In the race to net-zero, companies are investing in carbon offsetting schemes to mitigate their greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon offset schemes allow companies to invest in environmental projects in order to balance their own carbon footprints, and as an effortless way to get closer to net-zero emissions. But, how reliable is carbon offsetting really? And, are companies measuring their carbon footprints accurately?

Effectiveness and the (voluntary) carbon market

When you hear the words “carbon offset”, think about the term “compensation”. Essentially, carbon offsets are reductions in GHG emissions that are used to compensate for emissions occurring elsewhere. They are measured in tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalents and are bought and sold through international brokers, online retailers, and trading platforms. CO2 is considered the most important GHG, due to the dependence of world economies on fossil fuels, since their combustion processes are the most important sources of this gas.

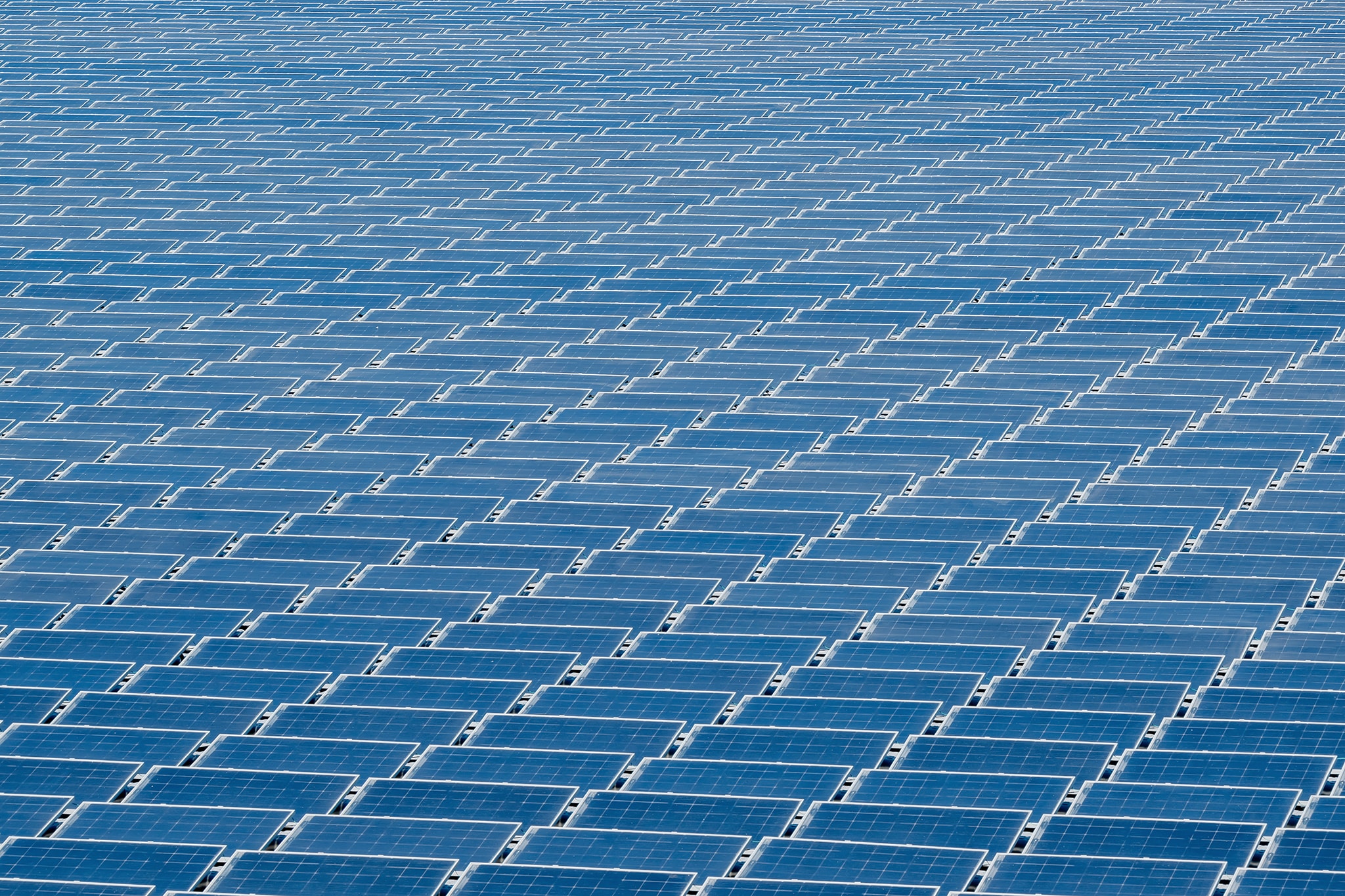

The practice of carbon offsetting allows firms to buy credits from less carbon-intensive companies and organizations to cancel out their own emissions, effectively bringing them closer to net zero. Offsetting methods include reforestation projects and renewable energy sources like wind turbines and dams.

According to an analysis by Morgan Stanley, “yearly removals would need to double, to about 1 gigaton of CO2, by 2030 and accelerate to a 5-gigaton annual pace by 2050 for the world to reach net-zero by that time.” At this point, it’s still far too small to make a sizeable difference.

Yet, today, Gabon, the second-most forested nation after Suriname, targets to create 187 million carbon credits, almost half of which may be sold on the offsets market in what would be the “single largest issuance in history.” The number of carbon credits Gabon aims to sell on the market could be worth about $291 million based on the average price for similar projects calculated by Allied Offsets, a carbon offsets data provider.

At the moment, many businesses worldwide are focusing on natural offsettings, like the case of Gabon. Morgan Stanley predicts that technology-based offsetting would outpace nature-based solutions after 2030. This includes offsets of renewable energy sources, carbon capture, and direct air capture. Carbon capture and storage is a key climate change mitigation technology and is currently in the process of being demonstrated worldwide.

Carbon offsets have developed into a $1bn market. But, at the same time, banks and regulators have been expressing “growing concern” about the sincerity of offsets as a commodity.

Carbon offsetting comes in two varieties: regulated and unregulated.

The EU’s emissions trading scheme is the largest and raised $34bn in 2021. Companies, on the other hand, turn to the voluntary, unregulated, offset market to meet their carbon targets. Even though the voluntary carbon market is one way of combating climate change, it doesn’t convince everyone, and certainly not the banking world:

“[The] voluntary carbon market is the ‘wild west of carbon markets,” investment bank Credit Suisse said in a May report. “It is a self-regulated market with poor transparency.”

Some of the main criticisms the carbon market receives are the lack of regulation and transparency. Many groups are advocating for more transparency surrounding offsets, such as CarbonPlan, a public-benefit nonprofit corporation, that finds that the existing information does not provide an adequate basis for characterising a company’s carbon offsetting strategy.

Carbon offset disclosures have the potential to help investors and the general public to track the climate claims companies make, however, at this point, the system has its limitations.

However, the carbon market does have several principal organizations safeguarding the offsetting practice.

The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) is a global governance body set up in September to establish standards for the voluntary carbon market. The council’s main objective is to “set a benchmark for quality carbon credits”. According to the Integrity Council, these standards will be issued in the fourth quarter of 2022.

An additional leading company in the voluntary carbon market is Verra, providing a standard for certifying carbon emissions reductions. Verra establishes the core rules and requirements that must be met for any project, program or activity to be certified, the independent assessment, the methodologies, and the registry of projects programs or activities.

Lastly, another key player is Gold Standard, established in 2003 by WWF and other international NGOs to “ensure projects that reduced carbon emissions featured the highest levels of environmental integrity and also contributed to sustainable development.” The company has established its Global Goals, a standard that sets requirements to design projects for maximum positive impact on climate and development – and to measure and report outcomes in the most credible and efficient way.

To be noted: There is a difference between establishing standards (a needed first step) and ensuring that they are followed. To monitor real progress toward carbon offsetting, evaluations need to be carried out: Businesses that claim that they are following standards need to be verified by independent experts that are fielded to evaluate and calculate the offsets. The above organisations have all announced that they are carrying out independent assessments.

Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions

A company’s carbon footprint, also known as Corporate Carbon Footprint (CCF), is usually the first step toward carbon neutrality, because, without transparency about its own emissions, it is impossible to define realistic goals and climate strategies.

An increasing number of companies are pursuing ambitious carbon reduction targets towards carbon neutrality. However, a systematic reduction of greenhouse gas emissions is only possible if emission-intensive hotspots can be identified and quantified.

The Corporate Carbon Footprint includes all emissions that are influenced by a company’s decision. This means that in addition to direct emissions, all indirect emissions are also included.

Companies have predominantly focused on Scope 1 emissions, which are defined as the “direct GHG emissions that occur from sources that are controlled or owned by an organisation,” and Scope 2 emissions, which are “indirect GHG emissions associated with the purchase of electricity, steam, heat, or cooling,” according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

However, the Scope 3 emissions are not to be missed. Scope 3 emissions are the result of activities from assets not owned or controlled by the company, but that the company indirectly impacts in its value chain.

Scope 3 covers everything from employee travel to business partners to a firm’s lending and investments – unlike Scope 1 and 2 emissions from a company’s direct operations and power usage.

For many companies and industries, Scope 3 is by far the greatest percentage of total emissions. In consumer goods manufacturing or financial services, combined Scope 1 and 2 emissions represent less than 10% of total emissions. In other sectors, Scope 3 emissions are more than six times the level of Scope 1 and 2 emissions, according to an analysis of Forbes.

But, despite its importance, reporting on Scope 3 is often poor or nonexistent.

One of the main reasons for that is the number of partners in the value chain. And, the calculation of Scope 3 emissions and its impacts is also highly complex.

Reporting on Scope 3 emissions is for major corporations a challenging task, but this does not take away its significance. According to energy transition experts, “many businesses have more than 70% of their carbon footprint coming from Scope 3 emissions.”

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) recently proposed a rule that would require publicly traded companies to disclose climate-related financial information. In particular, if the proposal would be approved, it would require public companies to disclose to investors the company’s Scope 3 emissions, disclose what their sustainability goals are and how they’re meeting them, and outline how climate change is affecting their business.

According to the Commission, the disclosure rule could combat an “enormous amount of greenwashing.” While many companies are trying to do the right thing, greenwashing still remains a problem.

In sum, despite the current lack of regulation and transparency in the carbon market, the practise of carbon offsetting does allow firms to buy credits from less carbon-intensive companies and organisations to cancel out their own emissions, effectively bringing them closer to net zero.

At the moment, market participants are actively working on establishing the best practices for the carbon offset market. And, if a company wants to measure its actual carbon footprint, it should include all of the company’s emissions: without transparency about its own emissions, it is impossible to define realistic goals and climate strategies.

After all, the moment is “now or never” for companies to implement policies that will effectively and swiftly cut down carbon emissions globally.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Aerial view of the Amazon rainforest, near Manaus, the capital of the Brazilian state of Amazonas, covered almost entirely by the Amazon rainforest. Featured Photo Credit: Neil Palmer/CIAT.