Air pollution is often referred to as the silent killer, claiming over 7 million lives annually. Recent reports are putting air pollution in the spotlight however, as the extent of its morbidity is revealed. Unfortunately, reports also show development in African countries is set to increase pollution as cities grow, threatening health infrastructure, child development and the economy.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 9 out of every 10 people lived in areas where concentrations of dangerous particulate matter exceeded 2005 air quality guidelines in 2019. In September, the WHO slashed these guidelines for annual average exposure from 10 micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m3) to 5 as the danger of this material becomes more clear.

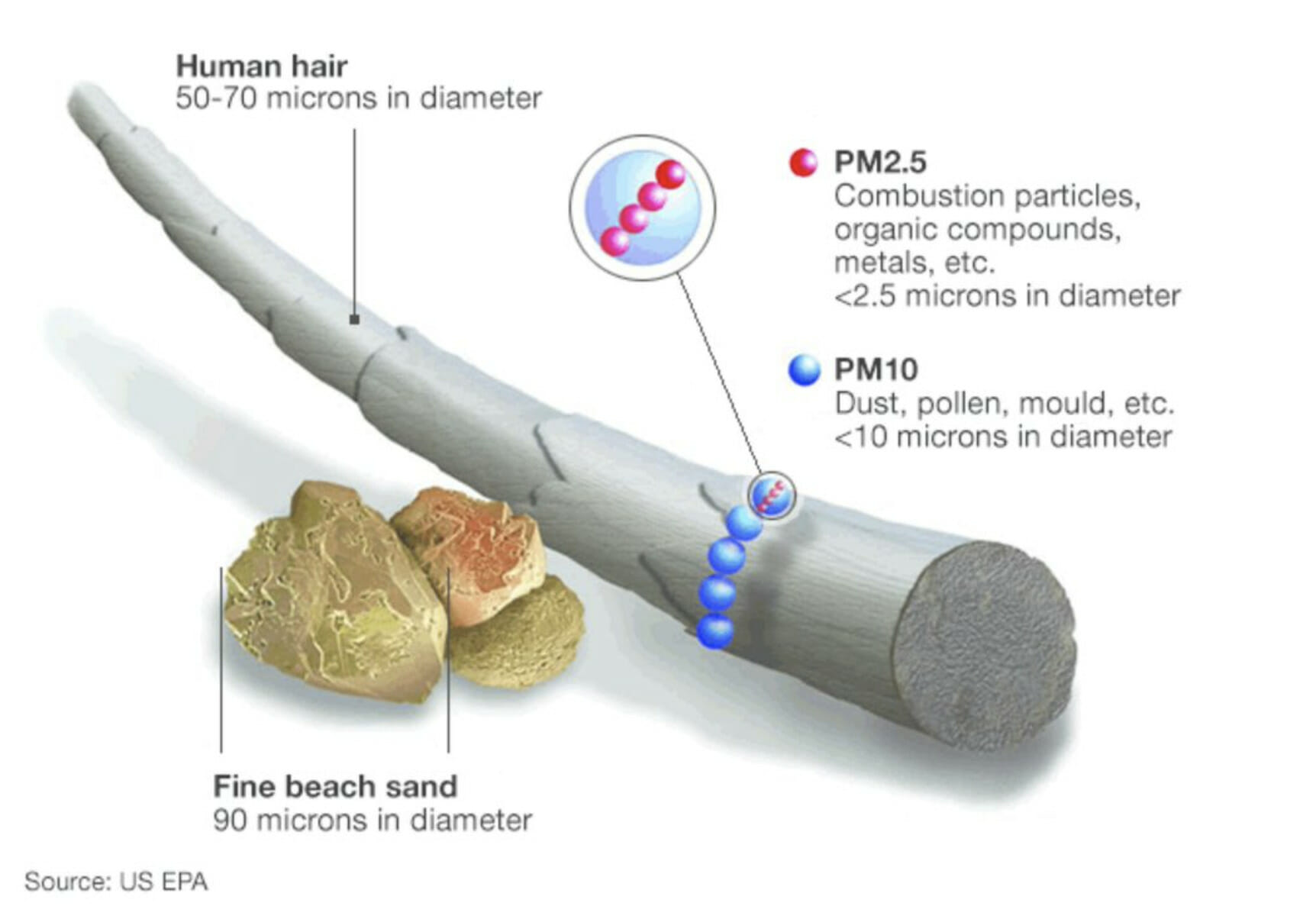

Particulate matter – also known as PM2.5, as it measures less than 2.5 microns in size – is invisible to the naked eye and small enough to pass into lungs, through the bloodstream and into organs. Exhausts, the burning of fuels and other industrial processes have littered the Earth’s air with the particles.

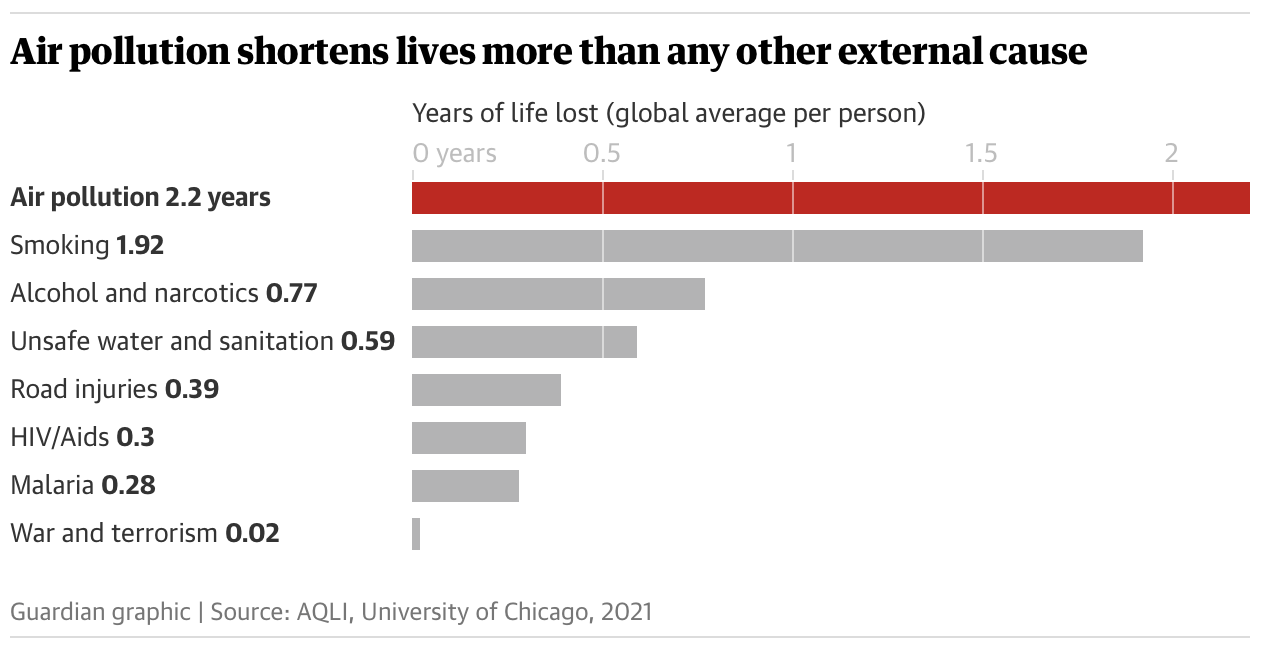

In 2018, one in five deaths were a result of air pollution caused by the burning of fossil fuels. Air pollution killed more people in 2019 than the entire population of New Zealand and Botswana, combined. It doesn’t just kill people though, it slowly shaves years off of everybody’s lives. Data suggests that the average human loses 2.2 years of life due to the current levels of air pollution. Added up that accounts to 17 billion years lost.

Air pollution is the largest environmental or external threat to human health. A 2019 review found air pollution may damage every organ in the body, leading to dementia, heart and lung diseases, the loss of eyesight and stunts intellectual development.

Tackling air pollution starts at home

Across Africa, air pollution has become the second leading cause of death, only second to AIDs. In some regions like the Niger Delta, air pollution can slash lifespans by almost six years.

Claiming 1.1 million lives across the continent, a large portion (700,000) of the deaths in Africa are related to household air pollution which is driven by the burning of dangerous cooking fuels.

3 billion people across the world, including the majority of Africans, rely on fuels like wood or charcoal for their cooking needs. The incomplete combustion of these fuels produces black carbon, a deadly PM2.5 linked to numerous diseases and a significant impact on the climate.

Beyond the risk of non-communicable diseases, these energy sources also demand hazardous open fires and timely fuel collection. The burden of collection primarily falls on women and children and puts them at risk of musculoskeletal injury and violence, reduces opportunities for income generation or education and further entrenches gender inequalities.

For these reasons, universal access to clean cooking was enshrined in Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7) “to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy”. As a result, progress has been made and deaths related to household air pollution have declined slightly but unfortunately not enough.

Recent projections suggest that in 2030 just under 1 in 3 people will still be using polluting fuels for cooking. In sub-Saharan Africa, over 1 billion people are set to be using polluting fuels by 2025 as progress towards cleaner cooking hasn’t kept pace with population growth.

Household air pollution can be reduced through access to cleaner cooking stoves, sustainable fuels and increased ventilation. Considering the health, gender and environmental impacts of household pollution, it is an area that demands increased attention. Various charities such as Clean Cook Alliance are leading this charge, but more effort is needed.

However, even if the 700,000 African lives claimed by household pollution every year can be reduced, there still remains the challenge of outdoor air pollution which is increasing as cities grow and develop across the continent.

Related Articles: Three-Quarters of World Governments Fail to Provide Transparent Data on Air Pollution| The Most Successful Air Pollution Treaty You’ve Never Heard Of

As African cities grow, so does air pollution

Africa is experiencing a massive transformation as the population is set to more than triple by the end of the century. Life expectancy has almost doubled, economies are growing and cities are expanding. These developments are welcomed but they might also be dangerous. The complexity of allowing poorer countries to develop amidst a growing climate crisis has been a defining issue of climate negotiations and it’s clear why.

Unless they are sustainably planned, cities present a massive threat to the environment.

Cities consume 78% of global energy and produce over 60% of emissions, trapping pollution and exposing it to billions. As cities across Africa grow, so could the death toll from ambient air pollution (AAP).

“Experience from other countries suggests that the increases in AAP appearing in Africa today could be the harbinger of a looming problem,” according to a recent report. “In the absence of visionary leadership and intentional intervention, AAP could become a much larger cause of disease and premature death than at present and could pose a major threat to economic development.”

The report highlighted the economic costs of air pollution, noting air-pollution related disease cost Ethiopia $3 billion in 2019. Air pollution damages economies due to direct health infrastructure costs, as well as labour lost and brain drains. Talented and successful workers may leave cities or countries to avoid dirty air, in Beijing this is known as “smog migration”. Furthermore, researchers have found that air pollution exposure in infancy has led to a loss of 1.96 billion IQ points across Africa.

For too long air pollution has been a neglected topic. Recent reports have propelled it into the spotlight as the health and economic impacts become clearer. Air pollution in Africa is a global concern and must be highlighted at the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26).

We encourage Africa’s leaders to take advantage of the fact that their countries are still relatively early in their economic development and to transition rapidly to wind and solar energy, thus avoiding entrapment in fossil-fuel-based economies… We argue that African countries are in a unique position to leapfrog over mistakes made elsewhere and to achieve prosperity without pollution.

– Professor Phillip Landrigan who led the Lancet report

COP26 must recognise the significance of air pollution

After 15 years, it was necessary that WHO quality guidelines were updated. However, these guidelines are voluntary, and a recent UN Environment Programme (UNEP) report has found that one third of the world’s countries have no legal limits in air pollution. Furthermore, funding for air quality is nowhere close to matching the scale of the problem.

Despite being the world’s biggest environmental killer, only 1% of global development aid goes to tackling air pollution. Disturbingly, governments actually gave 20% more in funding to fossil fuel projects which caused the pollution.

Air pollution & climate change are the biggest environmental threats to health.

Achieving these 🆕 @WHO guidelines levels helps protect our health & mitigates climate change: https://t.co/3a9Aas4yIb#BeatAirPollution pic.twitter.com/qvWtnS5wj9

— UN Environment Programme (@UNEP) September 23, 2021

It is clear that air pollution must be a key focus at COP26 in November. The Lancet report has provided clear recommendations to tackle air pollution in Africa, calling for:

- Increased investment in clean, renewable sources of energy

- The explicit prioritisation of air pollution prevention and control

- The allocation of sustainable, long-term funding for air pollution control

- Improved data collection and quantification to accurately assess and apportion areas which pollute the most and require the most funding

- Regulation of household and corporate burning of waste and restriction of agricultural burning

- The promotion of research and research capacity on air pollution, human health, and the economy in African research institutions

Others, such as Prof Michael Greenstone who developed the Air Quality Life Index (AQLI) with colleagues, have suggested that air pollution must be explicitly recognised as “ the greatest external threat to human health on the planet.” If the threat was acknowledged, it could open the way for coal to be accurately priced with health costs embedded, forcing the fuel to become uncompetitive.

COP26 presents a uniquely significant (and possibly final) opportunity for leaders to implement real change. As the environmental and health implications of air pollution become clearer and more pressing there is no doubt that it can be ignored. Hopefully, air quality will be brought to the forefront of health policy discussions and will no longer remain the silent killer.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Smoke is polluted into the air from factories. Featured Photo Credit: Maxim Tolchinskiy