Civility is crucial and can change lives as Sydney Poitier, the great Bahamian-American actor who died last week well knew. He had managed the feat of breaking Hollywood’s racial barrier, and when asked the reason for his towering success, he said the most important advice came from his Mother: Always say “Please” and “Thank You”.

He kept to it and was a model of civility.

Our ability to effectively deal with the pandemic is dependent on many things, not the least of which is civility to one another. Performance to date in many instances has not been reassuring. And the longer COVID remains a factor in our daily lives, requiring unaccustomed behavior, the more civility to one another will be tested.

In the seventeenth century, London, and more broadly British urban culture, was affected by the spread of coffee houses, which were open to all classes, creating a need to understand unwritten rules for “politeness” and “civility.” Books and pamphlets offered advice on how to behave in public and private.

As Ben Wilson notes in his Metropolis: A History of the City, Humankind’s Greatest Invention, “What prevents the human ant-heap from degenerating into violence is civility, the spoken and unspoken codes that govern day-to-day interactions between people. Every moment on any city’s streets is witness to complicated, orchestrated ballet dances of behaviors, as people negotiate shops, streets, offices and mass transit systems.”

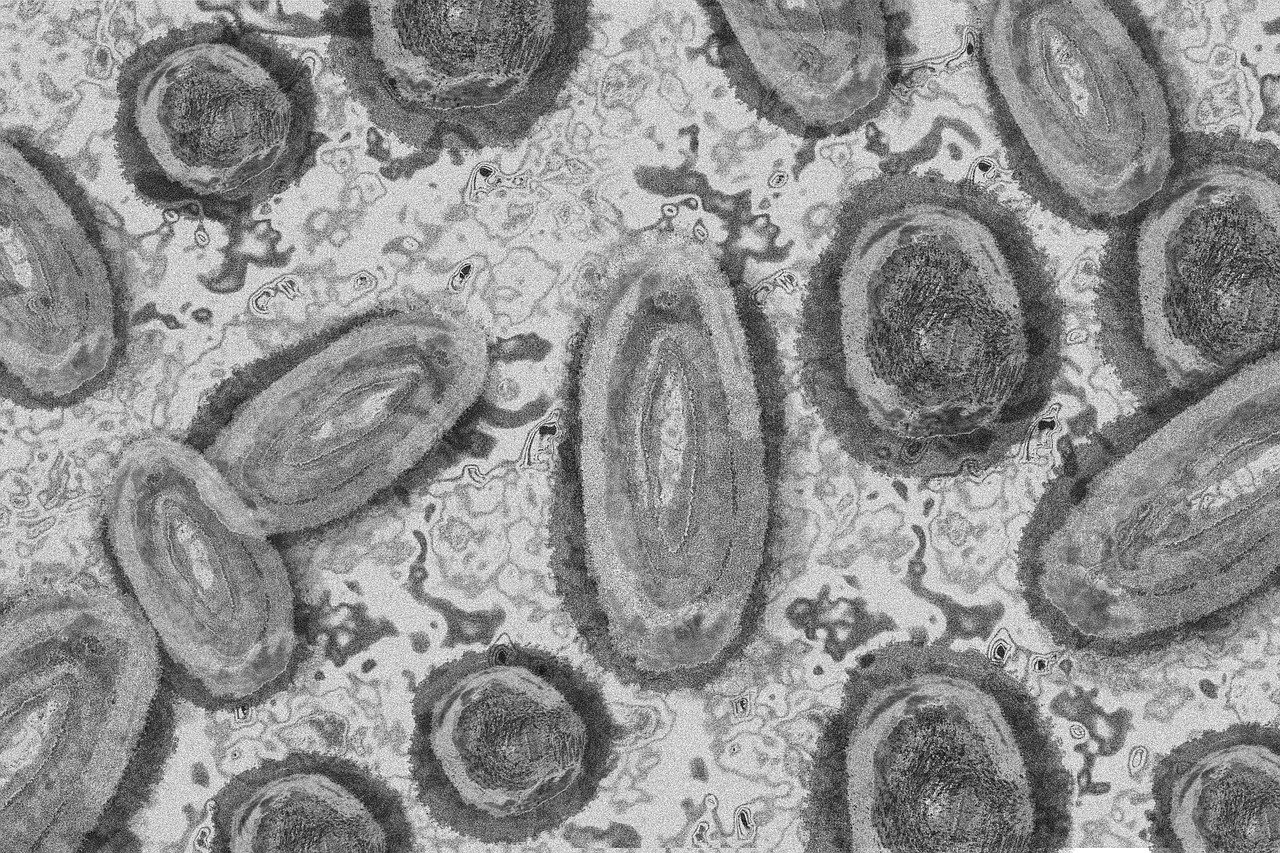

The Impact of COVID on Civility

In a country widely considered a model of civility, thousands in the Netherlands defied a ban on assembling and demonstrated against the Dutch government’s coronavirus lockdown measures on Sunday, January 2, 2022.

Some participants unfurled a banner that read, “Less repression, more care;” another banner said: “It’s not about a virus, it’s about control” on one side and “Freedom.” It was a stark example of civil disobedience linked to COVID with some protestors physically clashing with riot police.

And there have been similar protests all over Europe and elsewhere.

Public protests against a generic restriction are one aspect, but the pandemic has also exacerbated various types of morally uncivil behavior, such as discrimination and hate. It has created opportunities for some political actors to put forward sectarian agendas, grounded in partial interests and controversial beliefs, which breach the demands of justificatory civility.

Furthermore, policies to contain the pandemic have resulted in unreasonable ‘strains of commitment’ for members of marginalized sectors of the population, such as racial minorities, women, the LGBTIQ+ community, and older people.

Sexual relations involving individuals of the same sex also are illegal in most of the Middle-East-North Africa region, although public attitudes toward LGBTQ rights vary according to each country’s socio-economic context and religious doctrines.

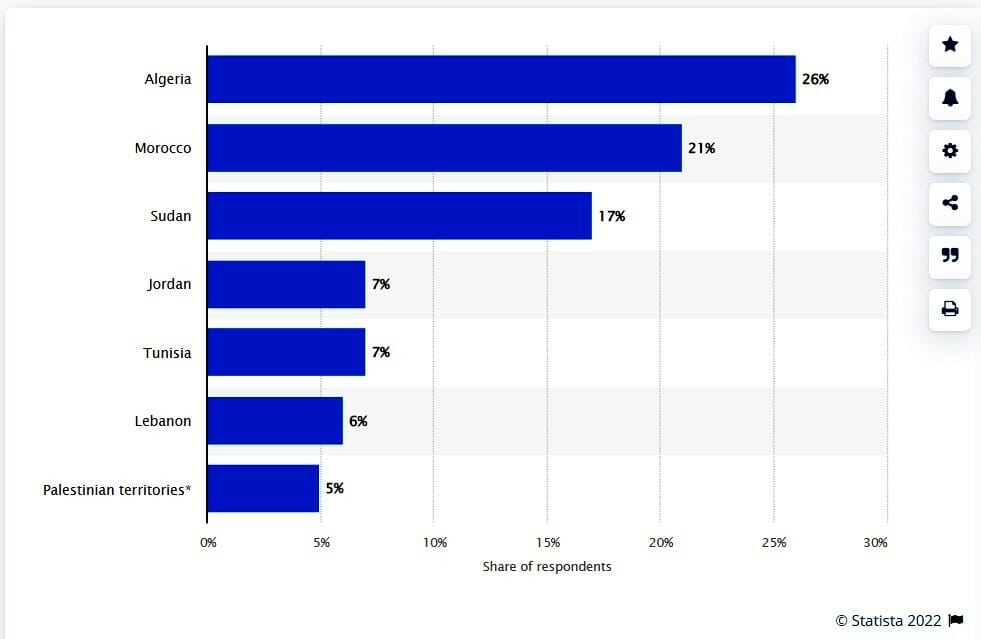

A 2019 study by the Arab Barometer showed that acceptance of homosexuality is low or extremely low across the region:

In Algeria, the 26% of respondents who said being gay was acceptable represented the highest share in the region. The lowest, surprisingly enough, was in the Palestinian territories, Lebanon and Tunisia, even though the latter two had developed over time a reputation for being somewhat more liberal societies in the MENA region.

Although there are signs that attitudes towards Tunisia’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people are improving, activists say police grew emboldened following anti-government protests this year as the country’s economy flailed amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

A study in South Korea provides insight into a modern-day connectivity window on how people behave: “Many people in South Korea are terrified because of reports of large numbers of infected people, which generates social distrust among citizens. This tragic situation chiefly boosts social media users’ anger, hostility, and anxiety toward specific contentious groups or relevant issues (e.g., nationality, race/ethnicity, religion). Some South Koreans aggressively blame local residents who live in China, as well as the Korean policy against the spread of COVID-19.

Appropriate COVID Behavior, Who Listens and Who Makes Them

Public health officials almost everywhere recommend wearing a mask to reduce the spread of COVID-19, yet individual compliance varies.

Understanding the full range of determinants of mask-wearing is critical for promoting evidence-based public health solutions to slow the spread of COVID-19. Using data from a survey of over 3,000 respondents across six U.S. states, a study investigated the relationship between psychological factors, including threat- and efficacy-related perceptions, on mask-wearing behavior.

It is found that perceptions of self-efficacy (e.g., ability to wear a mask) and response efficacy (e.g., the effectiveness of mask-wearing in reducing COVID-19 transmission) better predicted mask-wearing behavior than a number of commonly cited sociodemographic factors. These results suggest that messaging focused on the relative ease and effectiveness of mask-wearing can increase compliance with public health recommendations for mitigating COVID-19.

What More Can Be Done to Improve COVID “Civility”?

If the behavior in the pandemic is a function of mutable group processes rather than fixed tendencies, then behavioral change is possible. Understanding the role of group processes can help design more effective interventions to support collective resilience in the public in the face of the pandemic and other threats.

“Toolbox” tips are available to navigate some of the emotional responses that families experience with COVID-19. These provide general information about common emotional responses of children, teens, and families when one is tested positive or ways for families, parents, caregivers, and educators to better deal with an infection or with legitimate concerns where community infection rates are trending upward.

A final tip for us all – from one of the most revered among America’s founding fathers

The first American President, George Washington when 14 years old in 1745, copied down “The Original 110 Rules of Civility” which had been written by a 16th century Jesuit priest. Some of those civility rules are highly relevant today as we try and deal with our current global health crisis:

- Every action done in company ought to be done with some sign of respect to those that are present

- If you cough, sneeze, sigh, or yawn do it…privately putting your handkerchief or hand before our face and turn aside

- Show not yourself glad at the misfortune of another though he were your enemy

- Labor to keep alive in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called conscience

Washington’s home, Mount Vernon, is owned and maintained by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, a private, non-profit organization, that has put together, inter alia, the full 110 Rules that may be found here.

In 2022 and beyond, we will have to do better in being far more civil to each other than we have so far shown.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists and contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Mount Vernon – To illustrate Rule number one Source: Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association EV-4260/RP-623