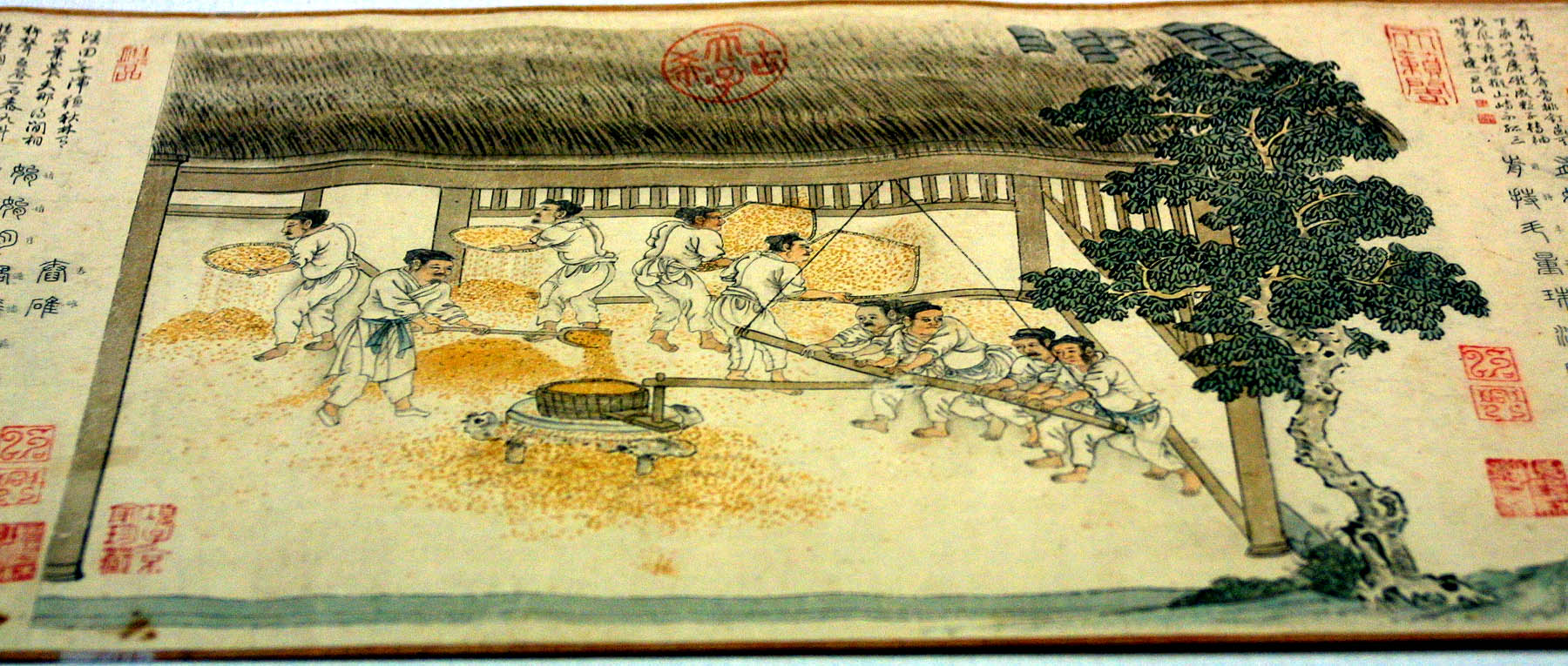

China’s development model is raised as an alternative to the Western free market-based approach. China’s rapid growth in the past three decades has widely upended the idea that the western neo-liberal ideology would spread internationally unimpeded. The pace of economic change in China has been extraordinarily rapid since the start of the economic reforms over 25 years ago. Its economy has undergone a massive transformation and is now the largest in the Asia-Pacific region. It has shifted from a predominantly agricultural one to becoming an industrial powerhouse and is now far more service-oriented.

The Chinese development model is based on continuous and selective state interventions in markets and firms with the objective of shaping the course of economic development.

During the early 1970s, China was economically isolated and in a situation where it faced several threats from the then two superpowers: the Soviet Union and the United States. Today, the debate revolves around how far Chinese ideas could spread, as most of the world sees China as reaching out for global power and influence.

China’s reforms have undoubtedly resulted in fast and continuous growth in the past three decades and have also lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty. For years, the United States has used its hegemonic power and influence in the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) to guide developing countries towards capitalism and liberal democracy.

This scenario is changing now.

As a result, in 2015, more than 50 countries decided to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank led by China. Beijing has a stake of approximately 30% in the new institution.

In recent years, China has become a potential competitor to the western liberal democracy and has been evolving into a soft-authoritarian state. The Chinese development model, which includes a strong role for the state, a focus on investment and export-oriented economy has produced around four decades of phenomenal growth. However, there has been a noticeable slowdown ever since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.

In the Photo: China Traffic, Photo: Denys Nevozhai/ Unsplash

In the Photo: China Traffic, Photo: Denys Nevozhai/ Unsplash

The Chinese Development Model mainly incorporates political and economic policies of China that were instituted by Deng Xiaoping after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. These policies have further contributed to China’s economic miracle and growth in Gross National Product. Joshua Cooper Ramo, the CEO and Vice Chairman of Kissinger Associates and bestselling author, coined the phrase ‘Beijing Consensus’ (the title of his book, published in 2009) for the development model for developing countries meant to be an alternative to the Washington Consensus of market-friendly policies promoted by the IMF and World bank.

Daniel Bell, an American sociologist, and Harvard professor (died in 2011) has argued that westerners tend to divide the political world into ‘good’ democracies and ‘bad’ authoritarian regimes. However, the Chinese political model does not fit clearly in either category. Over the decades, China has evolved a political system that can best be described as ‘Political Meritocracy’.

In 1975, Deng Xiaoping, called for four modernizations at the Fourth National People’s Congress. In 1992 the official goal of Four Modernisations was replaced by the formulation of a ‘socialist, modernized country which is wealthy, powerful, democratic and civilized’. His development doctrine was officially recognized as the theoretical basis for China’s reforms.

Deng Xiaoping’s reforms have been extensively accredited for their stress on pragmatism, gradualism, rationalism, downplaying of revolutionary ideology, and the central role of the state in regulating China’s economy. One of the prominent aspects of his perspective on development is a prioritization of science as the source of pragmatic knowledge and absolute truth.

The new development paradigm claims to prioritize ‘people-centered approaches to development’ and social harmony in contrast to the stress on economic growth.

Chinese State-led development model

In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, Beijing has used active state-initiated programs to promote growth and ameliorate the injustices inflicted by the unbridled market. According to Pan Wei, a New Left Scholar, the China model defends the state-owned economy and its vested interests as advanced economic management without the constraints of the Western value package.

The Chinese development model has followed the East Asian government-led development model in which industrial policy plays a central role in directing economic development. The elite bureaucracy in China, like that in the East Asian developmental states, has actively intervened in the economy by guiding, disciplining and coordinating the market in order to achieve its economic development goals.

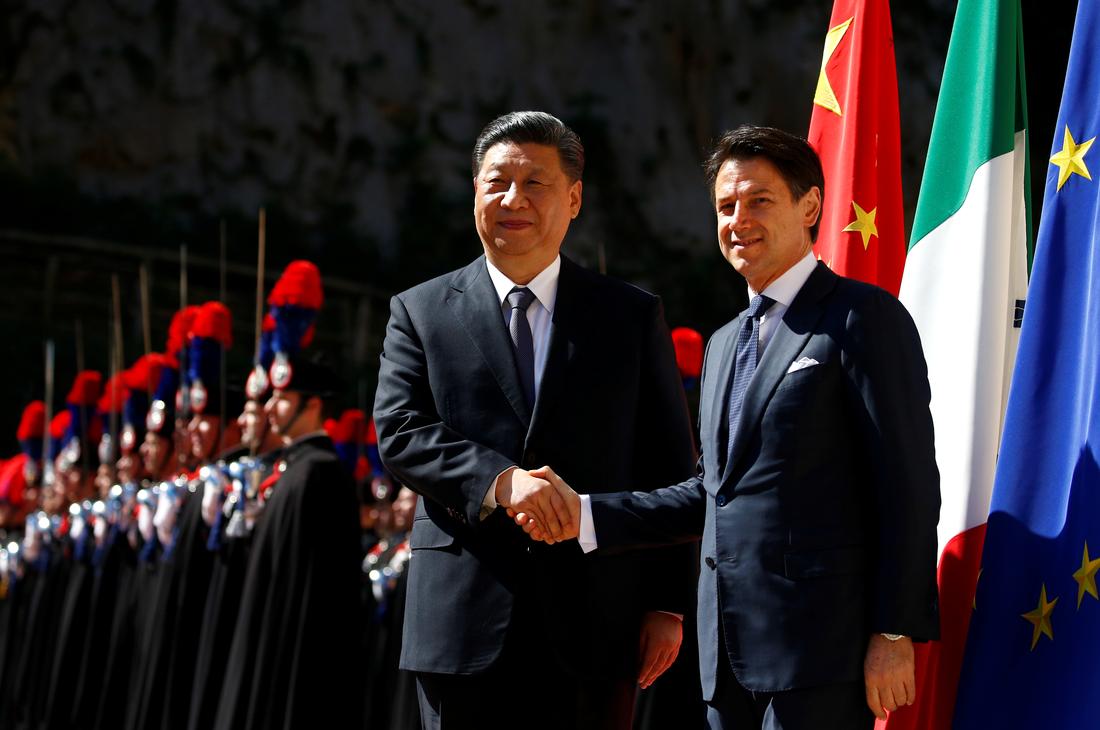

Xi Jinping, China’s party chief, sees no contradiction in pursuing deeper market reforms to achieve his national objectives while implementing new restrictions on individual political freedom. In fact, he sees this as the essence of “the China model” in contrast to the liberal democratic capitalism of the West which he describes as totally unsuited to China.

China has successfully incorporated both decentralization and foreign investment criteria in its development strategy, in order to spur local entrepreneurship and advance international technology standards. Both characteristics particularly shape the development of the auto industry.

There is a growing consensus among Chinese scholars that good governance is pivotal for the establishment of a functioning democracy. The reinvention of the China model through the prism of ‘scientific development’ places China in opposition to ‘developed countries’.

It would not be easy for other countries to emulate all of what China has done. The Chinese development model requires large fiscal resources, technological sophistication, a well-trained and loyal security apparatus, and sufficient political discipline within the regime not to take power struggles public.

China’s development model has made it clear that the state capacity is necessary for ensuring an institutional environment that is conducive to private-sector investments and economic growth. Moreover, in a large economy like China, decentralization serves as a good mechanism for creating appropriate incentives for productive private activities that foster economic prosperity.

China’s path towards economic prosperity requires a modest legal infrastructure at a supra-individual level beyond social relationships, which is centered on the protection of property and contract rights.

One of the major limitations of the China development model was the underdevelopment of the rule of law, which leads to the self-ruling class and rampant corruption. Without democracy and the rule of law, liberation and individual freedom would not be materialized and concretized.

If we look from an economic perspective, the government intervenes too much in the economy and this problem of improper intervention has never been solved ever since the developmental model came up.

A fruitful way to approach the task of Chinese development knowledge production could start with a critical reflection on the complex influences on development thinking and efforts to acknowledge, respect and build on the existing experiences and perspectives.

China’s development model is ‘practicality, hard work, innovation and cooperation’, which seems to be attractive to developing countries. This model has therefore proved that as long as a country’s people work hard, they are bound to overcome poverty and lead a better life.

In the past years, China has invested heavily in the economic development of other developing countries.

As part of the ambitious “One Belt, One Road” initiative, Beijing is funneling billions of dollars into infrastructure projects that will connect the Chinese economy with a host of countries dotted along the ancient Silk Road. According to president XI Jinping, ‘every nation should follow its own developmental path’. The Chinese economy adopted extensive decentralization and a bottom-up approach for its own paradigm of development. But for poor countries, the paths could be different. To flourish and prosper, they should also adopt the best practices of governance that are found in capitalist democracies. In particular, private property rights, rule of law and accountability.