Companies including BP, TotalEnergies, and Eni will reap the near-term revenues from liquified natural gas (LNG) projects in Africa. Mozambique, Nigeria, and Senegal are expected to wait until the mid-2030s or 2040s for significant returns, which might not materialize. As the world moves toward clean energy, future LNG demand is uncertain and oversupply is a real risk.

Context

To respond to projected energy demand, since late 2021, European countries began negotiating new LNG-related agreements with several African countries, including Algeria, Nigeria, Mozambique, Senegal, Egypt, Namibia, and South Africa.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has made several tours to Africa over the last 2 years to open talks on gas extraction and LNG production in Senegal and signed LNG production memorandums of understanding in Egypt and Nigeria. Former Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi negotiated gas deals with Algeria, Egypt, Angola, and the Republic of Congo. French President Emmanual Macron has also courted several African countries to help increase gas imports. In parallel, France’s TotalEnergies, the largest fossil fuel company on the African continent and Italy’s partially state-owned Eni, the second largest, hold a majority share in several of the LNG deals that have either been finalized, are awaiting final investment decisions, or are in the feasibility phase.

LNG demand is far from guaranteed, and oversupply is a real risk.

The Business Case for New African LNG Projects Is Not Favourable for Host Countries

Delayed Revenues

As shareholders, both African governments and European companies want prospective LNG projects to be profitable. However, host governments generally place more importance on long-term profitability than companies due to delayed revenue-sharing structures. For example, in Mozambique and Mauritania, LNG deals were designed so that most of the financial return initially flows to the companies while significant government earnings only come later, in the mid-2030s and 2040s. This revenue-sharing structure shifts risk to host countries, as near-term revenues are more predictable than those in the medium- or long-term.

In the event of less favourable market conditions from the mid-2030s, host governments face the risk of generating significantly less revenue than predicted. By the time government revenue shares reach their maximum amid global decarbonization trends, the profitability of these projects may be undermined by a global LNG supply glut, coinciding with the declining EU LNG demand predicted by the IEA and EU Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER), respectively. European governments and politicians are supporting LNG deals that are more likely to benefit European oil and gas companies, while the financial risk is disproportionately taken by African states.

LNG Oversupply

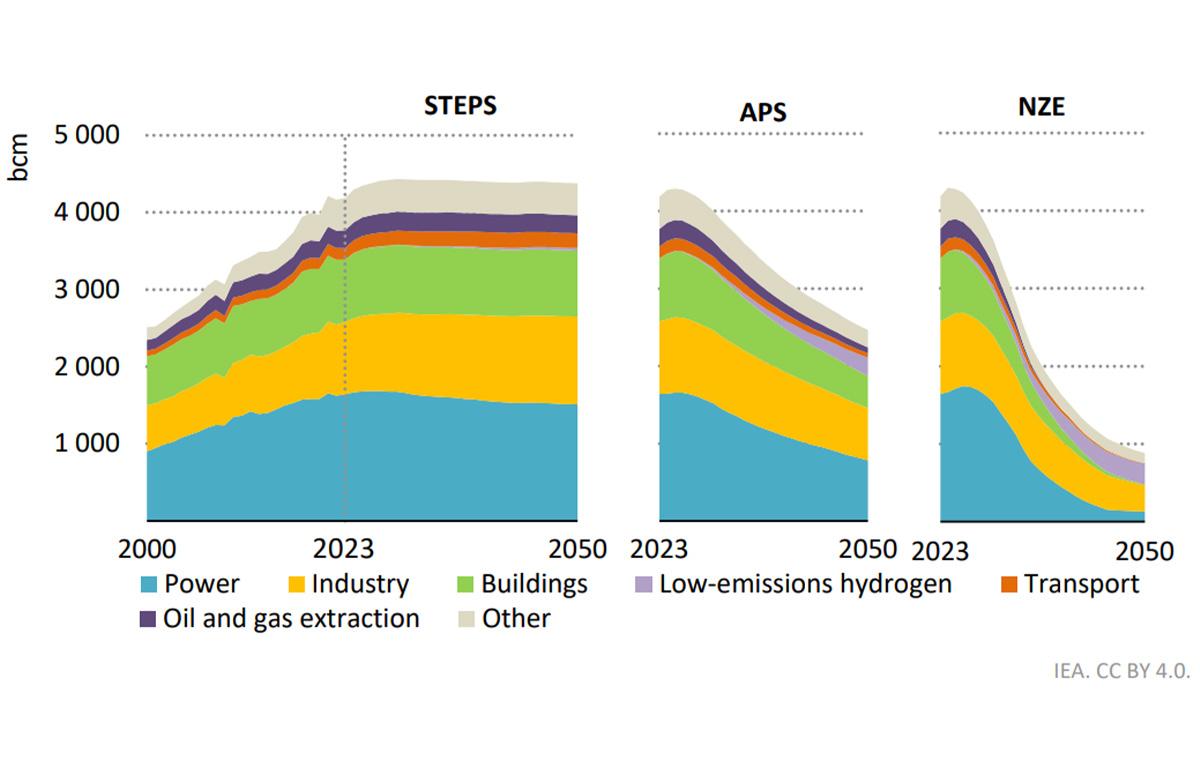

At the global level, the IEA estimates that under all its scenarios, natural gas demand will peak by 2030 and then decline to 2050. Under the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 (NZE) Scenario and the Announced Pledges Scenario (APS), declines are rapid, while under the Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), the decline is slow (Figure 1). In all scenarios, the pipeline gas trade will decrease from 2030. LNG trade also decreases from 2030 in the NZE Scenario and APS, and even in the STEPS, where LNG trade increases from 2030, it is still less than committed LNG export capacity expansion. Global LNG Hub estimates this increase in global LNG capacity to be 40% by 2030.

As a result, in all the IEA scenarios, there is a surplus of LNG export capacity to 2040 relative to LNG trade requirements, leading to an LNG supply glut.

Figure 1. Global natural gas demand by IEA scenario, 2000–2050

The EU has approved and launched legislation to cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030. This “Fit for 55” package was complemented by the REPowerEU plan to enhance renewable energy and energy efficiency in response to the energy crisis spurred by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. According to ACER, “Europe’s Fit for 55 legislative package envisages a decrease in EU gas demand of 30% by 2030, relative to 2019 levels.”

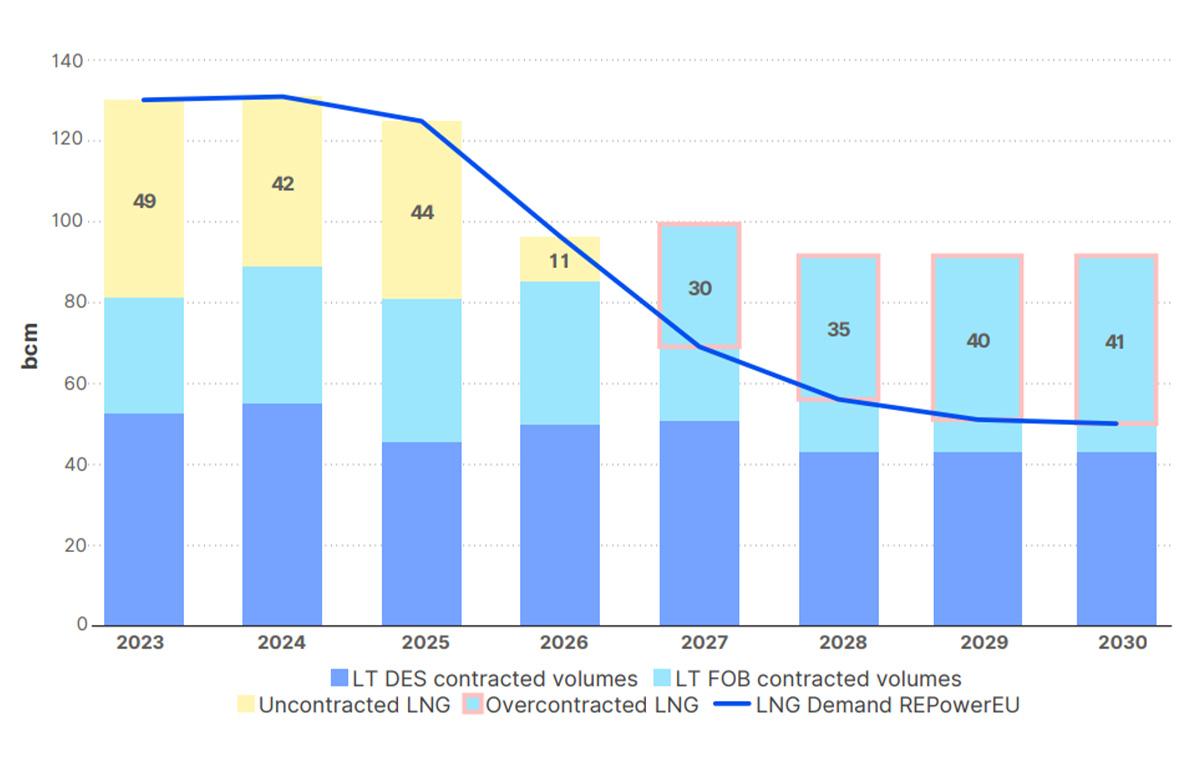

Figure 2. Falling LNG demand in the EU under the REPowerEU scenario

The REPowerEU scenario in Figure 2 highlights the EU’s reliance on the LNG spot market, with the EU depending on slightly over 40 cm of LNG spot supply from 2024 to 2025. However, by 2026, the gap in uncontracted LNG shrinks to just 11 bcm. Notably, between 2027 and 2030, the situation shifts entirely: long-term EU contracts for LNG would surpass projected demand. As a result, the EU’s exposure to spot LNG would be minimal, limited to balancing and scheduling. The EU is expected to be over-contracted by 30 to 40 bcm during this period, with the surplus likely being redirected to global LNG markets, aided by flexible FOB contractual terms.

Increasing Competition

If LNG supply outpaces demand, there will be increasing competition between producers. In our assessment, African producers are more vulnerable to price competition than other global producers because they have higher breakeven prices for LNG exports. This is based on a calculation of asset-level breakeven gas prices, weighted based on their total forecasted production volumes according to the Rystad UCube data. African producers Algeria, Senegal, Nigeria, and Mozambique have higher LNG breakeven costs when compared to the largest producers and key competitor countries such as the United States and Qatar (Figure 3). While Algeria is also an African country, it has been exporting LNG since well before the other three countries, with Sonatrach, its national energy company, holding majority shares in all the LNG plants.

Regional variations between breakeven costs can be attributed to technical, financial, and security factors, such as the cost of capital, taxes, and royalties. For instance, in Mozambique, the security challenges in Cabo Delgado (where LNG projects are located) could escalate costs, threaten production, and reduce revenue for the government.

Stranded Assets

“Stranded assets” are defined as “assets that become devalued before the end of their economic life or can no longer be monetised due to changes in policy and regulatory frameworks, market forces, societal or environmental conditions, disruptive innovation, or security issues.”

Higher breakeven gas prices make national production more vulnerable to global market fluctuations, as it would become unprofitable if global gas prices fall below domestic breakeven levels. These higher prices indicate increased production costs and reduced profit margins. With a forecasted LNG supply glut until at least 2040 and intensified market competition, new entrants like African producers with high operational costs are at greater risk of failure, potentially leading to the shutdown of operations and the creation of stranded assets. The majority of LNG deals between fossil fuel companies and African states, with the exception of existing projects in Algeria, have granted higher shareholding percentages to foreign fossil fuel companies (Offshore Technology, 2023; Energy Capital & Power, 2024; Global Energy Monitor wiki, 2024; Lusa, 2023; Global Fossil Infrastructure Tracker, 2022; BP, 2023).

LNG projects still under development in Mozambique, Senegal, and Nigeria are at high risk of becoming unprofitable, especially if they have high production costs or are exposed to fluctuating LNG export prices. New projects face even greater risks, as development typically takes 5 to 10 years; they are unlikely to begin producing—let alone delivering government revenues—before the 2030s, when global demand could be much lower. Even where there are prospects to utilize new gas reserves for domestic energy, this requires substantial infrastructure investments, including regasification plants and distribution pipelines.

The EU’s decarbonization goals under the RePower EU and Fit for 55 packages create a mismatch between EU LNG demand and the planned LNG infrastructure in Africa. Furthermore, supporting development and procuring additional LNG from African countries whose LNG production costs are relatively high (Figure 3) places a burden on African countries to maintain such assets over the long term, risking stranded assets.

Stranded asset risk is high for these countries because European demand may drop before much of the current LNG project pipeline can be developed. Supporters of LNG projects suggest that African countries can pivot away from Europe and instead supply increasing gas demand that could appear in Asia. However, the IEA scenarios show a global decline in natural gas demand (Figure 1), coupled with LNG oversupply.

Related Articles: Why Canadian Liquefied Natural Gas Is Not the Answer for the Europe’s Short-Term Energy Needs | Germany, France and Italy Respond to Gas Crisis: More Coal, More Oil, New Suppliers | Europe to Ration Gas as Russia Limits Supplies Further

Host Countries Risk Falling Into a Debt Trap

The push by European governments and companies to expand oil and gas exploration and LNG terminals in Africa creates a promise for a new revenue stream that, if not properly planned for by host countries, could lock them into debt driven by long-term fossil fuel revenue expectations and impeding their shift to renewable energy. Even though LNG projects are majority-owned by private companies, governments typically acquire a debt-funded minority equity stake in the project. For example, in Nigeria, Shell, Total, and Eni own a total of 51% of Nigeria LNG; the remaining 49% is owned and financed by the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited, a state-owned company.

According to Carbon Tracker, oil and gas revenues form a crucial financial base for seven African nations—Algeria, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, Gabon, Republic of Congo, Angola, and Chad—with these countries relying on oil or gas for between 62% and 98% of their government income. Additionally, more than half of Africa’s oil and gas-producing countries derive over 50% of their total export revenues from oil and gas exports, underscoring the sector’s critical role in their economies.

Fossil fuel companies that have entered into deals with African states, including TotalEnergies, Eni, and BP, hold majority stakes in many of the proposed projects (Figure 4) and, as majority shareholders, will have control of LNG projects over the course of their commercial lives. To attract such investments, African governments often concede lower royalties, profit shares, and ownership stakes and may accept unfavourable terms, like reduced corporate tax revenue. This practice leads to the mortgaging of future fossil fuel revenues for capital, deepening debt through loans from Global North-controlled development banks, such as the IMF or World Bank or, increasingly, from Chinese national oil companies. This situation is particularly concerning given that these African countries have minimal responsibility for climate change and limited capacity to finance their energy transition.

LNG remains costly when accounting for the entire value chain, requiring significant upfront investment in upstream production, liquefaction capacity, specialized storage facilities, and vessels. To pay off these investments, African countries could be getting locked into developments that will leave assets that may become increasingly expensive to maintain, debt that is hard to service and a prospect of revenue generation that is neither stable long-term nor aligned with evolving global energy commitments.

Europe Influences LNG Investments in Africa

Europe’s position on African LNG was precipitated by the crisis following the war in Ukraine. The short-term scramble for LNG to replace Russian imports has led to a shift in the medium-term LNG supply. This led to the high-profile political visits and deals signed with European leaders described above, but the fallout from this was not limited to Africa. Supply concerns led countries such as the United Kingdom, Norway, the United States, and Australia to issue a raft of new oil and gas licences. In particular, prior to the recent change of government, the United Kingdom reportedly planned to issue 72 new licences in 2024, which could lead to 101 million tonnes of emissions, the highest in 50 years.

In addition, European financial markets have further supported LNG developments. Since the signing of the Paris Agreement, about EUR 1 trillion has been raised for fossil fuel investments, with EUR 776 billion (77%) involving a European financial institution.

European Companies Drive Fossil Fuel Developments

European companies like TotalEnergies, Eni, and BP are major investors in LNG export projects in Mozambique, Nigeria, and Senegal. While European governments don’t directly control these companies, they shape the regulatory and fiscal policies that influence corporate behaviour, creating a favourable environment for continued LNG development. Additionally, European governments play a significant role in clean energy investment through initiatives like the Just Energy Transition Partnership. Nigeria and Senegal have included natural gas in their Just Energy Transition Partnership plans with the support of European partners. However, these plans lack clarity on domestic gas infrastructure, which risks undermining broader climate commitments despite efforts to boost domestic electrification.

Fossil fuel companies in Europe have been actively attempting to influence politicians and policy-makers to secure favourable conditions for themselves and their interests.

The Result

Europe’s continued support for LNG developments places African countries at a further disadvantage in their objectives to meet decarbonization goals by the 2050s. Emissions linked to the extraction, processing, and transportation of LNG contribute toward total emissions for the host country, making decarbonization more challenging to achieve.

- Europe should avoid further locking Africa into developments that lead to stranded assets. While African countries can carefully assess the risks associated with high LNG production costs and potential stranded assets, European governments and companies should also show their commitment to a sustainable future by ending support for expansion of gas exploration interests in Africa. LNG deals that seek to extract the natural resources and profits, leaving behind assets that are burdensome to maintain or less profitable, have no place in a sustainable energy system. European involvement in LNG projects should take into account the economic viability of LNG projects under different market scenarios, especially considering forecasted supply gluts in the mid-2030s.

- European companies and policy-makers should avoid measures that risk locking African states into a fossil fuel debt trap. European collaboration should focus on fostering partnerships that benefit both sides, reducing the drive for new fossil fuel extraction and supporting the decarbonization of the energy sector. European companies should reassess the long-term viability of LNG projects, given the predicted global supply glut and declining demand, and consider investments aligned with the sustainable energy supply chain instead. Such companies, with the support of policy-makers, should support developments that seek to diversify the host country’s energy sector, supporting infrastructure investments for domestic energy development to minimize creating a debt trap cycle emanating from fossil fuel dependence.

- A push for gas by Europe in Africa undermines solidarity in meeting the emissions reduction targets. Europe should reduce its political and commercial support for LNG infrastructure in Africa and prioritize renewable energy investments to avoid “fossil fuel lock-in” and help African countries meet their decarbonization targets. European companies and financial institutions play a key role in African LNG exploration, so this is partly a European problem. European governments must introduce stricter regulations to curb corporate lobbying by fossil fuel companies, ensuring that climate policies and commercial agreements align with a phase-out of fossil fuel support and focus on renewable energy development both domestically and internationally.

** **

This article was originally published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and is republished here as part of an editorial collaboration with the IISD.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com