The iron-based meteorite – said to be 4.5 billion years old – was found near the Somalian town of El Ali by prospectors of a small mining company.

The reddish boulder was unearthed in 2020, though local camel herders have been aware of it for generations, using it as an anvil to sharpen knives and including accounts of it in their music and folklore.

At an impressive 15 tonnes, with a two-metre width, the meteorite is the ninth largest ever recorded. But it was from a mere 70-gram slice, sent to the University of Alberta for analysis, that the two extraterrestrial minerals were identified.

Professor Chris Herd, who teaches at the University of Alberta’s department of earth and atmospheric sciences and curates the meteorite collection, noticed the ‘unusual’ minerals while classifying the meteorite sample.

“What happened was during the process of classifying it, when I was looking at the slides that we had on an electron microscope, I saw some minerals that it couldn’t really identify”, he said.

Herd asked Andrew Lockock, head of the university’s electron microprobe lab, to examine the samples, and Lockock was able to confirm within a day that it contained two new minerals.

This was confirmed by comparing them to minerals that had been created synthetically in France in the 1980s. The two minerals have been named elaliite, after the Somali site where the meteorite was found, and elkinstantonite, after Lindy Elkins-Tanton.

Herd chose the name in order to honour Elkins-Tanton’s work: “Lindy has done a lot of work on how the cores of planets form, how these iron-nickel cores form, and the closest analogue we have are iron meteorites. So it made sense to name a mineral after her and recognise her contributions to science,” he said.

Herd explains that studying the mineral composition of meteorites is “armchair solar system exploration, in a lot of ways. (…) We’re trying to constrain the variety of conditions that have existed within different planetary bodies.”

These findings cannot just offer insight into asteroid formation, but may also translate into as yet unknown tangible uses for humans: “whenever there’s a new material that’s known, material scientists are interested too because of the potential uses in a wide range of things in society,” says Herd.

The sample analysed by the team in Alberta was a tiny fraction of the meteorite, and it is possible that more unknown minerals could be found in the rest of the rock. However, whether the researchers will be able to further explore the rock is uncertain. Herd says there are reports that it has been moved to China in order to be sold.

Abdul Abiikar Hussein, a geologist at Almass University in Mogadishu who examined the meteorite when it was first unearthed, has expressed worry that the rock will be cut up into smaller pieces for sale, thus destroying an invaluable piece of Somali cultural and national heritage.

He calls for the Somalian government to “awake from their sleep and return it back to Somalia.”.

Given the current political situation in Somalia – a country in dire need of humanitarian aid as it has suffered from a deadly combination of decades-long internal conflicts and recurring drought – it is unlikely that his call will be heard.

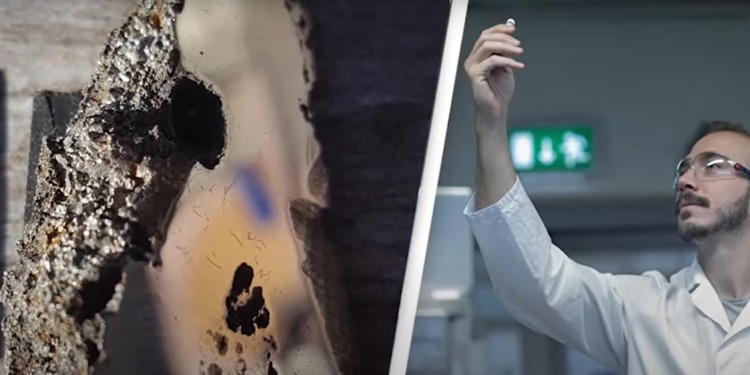

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: El Ali meteorite (left) and University of Alberta material scientist (right) Source: screenshot from Oneindianews video