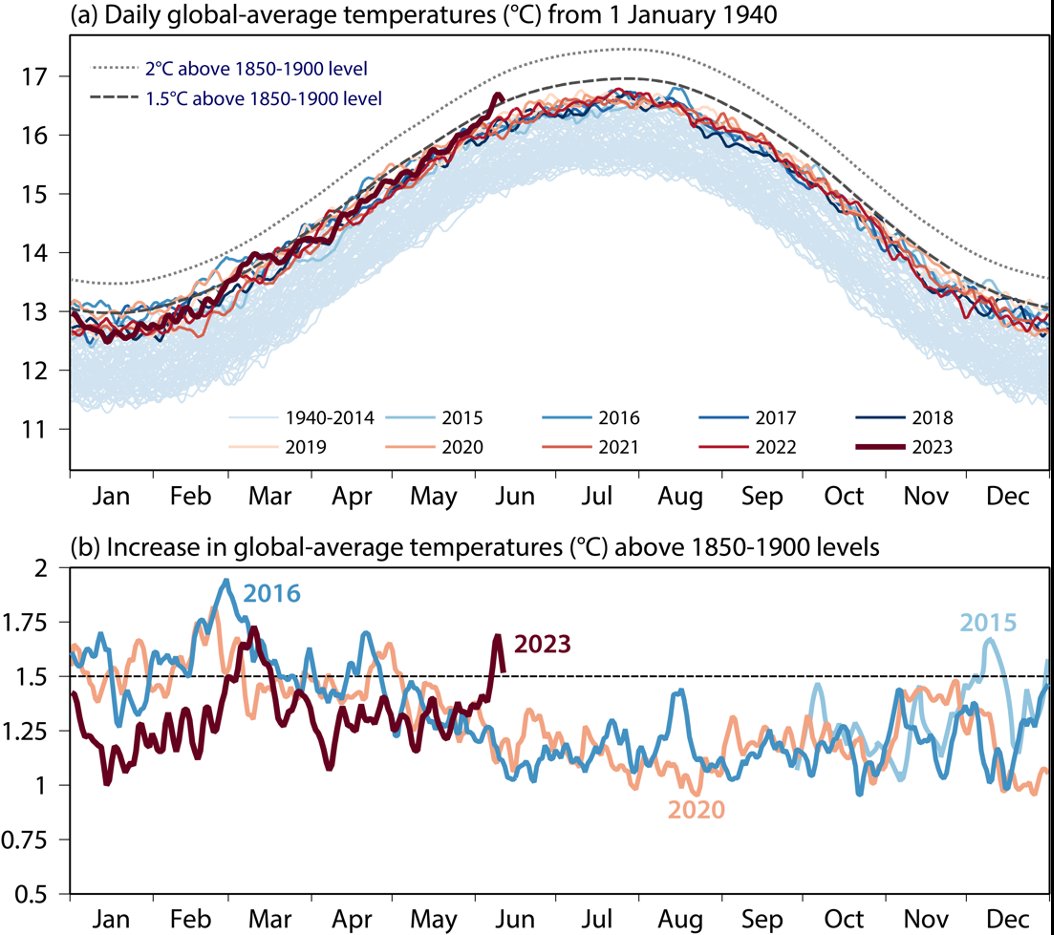

On June 15, the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service reported that global-mean surface air temperatures reached 1.5°C higher than the pre-industrial temperatures for early June, a breach of one of the significant global warming benchmarks set out in the Paris Agreement.

Although a temporary breach of the 1.5°C limit has happened before in 2015, 2016 and 2020, this is the first occurrence of such a breach during the Northern Hemisphere’s meteorological summer, which runs from June 1 to August 31.

Although this sounds catastrophic, what does it really indicate about the current state of the climate?

Will an El Niño year breach the 1.5°C threshold?

In May, the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) warned that the world was almost certain to see new heat records set between now and 2027.

The WMO reported a 66% likelihood of exceeding the 1.5°C threshold in at least one year between 2023 and 2027.

So far, 2016 – the hottest single year on record – was closest to exceeding that limit, with a global-mean surface air temperature about 1.3°C higher than pre-industrial averages. However, 2016 will likely lose that record soon, since the WMO also predicted a 98% likelihood that at least one of the next five years will be the hottest on record.

For each year from 2023 to 2027, the global near-surface temperature is predicted to be between 1.1°C and 1.8°C above the pre-industrial average.

The WMO’s prediction of record high temperatures is due to the El Niño event that is currently being observed in the tropical Pacific. El Niño – an episodic oscillating weather pattern that affects the global climate – is associated with higher than average global temperatures.

The most recent El Niños took place in 2014-2016 and 2018-2019. The 2014-2016 El Niño resulted in the first breaches of the 1.5°C threshold – in December 2015 and February/March 2016 – and the overall high temperatures that caused 2016 to be the hottest year on record.

After the first two breaches in 2015 and 2016, early 2020 was the last time the average global temperature rose to more than 1.5°C higher than the pre-industrial average temperature for the same part of the year.

Although the WMO’s warning about rising global temperatures is broadly in line with similar findings issued by the IPCC’s latest report, the WMO prediction is unique because it is based upon long-term weather forecasting rather than future greenhouse gas emissions.

However, it is significant that the findings from both organisations, despite being formed on the basis of different evidence, project similar pictures for the future of our climate.

Upon release of the WMO report in May, Prof Petteri Taalas, the secretary general of the WMO, said:

“This report does not mean that we will permanently exceed the 1.5C specified in the Paris agreement, which refers to long-term warming over many years. However, WMO is sounding the alarm that we will breach the 1.5°C level on a temporary basis with increasing frequency.”

Related Articles: Global Warming: We Are Dangerously Close to Breaching the 1.5°C Limit, Scientists Alert | UN IPCC: Leaders Urged to Heed Science and Act Now to Avert Climate Catastrophe | Heat Levels Expected to Reach Record Highs in the Next 5 Years: Are We Prepared?

Breaching the 1.5°C threshold: Have we run out of time?

In recent weeks, extreme heat has affected the Northern Hemisphere, fuelling the wildfires in Canada and causing parts of the UK, usually notorious for its abundance of rain, to implement water rationing.

Also notably in the UK, this heatwave ended the “June 13th Enigma,” a meteorological phenomenon stretching back to 1870. Until 2023, June 13 was the only day of meteorological summer to have never recorded temperatures at or above 30°C in the UK.

13th June enigma has come to an end!

Bridgefoot, Cumbria is the first place in the UK to record 30°C on 13th of June.

Now all days of meteorological summer have reached the 30°C mark.

— UK Weather Updates (@UKWX_) June 13, 2023

Although 30°C is not a record high in the UK, it demonstrates what is record-breaking at a global level about this early-season heat wave – it has never before been this much warmer than “normal” at this time of year.

The year 2023 saw the hottest early June on record, with the global average topping out at more than 1.5°C higher than pre-industrial average temperatures for this time of year – echoing the WMO’s prediction that we will start to see this threshold crossed more and more often.

Since 2015, the 1.5°C threshold has been an internationally recognised benchmark for global warming, since the terms of the Paris Agreement set out to limit warming to 1.5°C or, at most, 2°C, compared to pre-industrial levels.

It is understood that if the permanent temperature increases goes above this range, the consequences of climate change will be far more serious and likely to cause irreversible damage to ecosystems around the globe.

However, this temporary breach does not mean that the world has already overshot the 1.5°C threshold.

The 1.5°C limit described in the Paris Agreement is a target for the average temperature of the planet over the twenty or thirty-year periods typically used to define climate.

As mentioned above, June 2023 now marks the fourth time the world has seen temperatures temporarily breach the 1.5°C benchmark. Nonetheless, it is significant because it is the first time that it has happened during the boreal summer.

Until now, extreme variation in seasonal temperature has been more common in the winter and early spring, due in part to the fact that the extreme variations of temperature in the Arctic are most pronounced at that time of year, due to sea ice now melting sooner and faster after the winter.

A breach of the 1.5°C limit in June indicates not only that instances of these extreme variations are continuing, but also that the “season” for unseasonably hot temperatures is getting longer. In the past, meteorologists saw unseasonably warm temperatures only from December to April, but now, that window for extreme variation in temperature is widening, which means these threshold breaches will likely occur more often.

It still remains to be seen how often, for how long and by how much the 1.5°C limit will be surpassed in the coming twelve months or so, as the current El Niño completes its cycle.

Nonetheless, as global-mean surface air temperatures continue to rise and more frequently breach the 1.5°C limit, the cumulative effects of each overshoot will become increasingly serious. As they become longer and more frequent, these temporary breaches will eventually transform into a permanent overshoot of the only barrier between us and climate breakdown.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: The sun appears burning red. Featured Photo Credit: Craig Manners.