On Wednesday, thousands of protestors gathered in Brazil to contest a series of anti-environmental laws expected to be voted on in the coming weeks.

The protests, “Ato pela Terra” (Stand for the Earth), occurred after one of the country’s leading musicians, Caetano Veloso, called for a demonstration to denounce the upcoming laws. The event brought together many other artists and roughly 200 non-profit groups.

If approved, the anti-environmental laws would approve commercial mining in indigenous lands, loosen environmental licensing regulations over pesticide use and boost land grabbing and illegal logging in the Amazon — an already pressing issue the Amazon has faced since Bolsonaro took office in 2019.

The bill has been debated in Congress since 2020, but as the Ukraine-Russia war continues, Brazil’s crucial fertilizer supply from Russia has become increasingly threatened and has prompted the administration to take an emergency vote.

The senate is not expected to vote on these laws until the second week of April, leaving time for a task force to review the environmental laws before it is passed, according to speaker Arthur Lira.

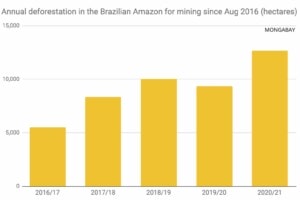

As the Amazon reaches record high deforestation rates, these anti-environmental laws will be a landmark decision in deciding the future of one of the most important rainforests in the world.

Protections have significantly weakened since Bolsonaro took office in 2019

Since Bolsonaro took office in January of 2019, 57 pieces of legislation have been passed that have weakened environmental laws. According to an analysis published in March 2021 by Biological Conservation, a leading international journal in the discipline of conservation science, these pieces of legislation range from relaxing forest protections to declassifying tons of toxic pesticides. The majority of these bills, 27, were passed during the peak of the pandemic — March to September 2020.

Supposedly, Brazilian officials strategically passed these bills during the pandemic as COVID-19 distracted many from other pressing issues.

In April 2020, Brazilian Environmental Minister Ricardo Salles told government officials at a meeting to take advantage of how the “media attention is almost exclusively on COVID… to open the flood gates and change all the rules and simplify the norms.”

Following this statement, in the subsequent months, many environmental protections in place were weakened.

In June 2020, a piece of legislation was passed that no longer made it necessary to restore environmental conservation areas that were damaged from deforestation. In July 2020, 47 pesticides had their toxicity classifications lowered or eliminated altogether.

During the pandemic, the study found the issuance of environmental fines regarding illegal deforestation dropped by 70% even though deforestation in Amazon increased by 9.5%.

Most recently, on February 11, 2022, Bolsonaro published a decree which supports the development of artisanal mining, garimpeiros — a mining technique that simultaneously mines for minerals while promoting “sustainable development.” Although, this sustainable development typically doesn’t happen as artisanal mining incorporates machinery and the building of infrastructure.

Now, the government wants to loosen protections even more and widen the areas for mining and logging to encompass indigenous lands.

Mining has plagued Indigenous people for years now

Gold mining is the most significant type of mining that has had an impact on Indigenous land in the Amazon. As gold mining releases large amounts of sediment into waterways, including the mineral mercury, many of these toxic minerals end up polluting important water sources for the Indigenous population and can lead to mercury poisoning if ingested. Mercury poisoning can cause brain damage and serious irreversible health effects.

Alongside polluting watercourses, gold mining also kills fish that reside in affected streams, spreads disease and overall disrupts the Indigenous people physically and culturally.

One of the many communities affected by gold mining is the Munduruku Indigenous people in the Tapajós basin. A recent study by Fiocruz, a research institution associated with Brazil’s Health Ministry and the World Wildlife Fund, WWF, found the toxic chemical mercury in river fish the Munduruku communities in the Sawré Muyby territory rely on.

The study also found that in three of its villages, 58% of Munduruku residents had unsafe levels of mercury in their blood.

Members of the community who oppose mining on their land have also been threatened and intimidated. On March 19, 2021, armed men prevented a group of Mudrukuru people from docking their boat on their own territory. A few days later on March 25, in the Jacareacanga municipality, miners and their supporters broke into and destroyed the properties of the Wakoborun Women’s Association and other similar organizations that oppose mining on indigenous land.

As indigenous communities are now facing the potential of even more and this time legal mining on their land, this will be detrimental to their livelihood.

At the protest, many indigenous people spoke out against the environmental laws that will target their land — which they refer to as “the package of destruction.”

“We are not going to accept (the extraction of) potassium on Indigenous lands, to pay the bill of those who are killing themselves. Enough Indigenous blood!” Sônia Guajajara, a tribe member and executive coordinator of the Association of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, said to the crowd.

With the continued effort by the Brazilian government — and the current bill being debated — to weaken logging restrictions in the Amazon and to increase mining in Indigenous territory, the Brazilian environment and Indigenous communities have a target on their back that is about to be fired upon.

If these anti-environmental laws are passed, mining and deforestation will significantly increase, affecting the health and land of Indigenous communities and the Amazon rainforest which plays a key role in reducing the impacts of climate change. To make a difference, citizens and activists must continue to protest in what often seems like an impossible fight for hopefully a possible clean and healthy future.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Featured Photo: Deforestated lands in the Brazilian Amazon on October 8, 2020. Source: Bruno Kelly/Amazônia Real, Wikimedia.