Following the announcement that Bahrain, too, had decided to enter into the so-called peace deal with Israel, I approached political analyst for the MENA region and facilitator for the UNITAR Masters in Peacekeeping and Post-Conflict Resolution, Dr. Nicolai Due-Gundersen, for a comprehensive analysis of the key narratives and points raised in the media after the announcement of the UAE-Israel deal, and the subsequent announcement that Bahrain too would be joining the deal.

A Good Time for “Peace” Agreements

How narratives of security and peace are utilised is a subject always in need of analysis and alertness, but particularly at this time. As we grapple a global pandemic and as fingers become pointed at the reckless responses to the pandemic — the Trump Administration‘s response in particular coming under fire — it is a good time for “peace” agreements.

Added to this are reports of protests in Israel, as Prime Minister Netanyahu faces accusations of corruption and poor management regarding COVID-19, as well as the fast-approaching U.S. elections. Furthermore, we are seeing the Trump Administration’s efforts to further bully Iran by reimposing sanctions, despite a lack of support from the international community — with many countries declaring that these sanctions are illegal and ineffective.

However, the recent deal with Israel, signed by the UAE and Bahrain, has not received much attention or criticism from the international community either, despite its huge potential to be problematic for the Palestinian statehood.

Whilst there was an agreement between Jordan and Israel in 1994, Jordan maintained a stance toward having a two-state solution, Dr. Due-Gundersen explains. Yet, with the UAE, the narrative instead has been limited to settlements being frozen in Palestinian territory. It is this difference that Dr. Due-Gundersen identifies as being a betrayal — a betrayal, that is, to the “idea of Palestinian statehood.”

Consequences — Good and Bad, but for Who?

There may be other consequences that result from the deal. For example, Dr. Due-Gundersen expressed the possibility that “Washington’s attitude towards what is happening in the region can empower regimes in the region to also just drop the facade.”

He reminded me that the UAE and Bahrain are also two states which survived the Arab Spring. Furthermore, whilst Saudi Arabia would face difficulties in signing an agreement with Israel, they would still benefit from Bahrain’s new relationship with Israel. We previously witnessed Saudi Arabia and Bahrain’s active relationship, when Saudi led a military intervention to suppress unrest in Bahrain during the Arab Spring.

Having Bahrain and the UAE as an ally, base, and bridge to Israel is probably preferred for the Saudis, he says, which corroborates reports that it is Saudis who are behind Bahrain’s signing of the deal — that Bahrain’s political agenda is apparently “dictated” by Saudi Arabia. As for the Arab Spring and how the agreements happening now relate to it?

“We suddenly see a situation where regimes are asking themselves this, ‘The Arab Spring came and we survived — so do we really have to be in touch with the people?’”

Leading on from this, it is also interesting to consider why Saudi Arabia has not signed any deal thus far and whether this will be changing in the near future. Why Saudi Arabia’s “hands” are politically tied, so to speak, is likely connected to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s reforms, Dr. Due-Gundersen explains. With Saudi Arabia currently “opening up” as it implements reforms from its Vision 2030 aspirations — which, whilst cosmetic, could nonetheless be deemed western and liberal — there is already the potential for backlash.

Adding to that, a deal with Israel would be greatly provocative — not just to factions within the religious elite but to the youth of Saudi too, metaphorically “shaking hands with the devil” and invoking an “Arab revulsion,” which could destabilise the already shaky regime.

Ironically, with COVID-19, many of bin Salman’s reforms are now being reversed de-facto, Due-Gundersen adds. Whether they will remain reversed is a subject of discussion.

Another potential consequence is further fragmentation in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). He tells me that this is not the first time the GCC has become divided in opinion. Following the 2017 blockade of Qatar, there was a division that is much like the division we see now.

The UAE, Bahrain, and even Saudi Arabia have shown that they do want relations with Israel and Washington. Whereas Qatar, which seems to have closer ties with Turkey, reaffirmed its support for the Arab Peace Initiative. In Kuwait, according to Cinzia Bianco, senior advisor at Gulf State Analytics, “the National Assembly has capitalized on hostility towards Israel to claim its place as the voice of the people,” thus rendering any relations with Israel difficult.

Whilst Due-Gundersen believes that the GCC, as a form, will remain, he does suggest that it will lose its effectiveness and status as the main security pack for the whole region with the different security packs now being formed. Discussion regarding the Gulf countries becoming a cultural union will also likely come to an end.

Related Articles: US and India and the Indo Pacific | Unpacking the UAE-Israel Deal | The Khashoggi Affair

Another state that may bear consequences from the deals is Jordan, Due-Gundersen predicts. In an analysis regarding this issue, he writes that this “reduced importance for Jordan as a conduit for Arab access to Israel may come with reduced U.S. aid to Amman.”

Furthermore, how Palestinian diaspora, an estimated 2.6 million of whom live in Jordan alone, will react when COVID-19 restrictions are lifted also remains to be seen. The fact that UAE and Bahrain announced their entering into such a deal during the pandemic and restrictions is not a point, however, that has been lost on Due-Gundersen.

He also questions to what extent the deal has succeeded in uniting Palestinian political factions in Gaza and the West Bank, and what kind of opposition, going forward, we may see.

Possible Motivations for Signing the Abraham Accords — Security and Stability

This year I was watching a series of lectures given by Iran’s Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, titled “The World in Transition.” He discusses the problems that are arising from asymmetries in the region, as states look upon these asymmetries from a paradigm perspective which “rests on exclusion, rivalries, zero-sum approaches.” These are asymmetries of geography, population, natural resources, and wealth in comparison to stature and power. Essentially, there are states in the region that rely more on the outside world, buying security rather than producing it. Zarif concludes that such asymmetries produce tensions in the region that create a misplaced need for such “protection.”

Relating this to the UAE and Bahrain, such narratives of stability and security are being used to justify their decision to begin normalising relations with Israel. Although, such narratives should not be conflated with the narrative of peace.

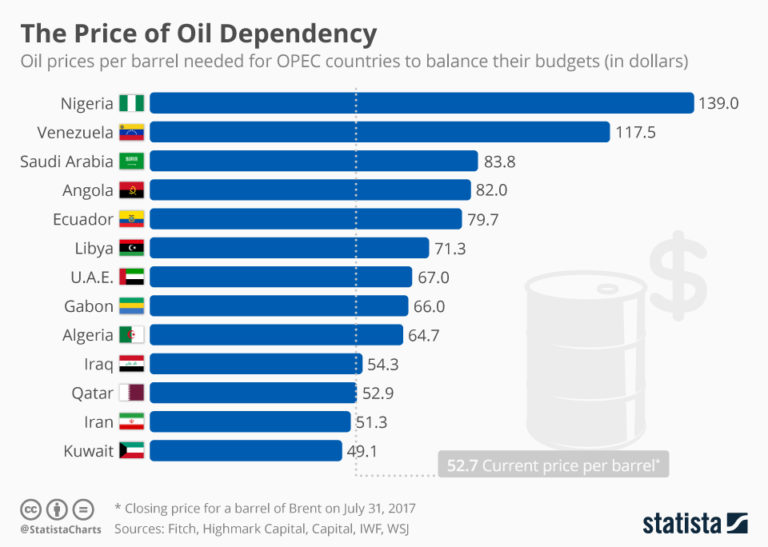

What we see, much like Zarif’s observation, is a desire to balance wealth-stature. To ensure security and potentially to address natural resource deficiencies. Curious about the extent to which concerns, such as food insecurity, may have contributed to the signing of these deals, I put the question to Dr Due-Gundersen.

He responded by pointing to the Qatar blockade. One of the issues this provoked, he says, was how to import food. Such a question has promoted, to an extent, agriculture. It is plausible to suggest that Bahrain, which imports 94% of its food, may have also had these considerations, he concludes. Whatsmore, UAE and Bahrain in February 2020 signed a Memorandum of Understanding to exchange expertise, studies, and research related to food security after Bahrain was rated 50th on the Global Food Security Index (GFSI) and the UAE 21st.

This reliance on food imports is also what distinguishes the Gulf countries and Jordan from, for example, Turkey, which is a country with a huge manufacturing industry, Due-Gundersen explains. Also relevant is that Turkey, along with Iran, was shown to be supporting Qatar with food exports following the blockade.

Due-Gundersen also posits that food insecurity over the next ten years may increase in Qatar, as with other small states in the region, and questions to what extent they can continue heavily subsidizing food products with limited oil reserves. By joining with Israel, and by extension Washington, there is the possibility of pushing for subsidized food imports or making more sustainable deals. For the governments to survive in Gulf states, they must be able to provide for the people, Due-Gundersen says, having created to some extent welfare states with a certain level of expectation.

The narrative regarding Iran has also been ever-present in media coverage following the signing of the deal. According to Due-Gundersen, claims of paranoia about Iran being a motivating factor for signing the deal ring more true with Bahrain.

Last year, for example, Bahrain accused Iran of “stoking militancy” following Bahrain’s execution of two Shia activists. Due-Gundersen explains that such paranoia is linked to Iran being the only Shia majority country which also has a Shia government. Bahrain, however, has a ruling Sunni minority with a majority Shia population.

The apparent threat of Iran, according to Due-Gundersen, is largely ideological. We too should be mindful that we are only observing the public discourse, and cannot know what is really happening behind closed doors, he reminds me and puts forward the possibility that the Gulf countries, knowing the extent of U.S. paranoia toward Iran, could be getting on the bandwagon, so to speak, to gain access to Washington.

What will come next is unknown, and Due-Gundersen says that it will depend on how successful the deal is, how active it is — to what extent it leads to actual good relations between the states. A successful deal may, for example, embolden the U.S. in their policy toward Iran, although war would be an undesired outcome for the “last stable bastion in the Middle East.” Whilst the U.S. may be turning its attention to Asia and the Indo-pacific theatre, as spoken about by analyst al-Khouri, an unstable Middle East would hinder access to Asia, Due-Gundersen concludes.

With all this though, what is most apparent is that of all the players involved and the motivating factors which have brought them to this point, it is unlikely that a genuine desire for Palestinian statehood was rated that high on their agendas.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com

In the Featured Photo: President Donald J. Trump, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bahrain Dr Abdullatif bin Rashid Al-Zayani, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Minister of Foreign Affairs for the United Arab Emirates Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan Signs sign the Abraham Accords Tuesday, Sept. 15, 2020, on the South Lawn of the White House. Featured Photo Credit: Official White House Photo by Joyce N. Boghosian