It was nearly two years ago, in December 2019 that COVID-19 first appeared. We went through a global equivalent of some of the Kubler Ross stages of grief from “Denial, to “Anger”, to “Bargaining”, and even “Depression”, but with the important difference we got beyond “Acceptance” and found ways to better able to deal with its explosive spread through a combination of science and preventive measures, such as vaccines and treatment, masks and social distancing, and even Draconian ones such as lockdowns, each of which became recognized and in many cases adopted ways to protect and prevent the worse. We were on the way to “Recovery” and return to some level of normalcy when Omicron exploded on the scene.

To be sure, a fourth pandemic wave feeding on the Delta variant had overwhelmed Europe, but in a sense, it was nothing new, not a “different pandemic”. It was the one we were used to dealing with. So we felt that we were in known territory, moving beyond our “grief” to “Recovery”, more comfortable in getting out and about, going to restaurants, shopping at stores, having dinner with friends, traveling by air, enjoying our favorite sports; in short, social life was on the mend, and economies were showing they could rebound as well.

All this was happening up until November 26th when the World Health Organization (WHO) sounded a frightening alarm: The new virus was not just of “interest” but “of concern”, one we had never seen before, one with many more mutations.

Media outlets around the world quickly headlined the newly named “Omicron” virus as a dire threat, and international, national, academics, and research institutes began scrambling to get a basic understanding of the dimensions of this threat. All this created a fresh new wave of fear and frustration, paralleling our first run-in with COVID-19, with the unanswered question being whether we would be unable or able to deal with it.

A week has passed, and now we learn that Omicron cases had been spreading earlier than thought and that it is highly contagious: cases have been confirmed in 20 countries. As a result, health officials are issuing warnings that vulnerable people should not travel.

Where we are and what we know about Omicron

The unanswered questions are how fast Omicron will spread, how deadly it is, and whether we will be able to summon the science and the will to effectively deal with it.

We do not know much because Omicron has only been on the front burner for about a week. The initial warning came thanks to South African researchers already on the trail of this new variant, trying to figure out why COVID and its variant cases were spiking in a South African northern province, alerted by a private lab called Lancet which had found that tests for COVID-19 were missing Omicron because it was so heavily mutated.

Parenthetically, the global community should recognize South African expert competence, at the same time noting that vaccination rates are low in that country, Southern Africa, and in many developing countries in part due to inequities in vaccine availability.

With the outbreak appearing in many developing and developed countries, Omicron has triggered the highest health alerts everywhere. WHO provides the most complete “current” picture of Omicron, as follows:

- It is not clear whether Omicron is more transmissible (i.e. more easily spread from person to person) compared to other variants, including Delta.

- We do not know whether infection with Omicron causes more severe disease compared to infections with other variants.

- There is some indication that there may be an increased risk of reinfection for people who had COVID-19 with Omicron.

The WHO emergency call and other alerts are generating intensive studies around the world, which are currently or shortly underway to assess transmissibility, the severity of infection (including symptoms), the performance of vaccines and diagnostic tests, and the effectiveness of treatments.

We will deal with Omicron—and the next health threat

Diminution of COVID fears and frustrations has taken a heavy blow. Omicron has forced countries and communities to be on high alert and consider reverting to past defensive measures and so far, the main reaction has been to seal borders and prevent travel to Africa, especially South Africa considered the source of the variant.

For now, the only country that has moved ahead with a specific Omicron-focused measure is Israel. On Saturday, Prime Minister Naftali Bennett announced new emergency measures that banned the entry of foreigners into the country and instituted phone tracking by the country’s domestic intelligence service to locate Omicron carriers. This did not go down well and by Monday, rights groups had petitioned Israel’s top court to repeal the new measures, in particular, the use of counter-terrorism phone tracking technology for the purpose of monitoring Omicron carriers.

Beyond this, the emergence of the Omicron variant has cast a heavy psychological and depressing shadow for many of us. But we also need to keep in mind that COVID-19 has been the impetus for incredible progress. It has generated new science, methods, processes, and tools to deal with viruses—and more.

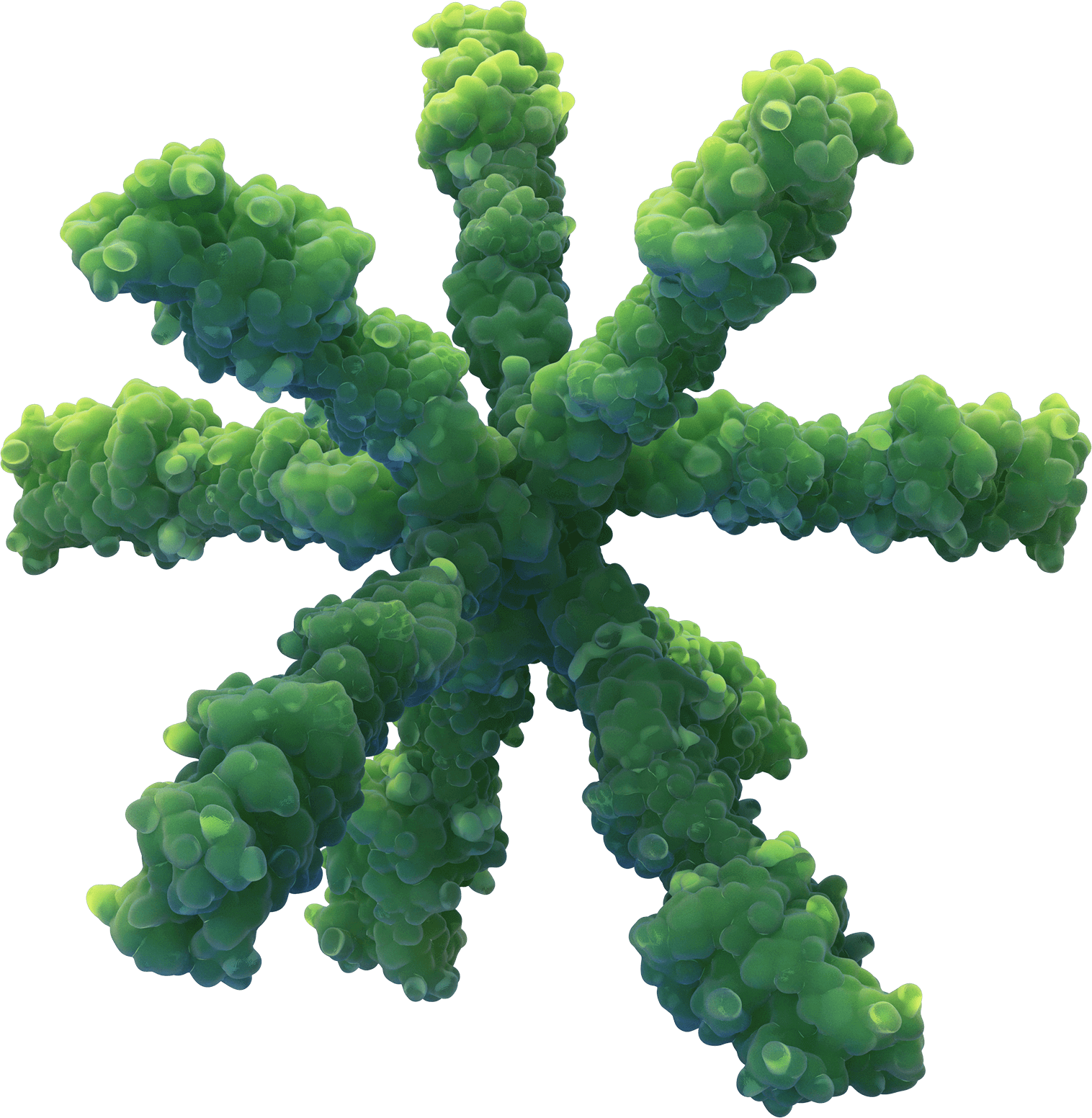

For example, DNA can now be synthesized to a particular antigen on a virus (the spike protein), a technique that would have been barely feasible 10 years ago. One company, Twist Bioscience, synthesizes the longest DNA snippets, up to 300 base pairs to form genes, charging .09 cents a base pair for DNA, which is a tenfold decrease from the industry standard in the past.

Another brand-new company. Ginkgo Bioworks, which only went public in September 2021, uses Twist technology to look at bacterial genomes to generate new antimicrobials. As one chemist with Ginkgo, Tom Keating, put it, “We don’t need to be growing [the organism] on a plate…all we need is the code.”

It is not only the conventional human health industries that are being brought to bear. Diverse fields of science are being engaged. For instance, experts are developing refined computer forecasting models to project the spread of any specific disease. Still in its infancy, this analytical tool will enable us to better get ahead of any outbreaks.

There are many more examples of promising efforts to deal with Omicron and other infectious diseases, which engage veterinary science, sociology, anthropology, and beyond. Some 18 years after the 1918 Spanish Flu global pandemic which killed between 50 -100 million people worldwide, an analysis of veterinary reports by a virologist, Edwin Sharpe, found the link with an unusual outbreak of swine flu, proving that pandemic had been caused by a virus – for the first time.

Consider how far we have come today, and in so doing, let’s put Omicron fears and frustrations in perspective. We will get through this, one way or another, and hopefully, make us better able to deal with other known and future health threats.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Map tracking Covid, as of Dec.1, 2021 Source: NBC news