Henry David Thoreau, best known for penning Walden and Civil Disobedience, spent two years at Walden Pond, a reclusive lake, in order to seek a happier way of living.

Thoreau eventually returned to work at his father’s pencil factory. Here he researched German pencil making techniques to launch the family brand into being known as “America’s best pencils”. This perhaps, was an early echo of his literary talents and suitability to writing.

It was around this time that Thoreau decided to return to teaching. In his mind, it must not have been evident that other and greater possibilities were available to him, for when his second attempt failed a short while later, he returned to the pencil company.

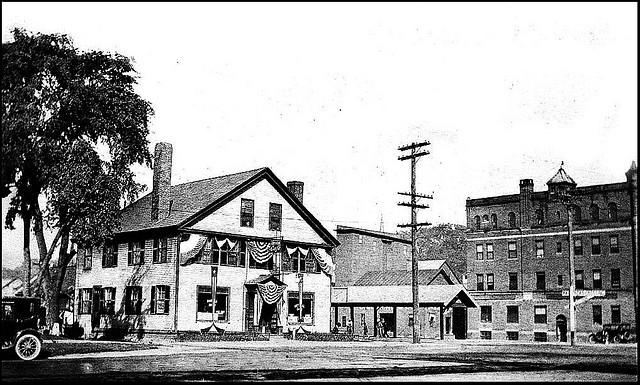

Image taken from: The Keene Public Library, a photo of Thoreau’s childhood home “Dunbar House” – Dunbar House, Keene NH.

At the same time, the fledgling author’s growing sense of independence was contradicted by his living situation in his family home. Consistently busy and noisy, the Thoreau family home was no longer a suitable place for young Henry, who had previously tried so hard to follow in the paths already paved by his family.

![Image taken from page 5 of '[Walden; or Life in the Woods.]'](https://i.embed.ly/1/display/resize?key=1e6a1a1efdb011df84894040444cdc60&url=%2F%2Ffarm4.static.flickr.com%2F3770%2F11285387234_d4d38e9c09_z.jpg&width=810)

On July 4th of 1845, almost as a wry nod to American independence, Henry David Thoreau began to live in a small shack that he had assembled himself on the shores of Walden Pond, near his home in Concord, Massachusetts. At Walden Pond, Thoreau experimented with living off of the land, and reversing the tradition at the time of working for six days of a week and resting for one, by working for one day and finding outlets for his transcendentalist beliefs during the other six.

During this time, Thoreau created his most famous work Walden, a musing on how man can truly live in harmony with nature, and shortly after leaving Walden Pond, penned Civil Disobedience as a response to a short stint in jail, after refusing to pay his poll taxes. Civil Disobedience, alternatively, discussed the vices of man when in an organization.

In Walden, Thoreau compares living in relative isolation to “a draught of morning air,” medication for the soul. He speaks fondly of the happenings around the pond; mostly small events like the growth of tender spring plants, his gruffly charming neighbor, and how he always leaves three chairs out for company. Thoreau’s recount of his time at Walden Pond is movingly beautiful, but also an honest look into his positive experiences with isolation. As Thoreau exchanged his human company for the woods and waters around him, he also found that he was satiated with the company of his thoughts and his land.

Thoreau’s satisfaction in being alone and occupied by nature is something uncommon and difficult to find today. Depature from constant contact is an act closer to death than independence, and few pieces of land remain for us to create our own Walden Ponds. But Thoreau’s ability to find so much happiness just by keeping himself busy with his daily tasks and his observations of the world around him is something admirable and freshly different than the modern norm.

Likewise, though Thoreau advocated for an extreme departure from society, his life narrative is a good example of how to live ‘independently’ and moderately in the modern world. Thoreau tried to follow in the footsteps of his siblings when he took up teaching, but let his personality lead him away from that, despite returning to it twice. Thoreau also spent significant time at his family’s pencil factory, but found no joy in that either. His back and forth struggle in his early life is almost an exact echo of what is experienced by young professors and college graduates today– a tentative few steps here, a few steps there, but a fear of going into the unfamiliar. Likewise, the influence of family and traditional career paths enjoyed in the family play just as strong an influence on us, as they did on Thoreau.

Henry David Thoreau may ultimately be a wonderfully simple example of how to navigate unhappiness and uncertainty in what one does, as when he found his true calling, he succeeded far beyond his ability to create “America’s Best Pencils”.

As Thoreau urges at the end of Walden, “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.”