Rivers are more than water that flows across the landscape. Two billion people rely directly on rivers for drinking water, and 25 percent of the world’s food is produced via river irrigation.

Unfortunately, rivers worldwide are being damaged. They are contaminated with agricultural fertilizers, industrial waste, and plastic, causing pollution. Moreover, river water is extracted at an unsustainable pace, degrading river ecosystems and impacting biodiversity. Additionally, rivers have been buried underground for centuries, straightened into concrete canals, and dammed.

The more we abuse our rivers, the less access we have to clean water, and the less rivers can help us fight the impacts of climate change, such as droughts. Giving less space to waterways increases the risk of damaging floods and reduces water infiltration to feed groundwater reserves.

These challenges are not unique to one country or one continent. River pollution occurs everywhere, and the effects of climate change in Europe can be very similar to those in Africa.

The way we try to protect rivers today strongly varies between countries. The most important question from an SDG6 perspective is: how do we safeguard rivers sustainably and equitably?

To get more insights into this question, looking at what others have done is useful. The international NGO Join For Water set out to do that in their Twin River initiative. As twin cities exist, a ‘twin river link’ has been established between the Mpanga River catchment in Uganda and the Getes River catchment in Belgium. Within this initiative, the exchange of knowledge and experiences on protecting and conserving rivers was central.

RELATED ARTICLES: Water Stewardship: The Guiding Light to Sustainable Development | Most Companies Unprepared for New ESG Rules, Report Finds | Health Flows From Safe Water

What does the law state?

Rivers are part of wider river catchments. Therefore, the entire catchment must be considered when protecting a river. Only through a holistic approach, multiple sources of pollution within a watershed can be addressed, such as urban and agricultural pollution runoff, landscape modification, depleted or contaminated groundwater, and the introduction of exotic species.

In both the river catchment in Uganda and Belgium, river catchment management plans have been drawn up and embedded in local legislation.

One component that comes back in both plans is the need to protect riparian zones, which are the areas that connect the river to the land. To this end, maintaining buffer zones along rivers is a common conservation method.

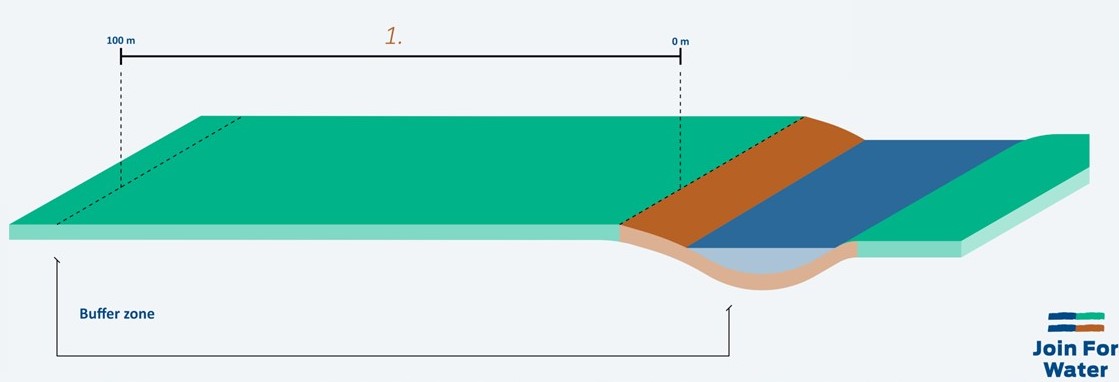

Uganda has clear legislation around buffer zones for freshwater ecosystems. A 100-metre buffer zone must be respected around rivers and wetlands, where, in principle, no (agricultural) activities are allowed. The wetlands themselves are completely off-limits.

However, in practice, these zones are often used for agricultural activities, and enforcement still needs to be improved, leading to severe degradation of rivers and their ecosystems.

There must be functioning mechanisms to bring together the right stakeholders and effectively address population and land pressure challenges in the buffer zones.

There need to be more institutional linkages (e.g. for law enforcement), more sustainable compensation mechanisms for the loss of land when moving out of the buffer zones, and mediation and law enforcement efforts for solving persisting conflicts of interest (gravel mining, etc.

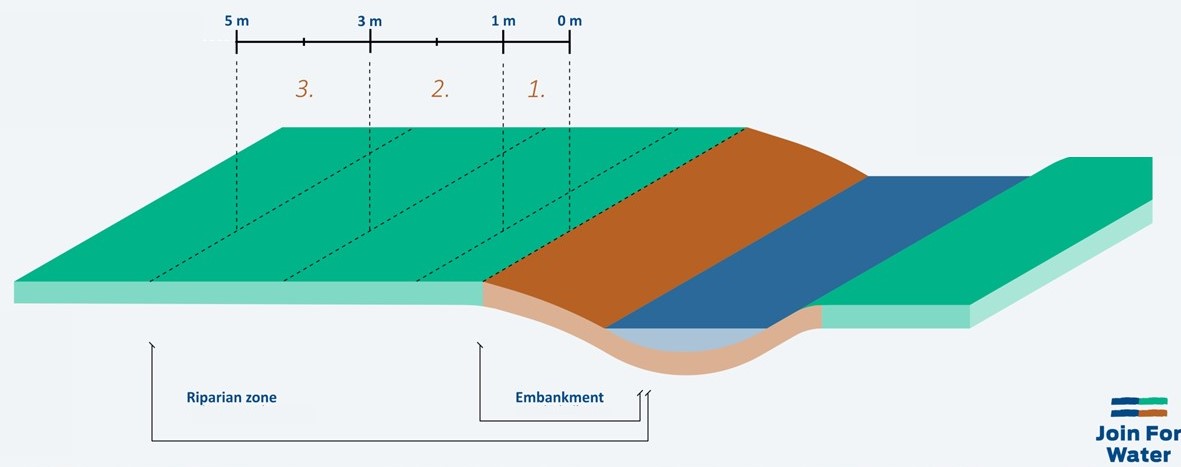

A legislative framework for buffer zones also exists in Belgium but needs to be more ambitious. Pesticides and tillage are prohibited in a strip of one meter from the upper edge of the embankment, and no crop protection products are allowed within the three-meter zone. Fertilizers and new structures may not be erected within a strip of five meters from the upper edge of the embankment, although there are exceptions.

Different state-supported mechanisms exist for farmers and landowners to claim compensation for protecting the buffer zones, but there needs to be clear enforcement, and initiatives are often voluntary. This situation leads to scattered actions that contribute only partially to the protection of rivers at the catchment scale.

Towards achieving SDG6

Both examples show that more than the legal protection of buffer zones is needed to protect freshwater ecosystems such as rivers. The scale and context show major differences between the two river catchments in Uganda and Belgium.

Yet, the Mpanga and Getes river catchments share the same key challenges related to translating policy into realistic protection practices that can be upscaled across entire river catchments.

Across the world, many different approaches to river protection have been implemented. It can either be organized voluntarily or rather restrictive. A restrictive policy excludes certain areas from any activities (like in Uganda). A voluntary approach is the opposite and starts from commitments made by landowners. A restrictive system requires control, and a voluntary process often requires high commitment. A middle way is usually found in working with incentives, where users or owners are encouraged to take or follow certain measures (like in Belgium).

Either way, from an SDG 6 perspective, the restrictive approach could be more realistic and desirable. It is important to find mechanisms to sustainably protect rivers without completely restricting access to the benefits these ecosystems provide to people.

Developing such tools should involve as many stakeholders as possible to ensure that a broad group supports and owns key decisions, integrating environmental goals with economic, social, and cultural objectives.

If we manage to do that, no one and no river will be left behind, and SDG6 can be achieved.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Mpanga River. Featured Photo Credit: Joseph Muhumuza via Join For Water