A Win for China, A Loss for America and a Transformed G7 Balance of Power

Updated 25 March 2019. On 22 March, at the close of President Xi Jinping’s visit, Italy signed a comprehensive economic agreement as part of the “New Silk Road” with China. A so-called Memorandum of Understanding, it is a framework agreement containing a total of 29 separate agreements. Ten are “commercial”, ranging from the Italian energy giant Eni to Ansaldo, a major producer of thermoelectric power plants. And nineteen are “institutional”, covering a broad range of activities, from cultural exchanges to defense of archeology sites and collaboration in public health matters and in UN agencies like UNESCO. The sum total of agreements is reported to have a potential value of around €20 billion.

The news is sending shock waves across Europe and America.

The U.S. is pressuring Europe not to use the Huawei technology claiming it’s spyware and France where Xi Jinping is visiting after Italy is trying to re-establish a united EU front. President Macron invited German Chancellor Merkel and EU Commission President Juncker in Paris for a meeting on 26 March to discuss the “New Silk Road”.

Yet France is also signing this week a series of agreements with China, similar to what Italy just signed. And Monaco that Xi Jinping visited on 24 March has decided to sideline U.S. demands and let Huawei help it launch the new G5 technology.

The big difference between France and Italy’s approach to China is that France, unlike Italy, has decided to not do it alone. And it wants to stand up to China, make it a “reciprocal New Silk Road”. So that leaves Italy playing alone – with the risk of giving too much rope to China. But it can certainly claim to have been the first of the G7 members to join China’s “New Silk Road”. A dubious claim at best.

The upshot however is that everyone in Europe, sooner or later, is joining China’s Silk Road, regardless of whether it is really “new” or “reciprocal”. The G7 is really becoming a G6+1, where the +1 is the United States.

Why did Italy do it? To say that it was in deference to the historic Silk Road that linked Ancient Rome to China sounds good but it’s not the whole story, by far. First, a word about the Silk Road, also known as One Belt, One Road (OBOR) and The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

BRI amounts to the biggest investment abroad by any country since the Marshall Plan, and it is China’s calling card to the world. A major geopolitical strategic move that is central to China’s foreign policy and looking increasingly imperialistic. Except it’s tailored-made for the 21st century as war among nuclear powers makes no sense. This is not a military war but an economic one. And may the strongest win.

But has Italy really fallen in China’s lap, lured by the riches of its Silk Road? Washington ad Brussels fear that is the case.

Predictably, Washington reacted negatively right away, as soon as Prime Minister Giuseppe Conti announced on March 8 that Italy would sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s trip to Rome. The U.S. National Security Council took to Twitter warning that Italy’s participation in BRI would “bring no benefits to the Italian people.” But it is unlikely the U.S. will make a move (for example, like discouraging investors from buying Italian debt). So far U.S. allies such as Poland, New Zealand and Israel have also signed MOUs on BRI with little consequence.

Italy’s European allies are similarly conflicted. No liberal democracy can accept China’s values or disregard for human rights, but France and the European Commission, in various joint declarations have often been open to cooperation with China on BRI projects.

But Italy’s biggest mistake was the fact that it did it alone, without any consultation with fellow EU members. Germany and France are understandably angry. Italy, with its Euro-skeptic nationalist government (Vice Premier Di Maio, of the % Star Movement, is a leftist populist, Vice Premier Salvini, leader of the Lega, is an extreme right populist) has already isolated itself from Brussels and gotten into several diplomatic squabbles with Paris. This new agreement with China will only make matters worse for Italy and ensure that (for a while at least) Italy will be considered a political pariah with no say in the European concert of nations.

So why did Italy do it?

The Lure of the Silk Road

Italy is debt-ridden and cash-starved, so why not look for Chinese help?

Also Italy is far from being alone in Europe in doing so. Italy’s ANSA news agency reported that Luxembourg is also currently in advanced negotiations with China to sign a similar agreement. And this agreement would make Italy not the first, but the 17th European country to join BRI.

The other 16 European countries that have joined BRI are Central and Eastern European (11), including the Western Balkans (5), and since 2012, they have formed a group known as 16+1, the one being China. Needless to say, this group is led on the European side by authoritarian populist leaders like Hungary’s Viktor Orban and Poland’s Jaroslaw Kaczynski.

So the Silk Road is growing, and with Italy joining it, it would be at last historically complete – if one is to follow Xi-Jinping’s poetic views of his BRI. Yesterday, in advance of his visit, Xi-Jinping wrote a remarkable article that was published on the Corriere della Sera, waxing lyrical and insisting that this is “a strategic pact with Italy”, with deep roots in History, going back 2000 years, to the times of Ancient Rome.

Americans, with Trump currently engaged in a trade war with China and trying to convince European allies (without success) that the digital giant Huawei 5G equipment is a dangerous conduit for spying, have of course a tendency not to share Xi-Jinping’s rosy vision. Even liberal media like Vox. Take a look at their excellent video that explains what the Silk Road, China’s “trillion dollar plan” to dominate the world, really is. It is guaranteed to send chills down your spine:

Rumors are swirling in Italy as people wonder exactly what this “memorandum of understanding” entails. The Italian government insists it is just a framework agreement, implying there isn’t much to it. MOUs are generally non-binding. Like a skeleton without flesh.

But the flesh seems to be coming. Bloomberg recently reported that a number of major Italian business firms were involved in framing this agreement, from banking and energy to soccer clubs. Soccer clubs may not be strategic areas, but energy and banking certainly are. And Bloomberg dropped big names: gas pipeline operator Snam SpA, engineering company Ansaldo Energia SpA and leading banks like Intesa San Paolo and Unicredit.

And it’s not going to be just one overall memorandum of understanding between China and Italy. It’s going to be several, covering different sectors. Fully 30 agreements are coming, for a total of at least €7 billion new business. For example, it is reported that Snam will sign a memorandum of understanding with China’s Silk Road Fund for cooperation on international investments, potentially also involving and Italian state lender Cassa Depositi e Prestiti SpA.

In a way, this sort of agreement is organic: It is merely the continuation of activities SNAM had already started in China in 2018 when it entered the Chinese market with three agreements: with State Grid International Development, Beijing Gas, and PetroChina Pipeline Company.

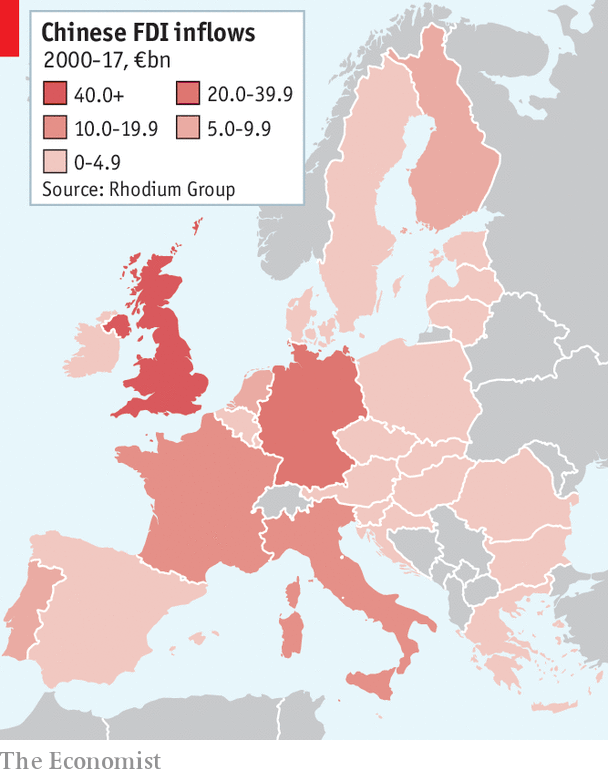

Chinese investment in Europe is nothing new and has been going on steadily since the early 2000, as this graphic shows, with the UK taking the largest share followed by Germany, with Italy and France coming close behind:

Arguably, the tenor of China’s growing presence is changing and seems more threatening with the advent of Xi-Jinping, who last year engineered a constitutional change that made him into a president for life.

Australia’s ABC News recently painted a striking portrait of the Chinese leader:

It is clear that Xi-Jinping is a strong authoritarian leader and with him, what China wants, China gets.

Yet BRI is arguably not in the best of health. Many countries are finding that the benefits are not as promised. The African and Asian countries that have joined BRI have a growing debt that they do not control; they sign infrastructure projects that are not always transparent and even turn out to be sometimes useless for them, often crumbling before they are completed.

What Next?

The Italian government itself appeared divided, with extreme right populist Lega leader Vice Premier Matteo Salvini on one side warning against foreign interference and calling for strengthening the so-called “golden share” that gives the Italian government control over the management of private companies it invests in.

On the other side, you have extreme left populist 5 Star Movement’s Vice Premier Luigi Di Maio who was looking to boost the Italian economy, particularly as he is going ahead with his “citizens’ income”, a version of UBI (Universal Basic Income) that threatens to bankrupt the Italian Treasury at a time when Italy has gone into recession.

The agreement was signed over Salvini’s objections, and it is likely to lead to renewed Chinese investments and increased trade between the two countries.

It is also clearly in China’s interest to enroll Italy in BRI. Consider the slowdown in Chinese FDI last year: It dropped to $30 billion in 2018 from $111 billion in 2017, according to the latest analysis from Baker McKenzie in partnership with leading research provider Rhodium Group. Chinese investment (FDI) in Europe and America thus fell 73% to a six-year low. Slowdown is due to new investment screening regulations, trade tensions and Chinese investment controls.

Finally, there are the financial instruments to flesh out the skeleton of MOUs.

On the Chinese side, you have the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank that was launched in January 2016 and has now grown to 93 approved members worldwide, including major European countries, like the U.K, Germany, Italy – but not the U.S. The Bank serves as a major conduit for BRI projects – and hence, for funding Italian infrastructure, ports and highways.

On the Italian side, Italians are jumping into bonds, the “panda-bonds” to raise funds in China with support from the Italian state lender Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (the bonds will be denominated in Renmimbi). The panda bonds will become operational as soon as the Chinese authorities give their green light.

The stage was financially and economically set. The political show has started.

And what is most notable in this show is the American absence. And Europe’s disapproval at the fact that Italy went ahead on its own.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.

In the cover photo: Chinese President Xi Jinping with Italian Prime Minister Conte Source: Reuters