How do we tell a story? How do we tell the world about an event everyone has heard of or read about but has not seen firsthand? For Cheryl Diaz Meyer, a Pulitzer Prize Winner photojournalist, all it takes is one click to capture a story. Sounds easy for us, right? But not for her especially as she does not hesitate to put her life on the line. Despite the dangers involved, she still goes to the battlefront (literally or otherwise), so we can see, in the safety of our homes, what is going on beyond those lenses.

As the old adage goes, a picture is worth a thousand words. For a photojournalist, this couldn’t be more true. All it takes is one photo – one – to tell the story.

Cheryl Diaz Meyer, best known for her iconic coverage of the Iraq war and documenting women’s plight around the world, gave us a glimpse of her life as a photojournalist and the work she has done.

You were born and raised in the Philippines and your family decided to move to the United States when you were 13. How was your experience adjusting to a new country?

Cheryl Diaz Meyer: It was not easy. I was happy to be in the US, which held my future, but I missed my friends, my extended family and life in the Philippines terribly. We lived for a few months in Wisconsin and then settled in northern Minnesota, a very homogeneous part of the country. A combination of being a teenager, as well as the area where we lived, I felt a need to fit in, so I stopped speaking Bikol for several years and tried to get rid of everything that felt different in me. A few years later, when I had the need, I could barely utter a word of Bikol and that distressed me. It was through sheer will and effort that I forced myself to speak it again until I regained most of my ability to speak. Through the years, I’ve had to negotiate my own identity in the US and the Philippines. In the US, I am Asian. In the Philippines, I am American. But as a bi-racial woman, I’ve learned to embrace and claim my heritage in all its nuances and complexities.

…my goal was to make images that were truthful and told the story of the war in a powerful way.

Prior to moving to the US, had you already developed an interest in photography? You got your first BA degree in German (University of Minnesota-Duluth) and the second one in Photojournalism (Western Kentucky University), what triggered this change in direction?

When I was a child, my mother used to sit me down with family photo albums and she would tell me about the lives of my aunts and uncles and extended family, and I loved her storytelling. As a teen, I was an exchange student in Germany for a year, where I learned to speak German. So when I started college just after returning from Germany, I naturally started taking German classes and wanted to combine that with International Business. Unfortunately, the concepts of supply and demand held no fascination for me. I realized after two Economics classes that my initial goals were not a good fit.

In The Photo: After the initial days of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, Fatma Mohammad and Zubaida Salman, left and right, greet each other warmly at Al Amtithal Elementary School, the first to reopen in Baghdad. Photo Credit: cheryldiazmeyer.com

I fell in love with photography in a serious manner when a friend invited me on a photo walk, and then she introduced me to the darkroom where I learned about film processing and printing. The magic of the process was mesmerizing. I started to take photo classes along with my German classes. I found myself drawn to photography books in the library and would spend hours by myself among the classics like Henri Cartier Bresson and Diane Arbus. One day, I was looking at a photo book, and I was so overcome with emotion that tears were streaming down my cheeks, and my heart was racing. I remember very concretely thinking, “I don’t know what it’s like to be high, but if this is anything like it, I need this!”

Eventually, a professor who became a dear friend, helped me figure out my next step, which was to attend a photojournalism program. My intention was to do a Masters, but the most renowned school at the time, Western Kentucky University, doesn’t offer a Masters program. So I did a second Bachelors degree.

You won the Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography in 2004 for your poignant photograph depicting violence in Iraq war and in 2006 for your team’s coverage of Hurricane Katrina along with your colleague David Leeson – and you won many more awards since, the latest in 2018 for your coverage of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Can you share with us the story behind these photos?

The 2004 Pulitzer Prize, which I shared with David Leeson, was one of the most difficult assignments of my career. I was embedded with the Second Tank Battalion of the U.S. Marines for a month as they entered Iraq from Kuwait. It was only later that I learned I was the first female to cross the border during the invasion.

At that time, women were not allowed to be on the front lines of battle, so my embed gave me a unique vantage point on the invasion. I was permitted to photograph almost everything I witnessed. But it was physically and emotionally grueling. We would travel for hours riding in a Humvee or amphibious assault vehicle weighed down by Kevlar vests and helmets and gear, and then find ourselves in an ambush. Tragically, several Marines were killed in firefights and many more injured.

Awards were not on my mind as I worked the assignment, my goal was to make images that were truthful and told the story of the war in a powerful way. The Marines were good friends to me, and we suffered together — in cold, heat, dust and terror. I am forever indebted to them for their hospitality and kind welcome.

In The Photo: Myanmar’s Rohingya refugee children are traumatized by the violence they’ve witnessed from the Myanmar army, they wait to board boats in Shah Purideep, Bangladesh, to continue their journey to refugee camps further in the country on Oct. 3, 2017. Photo Credit: cheryldiazmeyer.com

The Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh was a very different kind of story. The situation is not a war, but an assault on helpless civilians. As a journalist, the suffering I saw in the images of refugees fleeing Myanmar to Bangladesh was earth-shattering. I decided on a Friday to cover the story and was on a plane the following Saturday night to Bangladesh.

My quick decision was not without complications. I was held at the airport in Bangladesh immigration for several hours trying to procure a visa. Eventually, I was released and made it to the border area where refugees were arriving. It was overwhelming. Thousands of refugees arrived daily on Bangladeshi shores. And the Bangladeshis were in general kind and receptive to the Rohingya, despite having welcomed many thousands more Rohingya on their shores in previous years. The temperature was blistering hot. My goal was to show the gravity and degree of suffering the Rohingya were subjected to by the Myanmar army and Buddhist vigilantes. The stories they shared were horrific and heartbreaking.

My camera is a weapon and I’ve used it to defend myself.

Which photojournalist or photographer do you admire the most and why?

Generally, I’m not one to idolize people, but I do admire the work of certain photographers. When I was a young photographer, I admired Cartier Bresson’s work, as mentioned earlier. He was a master of blending into a scene to the point where the viewer does not feel his presence in his images. I studied his photos and read his writings to try and understand how to be as a photojournalist. As an extrovert, I learned to listen, quiet my thoughts and observe.

I also admire the work of James Nachtwey. Not only are his photographs deeply moving and aesthetically beautiful, but his immense bravery is evident in his images. I don’t know him personally, but I’ve worked alongside him and he is disciplined and incredibly focused.

Did you have a mentor, and if so, what was the most important thing you learned?

My mentor is also one of my best friends. Her name is Amethel Parel Sewell, and we’ve known each other since we studied together at Western Kentucky University. She is also Filipina, and a talented photographer who diverted to design most of her career. Recently, she started shooting photos again and she teaches classes in San Diego.

As a student, I recall lamenting to her that it was hard competing against the males in our profession and that being small, a woman, and a person of color were a detriment. We have to carry the same amount of equipment and it can often feel like one is working with a handicap.

In the Photo: Myanmar’s Rohingya refugee Anwara Nurhassan, right, takes a boat from Shah Purideep, Bangladesh, as she continues her journey to refugee camps further in the country on Oct. 3, 2017. Photo Credit: cheryldiazmeyer.com

In the Photo: Myanmar’s Rohingya refugee Anwara Nurhassan, right, takes a boat from Shah Purideep, Bangladesh, as she continues her journey to refugee camps further in the country on Oct. 3, 2017. Photo Credit: cheryldiazmeyer.com

To this day, her response resonates: You are a woman, the better to access stories about women and children that your male colleagues cannot. You are an Asian and a person of color, the better to understand the experiences of minorities, immigrants, and refugees. You are small, the better to fit under the elbows of men and their tripods when you have to work side by side with them. These simple words of wisdom impacted me so deeply. Philosophically I realized–I don’t need to be like anyone else. From that time forward, I began to look at all my unique qualities as strengths, and I have found ways to use all of my knowledge and background in my work as a journalist.

All photojournalists risk their lives in conflict zones. Did you find that there are special dangers for female photojournalists? For instance, when German photographer Anja Niedringhaus was shot dead at a checkpoint in Afghanistan?

The death of Anja Niedringhaus had nothing to do with her being a woman, it was simply a terrible attack on a foreign journalist who was also a woman. Indeed, there are special dangers for female journalists. This was particularly evident during the Arab Spring in Egypt where women journalists were brutally sexually assaulted.

When I worked in the Middle East, I often had to endure groping and harassment. It’s certainly very maddening and demeaning as it’s an affront to one’s being. My camera is a weapon and I’ve used it to defend myself. It is so tricky and one has to have a finger on the pulse of the situation.

In The Photo: Northern Alliance tanker Abduwali cheers his fellow mujahedeen as they prepare to take Khanabad and Konduz in northern Afghanistan in the weeks following 9/11. Photo Credit: cheryldiazmeyer.com

Uprisings are prime events for chaos, the mob mentality takes over and it can turn crazy on a dime. My heart breaks for my female colleagues who have had to endure some of the most violent attacks possible in the course of doing their job. I will also say that the abuse we endure as women journalists is not necessarily exclusively the experience of women. My male colleagues have also experienced groping and harassment, although not nearly to the same degree.

We all have a story to tell…that is what makes the images we make unique, in the sense that we are trained in reporting and seeking the truth. We also are telling stories not about our own adventures, but about the people we meet, providing a voice for their narrative.

I know that in Iraq you witnessed the death of a man shot by his friend as a result of a mistake; what is your most unforgettable experience as a photojournalist?

Covering my first battle was unforgettable. I had been following a group of Afghan mujahideen all day long as they hiked deeper and deeper into Taliban territory on Thanksgiving Day 2001. There was supposed to be a surrender of Taliban fighters, instead, a battle ensued.

I was walking down a dusty path when I saw mujahideen fighters running toward and past me, eyes wide with terror. Then bullets started whizzing past my head and mortars were exploding nearby. My poor translator was walking behind me, mumbling to himself. It was all very surreal. I picked up my camera and tried to take pictures, but my eyes would not focus. After a couple minutes, the risk escalated so rapidly I began to run, and as I heard the high pitch of a mortar coming in, I would plaster myself against a mud wall until it exploded, then I’d run again.

When I reached safety, the paradoxical conclusion hit me that we are no closer to life when we are so close to death. For at the moment when there were so many bullets flying, I felt like every cell in my body was ringing with life. It was more than adrenaline, it was an incredible sense of life coursing through my veins.

In The Photo: “I thought, this is my death. I felt no pain.” Iman Eaziden Bakr, 17, raised her chin defiantly, her eyes glistening in the dim light. “I felt like a chicken being roasted. I will never forget the torture of my skin; it was so painful—as if my insides were being exposed.” Her tea had long ago gone cold as she recounted the day on Jan. 14, 2007 when she poured kerosene on her body and set herself on fire. She had hoped that her act of sacrifice would bring peace to her family whom she described as always fighting. Photo Credit: cheryldiazmeyer.com

In The Photo: “I thought, this is my death. I felt no pain.” Iman Eaziden Bakr, 17, raised her chin defiantly, her eyes glistening in the dim light. “I felt like a chicken being roasted. I will never forget the torture of my skin; it was so painful—as if my insides were being exposed.” Her tea had long ago gone cold as she recounted the day on Jan. 14, 2007 when she poured kerosene on her body and set herself on fire. She had hoped that her act of sacrifice would bring peace to her family whom she described as always fighting. Photo Credit: cheryldiazmeyer.com

What a traumatic experience! If I may, I’d like to move to another subject: From your standpoint, how has photojournalism evolved? In the age of Instagram and “extreme tourism”, do you see social media and these new forms of tourism as a threat to photojournalism?

Instagram is a platform I use to share my work, and I don’t ascribe to the idea that social media or “extreme tourism” are a threat to photojournalism. To each her own. We all have a story to tell. Photojournalists abide by a set of ethical rules, and that is what makes the images we make unique, in the sense that we are trained in reporting and seeking the truth. We also are telling stories not about our own adventures, but about the people we meet, providing a voice for their narrative. What is dangerous about social media is that viewers are unable to distinguish between news and personal narratives—and fake news. Companies like Facebook are trying to change the algorithms, cutting off companies known to put out fake news, and changing the presentation of news to viewers.

I know you come to the Philippines fairly regularly, do you see it changing? The Philippines is ranked number 127 in the 2017 World Press Freedom Index. Have you worked as a photojournalist in the Philippines and was there a time in which you felt threatened while on assignment?

I have not been to the Philippines in nine years, but I hope to be back this year for a project. I have worked as a journalist in the Philippines and have found it to be both easy and challenging—easy in that common people are very welcoming, challenging in that the country has a distinct pecking order and bureaucracy. I do find it tragic that the Philippines has such a terrible track record for press freedom. Of course, it’s not helpful when the leadership speaks openly and disrespectfully about journalists. I’ve never personally felt threatened on assignment in the Philippines.

If you’re not on assignment, how is your day like?

When I’m not on assignment for a particular company, I’m still working—and these days I work very, very hard. I started freelancing less than a year ago and there is still much to learn about the business. I’m researching, licensing images, working on contracts, shooting projects, and learning new technical skills.

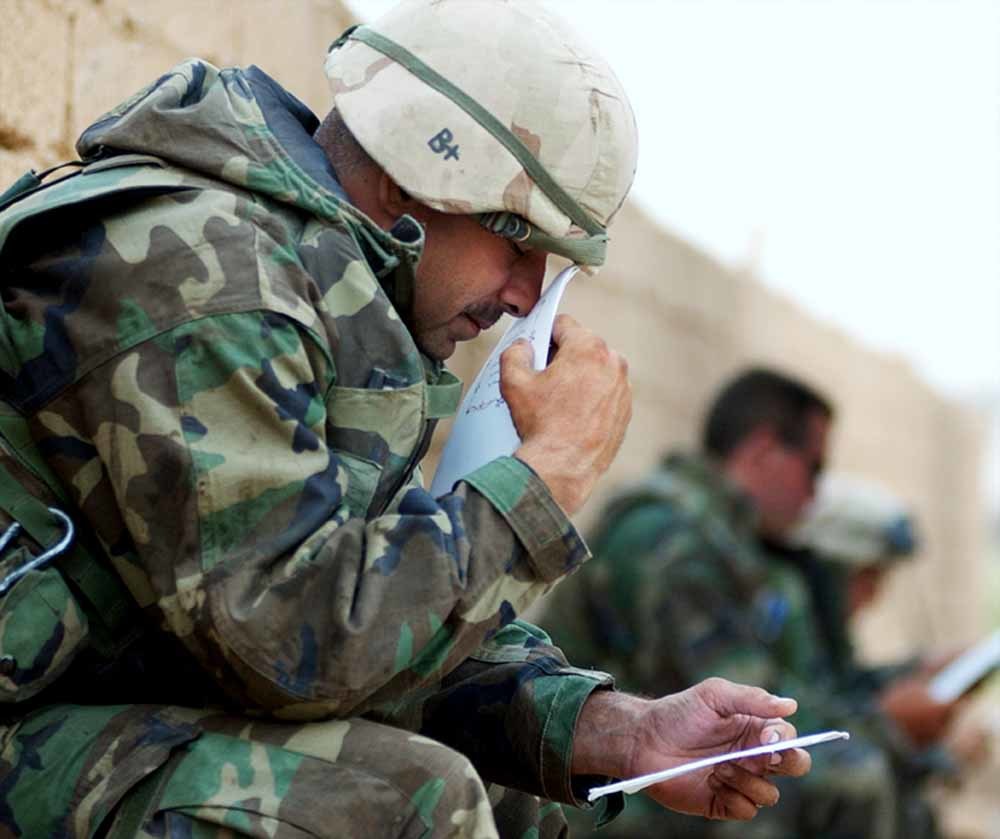

In The Photo: After three weeks and 300-plus miles of speed-and-maneuver warfare, Master Gunnery Sgt. Frank Cordero savors the first letters from his wife, Melissa, on April 7, 2003. “I held that first one for about five minutes…just to smell it and hold it.” Photo Credit: cheryldiazmeyer.com

Besides being a photojournalist, what other activities are you involved in?

I have a family, so we spend time together hiking, baking, traveling with friends, watching movies, swimming, playing. How do you combine your family life with your work? Right now, things are a little imbalanced as I work a lot. This is the problem when you love what you do—it never really feels like work. But I try to take time and be with my family without distractions.

Considering the changing fortunes of print media, what would be your advice to aspiring photojournalists?

I advise young photojournalists to find stories they feel strongly about and tell them visually. Don’t wait for anyone to anoint you, do the work and the rest will fall into place. If you can find a mentor or a colleague you trust, develop a working relationship where you can get honest feedback. It’s hard these days as there are fewer and fewer staff positions, so you have to find a way to grow your skills and tell deeper, more nuanced stories as an autonomous journalist. Finally, don’t be satisfied with what you do, always aspire to be better than what you were yesterday.

You are working as an independent photographer since 2017, what are your plans for the future?

I am working on a project idea that will take me back to the Philippines this year. And I’m learning 360 and VR. So much to do, too little time.

We all have our own way of telling a story. Be it through words or pictures, it’s our own way of telling a narrative and conveying the emotions of our subjects.

So, what’s the story you want to tell?

About Cheryl Diaz Meyer

Cheryl Diaz Meyer is a Pulitzer-Prize winner and an independent photographer based in Washington, D.C. She is best known for her iconic coverage of the Iraq War and her insightful documentation of women facing adversity across the globe. In 2004, she and her colleague, David Leeson won Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography for their “eloquent photographs depicting both the violence and poignancy of the war with Iraq.” She was also awarded the Visa D’Or in 2003 at the Visa Pour L’Image photo festival in France. Aside from being a photojournalist, she is also a visual editor, videographer, producer, writer, and public speaker. Click here to see Cheryl Diaz Meyer’s complete profile.