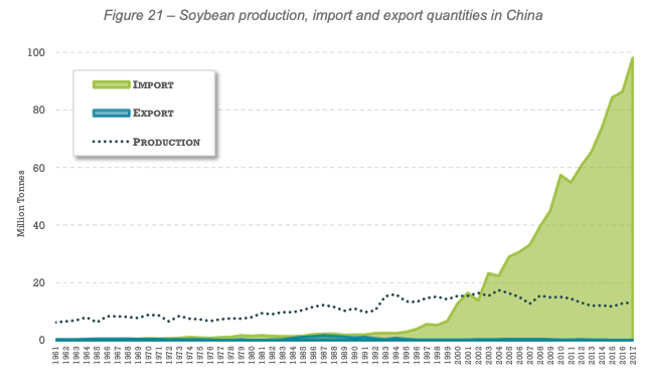

In the 1990s, China became the largest consumer and producer of feed ingredients and livestock products, and soybean imports from China grew from 2.9 million tonnes in 1995 to over 98 million tonnes in 2017 from the US, Brazil, and Argentina.

The revived soybean markets

Rising rates of obesity and chronic diseases linked to unhealthy lifestyles and diets, coupled with repeated outbreaks of avian and swine flu in recent years, have sparked greater demand for alternative proteins among the Chinese health conscious.

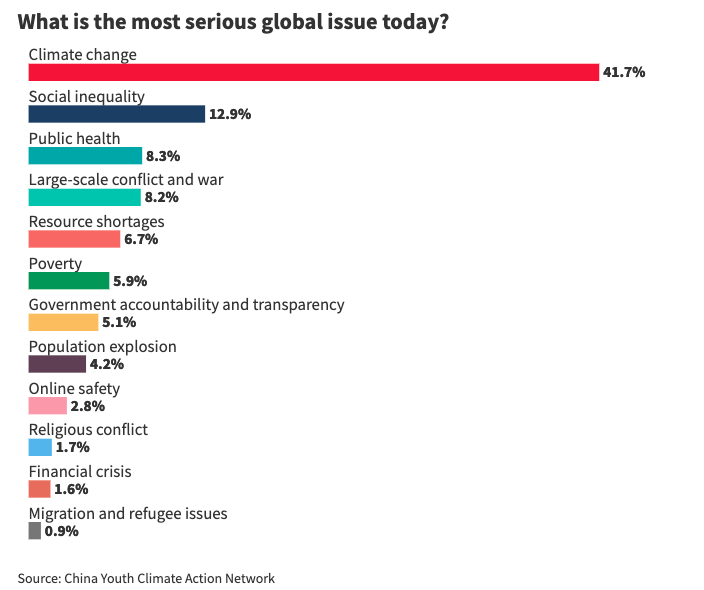

China’s youth, more attuned with the environmental impact of meat-eating, deforestation, and due to their greater care for animals, have changed consumption patterns – gearing towards vegetarianism or veganism.

With these new demands, soybean became more expensive to produce as it needed to ensure it was deforestation-free in an already highly price-sensitive industry. With the tighter profit-margins, farmers sought to diversify their product portfolio, engaging in greater innovation in how to replace meat products, rather than using plants to feed their livestock.

The central government is supporting the rise of its alternative protein market. In 2021, a Chinese-government affiliated Chinese Institute for Food Science and Technology, established the first voluntary standard for the industry. This contained definitions, technical specification, and guidelines to govern the labelling, packaging, transportation, and storage of plant-based meat alternative products in China.

So far, China’s alternative protein market has been driven by foreign players such as Beyond Meat, Impossible Food, or Oatley, supplying fast food chains such as KFC or McDonald’s. With the help of the Chinese government, businesses located in China will be able to compete with US giants and include plant-based alternative products into staple Asian Cuisines.

In 2017, the Chinese government had already backed cell-based meat in a recent deal with Israel. Faux meat is nothing new and can only grow exponentially. CellX and Zhouzi Weili – two pioneers in the Chinese market – are currently working on creating cultured meat. It is estimated that the global industry will grow fivefold between 2020 and 2035, to $162 billion.

The global shift to plant-based diets could lead to a 70% decrease in greenhouse gas emissions caused by food production by 2050.

It is crucial that China plays its part in this global shift and doing so could be a win-win: Not only would it provide China with a solution in meeting its climate change goals, but also it would help meet its public health policies.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Loaded Sweet Potato Fries Bowl. Featured Photo Credit: Ella Olsson.