The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, or Pacific trash vortex, is a collection of marine debris spanning from the North American West Coast to Japan. It’s made up of two patches: the Western Garbage Patch near Japan, and the Eastern one between Hawaii and California.

We recently described how the garbage patch came about and continues to expand in size and scope, highlighting the finding that new neopelagic communities — composed of coastal and pelagic species that normally live thousands of kilometers away — are forming and thriving on it.

This Garbage Patch and others are gaining increased scientific and media attention, by international and national bodies, NGOs, and academics, each with their own perspective.

Here we are bringing a different focus: One Health, a multidimensional concept that takes into account animal, human, plant, and environmental interactions and impact.

That said, what will not be dealt with in any depth are the direct and indirect economic and health effects, which are clearly substantial in many instances, but more appropriately addressed in another article.

Animals and Plants Effects

Animals, over 700 species including seabirds, fish, turtles, and marine mammals, mistakenly eat plastic and other debris instead of real food (or accidentally, when the plastic is attached to their food).

Turtles, for example, often mistake plastic bags for jellyfish. The plastic can take up room in the turtles’ stomachs, making them feel full and stopping them from eating real food.

Ingestion of plastic by animals can and often does result in death via loss of nutrition and starvation, internal injury or intestinal blockage. At the same time, abandoned fishing lines, nets and equipment can ensnare and drown dolphins, porpoises and whales, among other animals.

One way or another, plastic pollution kills over one million seabirds and 100,000 marine mammals every year.

Looking beyond this data, how exactly plastic ingestion affects animals, especially in the long run, remains a pressing question in the field; as conservation biologist Matthew Savoca explains, plastic ingestion can harm wildlife without causing death.

The “subtler, sublethal effects…could be much farther-reaching,” Savoca writes.

Some of the chronic effects that plastic ingestion has been found to have on invertebrates, mammals, birds and fish — effects that have the potential to impact the entire population of a species — include changes in behavior, loss of body weight and condition, reduced feeding rates, decreased ability to produce offspring, chemical imbalances in organisms’ bodies and changes in gene expression.

Seabirds were the first sentinels of possible risks to marine life from plastics: A 1969 study, published decades before the Great Pacific Garbage Patch was discovered, examined young Laysan albatrosses (Phoebastria immutabilis) that had died in Hawaii and found plastic in their stomachs. So, it is fitting that the first disease attributed specifically to marine plastic debris, “Plasticosis,” was also described in a seabird.

“This study,” co-author of the research that helped coin the term “Plasticosis” Dr Alex Bond said, “is the first time that stomach tissue has been investigated in this way and shows that plastic consumption can cause serious damage to these birds’ digestive system.”

Scientists have recently also observed associations between plastic ingestion and pathogenic illness in fish, with a 2022 study showing that microplastics exacerbate virus-mediated mortality in fish.

As the study’s authors explain, “[m]ortality increased significantly when fish were co-exposed to virus and microplastics, particularly microfibers, compared to virus alone.”

“This presents the unique finding that microplastics may have a significant impact on population health when presented with another stressor,” the researchers conclude.

Plasticosis may help explain how pathogens find their way into the body via a lacerated digestive tract.

What plastics do to humans

Unsurprisingly, the potential dangers of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch extend to humans; as Director General of WWF Marco Lambertini put it: “Not only are plastics polluting our oceans and waterways and killing marine life – it’s in all of us and we can’t escape consuming plastics.”

By now, microplastics have been discovered in human blood, stool, and breast milk as well as in our lungs, livers, spleens, kidneys — even in the placentas of newborn babies.

They’ve also been found in the stomachs of nearly half of the most important species for global fisheries.

Apart from ingesting microplastics by eating animals that had previously eaten them, like fish, studies show that humans are also ingesting them through the consumption of salt, beer, honey, and sugar.

In 2019, a WWF-commissioned study on how much plastic humans ingest, carried out by the Australian University of Newcastle, found that we ingest about 2,000 pieces of microplastics — the equivalent of one credit card — per week.

The single largest source of ingestion, the study shows, is through water, both bottled and from the tap. In fact, most likely as a result of packaging and processing, higher amounts of microplastics were discovered in bottled than in tap water.

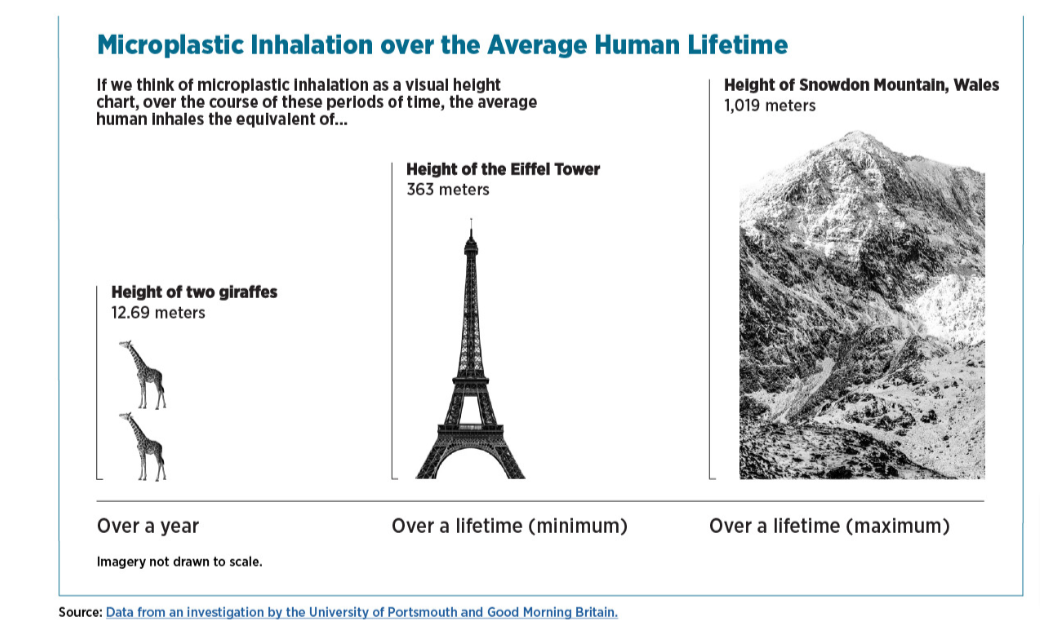

What’s worse, we may not be able to breathe without inhaling plastic either; as recent studies show, microplastic particles are “constantly lofted into the atmosphere,” their inhalation being another key pathway into human bodies.

According to a 2019 study on the human consumption of microplastics, we can inhale up to 22,000,000 micro and nanoplastics per year.

While the immediate medical risks are negligible, Associate Professor of Medicine and Health Sciences Sarva Mangala Praveena explains that scientists are increasingly concerned about the long-term effects of microplastics on human health.

While the immediate medical risks are negligible, Associate Professor of Medicine and Health Sciences Sarva Mangala Praveena explains that scientists are increasingly concerned about the long-term effects of microplastics on human health.

“Key to this concern are the chemicals used in the manufacture of plastics, some of which have already been linked to serious diseases,” Praveena writes.

Impacts on the environment and climate

Plastic pollution can also disrupt marine ecosystems by helping to move species from one place to another.

Algae, barnacles and crabs, for instance, can attach themselves to marine debris and be carried across the ocean. An invasive species can settle and establish in a new environment, threatening biodiversity with its potential to outcompete or overcrowd native species.

Beyond the risks for the marine environment, recent studies have suggested that microplastics and nanoplastics can travel long distances through the air and, alarmingly, affect the formation of clouds.

Traveling by air, microplastics were found to have reached regions as remote as the Arctic, “where they may contribute to accelerated warming through absorbing light and decreasing the surface albedo of snow,” according to the OECD.

“The people who invented plastics all those decades ago…” Atmospheric Scientist at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand Laura Revell said, “I doubt they envisaged that plastics were going to end up floating around in the atmosphere and potentially influencing the global climate system.”

“We are still learning what the impacts are for humans, ecosystems, and climate. But certainly, from what we know so far, it doesn’t look good,” Revell added.

Related Articles: Plastic Waste Is Creating New Communities on the Ocean’s Surface | Turning Ocean Garbage Into Green Fuel | Scientists Find Microbes That Can Break Down Plastic in the Cold

It’s also important to remember that plastics originate as fossil fuels and that they emit greenhouse gases throughout their lifecycle, from extraction and transport to refining and manufcaturing to waste management.

“Greenhouse gas emissions from the plastic lifecycle threaten the ability of the global community to keep global temperature rise below 1.5°C. By 2050, the greenhouse gas emissions from plastic could reach over 56 gigatons — 10-13% of the entire remaining carbon budget,” asserts the “Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet” report, published in 2019 by the (non-profit) Center for International Environmental Law.

At the time of writing, the production of plastic alone accounts for 3.4% of global greenhouse emissions while about 4-8% of the global oil consumption is associated with plastic.

If the world continues to produce plastic under a business-as-usual scenario, the World Economic Forum estimates that plastic could account for 20% of the global oil consumption by 2050 and that its production will double over the next two decades.

As WWF Director-General Marco Lambertini said ahead of the UN plastic pollution treaty talks in Paris (May 29-June 2):

“On our current trajectory, by 2040 global plastic production will double, plastic leakage into our oceans will triple and the total volume of plastic pollution in our oceans will quadruple. We cannot allow this to happen.”

What is and/or can be done

In 2022, United Nations member nations voted to negotiate a global treaty to end plastic pollution, with a target completion date of 2024. This would be the first binding agreement to address plastic pollution in a concerted and coordinated manner.

As a series of WWF-commissioned technical reports shows, global plastic bans, phase-outs and control measures are “entirely feasible.”

The reports, released on May 15, identify the most damaging plastic products and propose measures to “eliminate, reduce or safely manage and circulate these plastics.”

Among the proposed measures is a global ban and phase-out of the “most high-risk and unnecessary” single-use plastic items, including, inter alia, plastic cutlery, vapes, and microplastics in cosmetics.

These measures could be included in the plastic pollution treaty text, which is set to be published ahead of the December 2023 talks.

But dealing with future limitations on plastics, and only addressing this aspect, is not enough.

This is a problem that affects everything in the ocean and above, in the air, impacting animals, plants and humans. Therefore a more holistic approach will be needed to effectively tackle the continuing harm to animals, humans and plant life.

In short, what is needed is the One Health approach. This requires cross-sectoral collaboration between human and veterinary health experts, oceanographers, agricultural specialists, and private sector interests.

Recently four key UN agencies, WHO, FAO, WOAH, and UNEP, agreed on an operational definition of One Health and joined together for a “Call to Action.” If these technical organizations effectively collaborated in devising a strategy for containing the harmful fallout from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch it would be a major triumph. Success here could be far-reaching, including establishing a broader Law of the Sea.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: A 1 liter mason jar holds the plastic debris collected over approximately 3 hours from surface trawls, conceptualizing the unimaginable number of plastic fragments and particles swirling in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Featured Photo Credit: Greenpeace.