Editor’s Note: We’re happy to publish this article from the Institute of Economics and Peace (IEP), one of our partner organizations, particularly as it comes at a time of renewed concern over terrorist attacks of the kind recently suffered in Israel, with five bystanders killed by a Palestinian gunman in a suburb of Tel Aviv. The author, Isaac Kefir, a graduate from the London School of Economics and a Research Fellow at IEP who has previously taught at Tokyo University and Syracuse University, shows that the roots of global terrorism are far more complex than usually thought and now extend to a new area: the Sahel.

The Sydney-based think tank, the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) recently released the ninth edition of the Global Terrorism Index (GTI). Based on data-driven evidence-based analysis, the new GTI report reveals a shift in the dynamics of terrorism, which has become more concentrated as activities have moved from North to South, the Sahel being a case in point.

The #Sahel has become increasingly more violent over the past 15 years, with deaths rising by over 1000% between 2007 and 2021. pic.twitter.com/baYUA6UMpW

— IEP Global Peace Index (@GlobPeaceIndex) April 7, 2022

Firstly, and this may come as a surprise to many, the data shows that deaths from terrorism have continued to fall since their peak in 2015: In 2021, there were 7,142 deaths from terrorism, a third of what they were in 2015. The data also reveals that the lethality of attacks has decreased from 1.6 deaths per attack to 1.4 deaths per attack over the 12 months analysed.

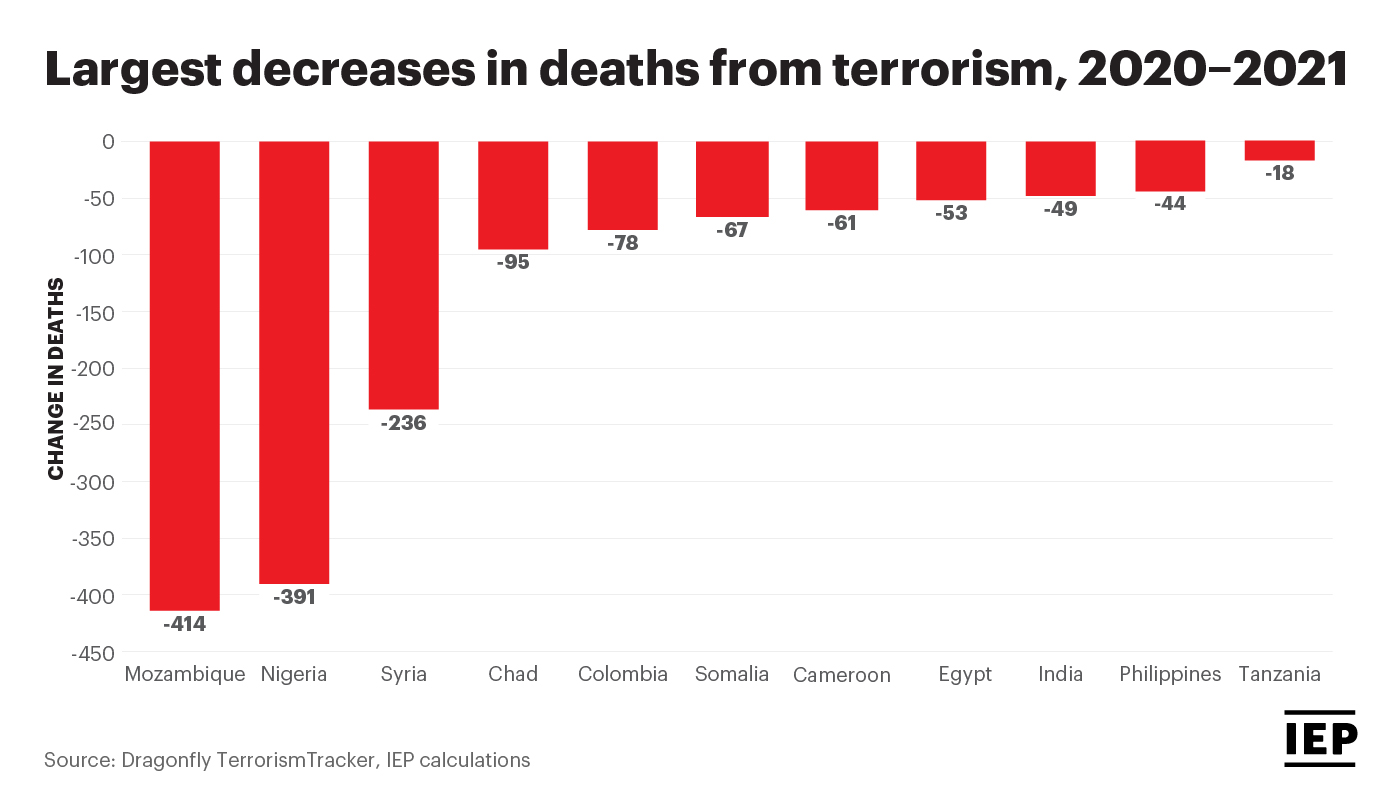

Secondly, the fall in deaths was mirrored by a reduction in the impact of terrorism, defined as the numbers of countries experiencing terrorist attacks: 86 countries recorded an improvement, compared to 19 that deteriorated.

Secondly, the fall in deaths was mirrored by a reduction in the impact of terrorism, defined as the numbers of countries experiencing terrorist attacks: 86 countries recorded an improvement, compared to 19 that deteriorated.

More importantly, the report highlights a shift in the dynamics of terrorism, with terrorism becoming more concentrated in regions and countries experiencing political instability and conflict.

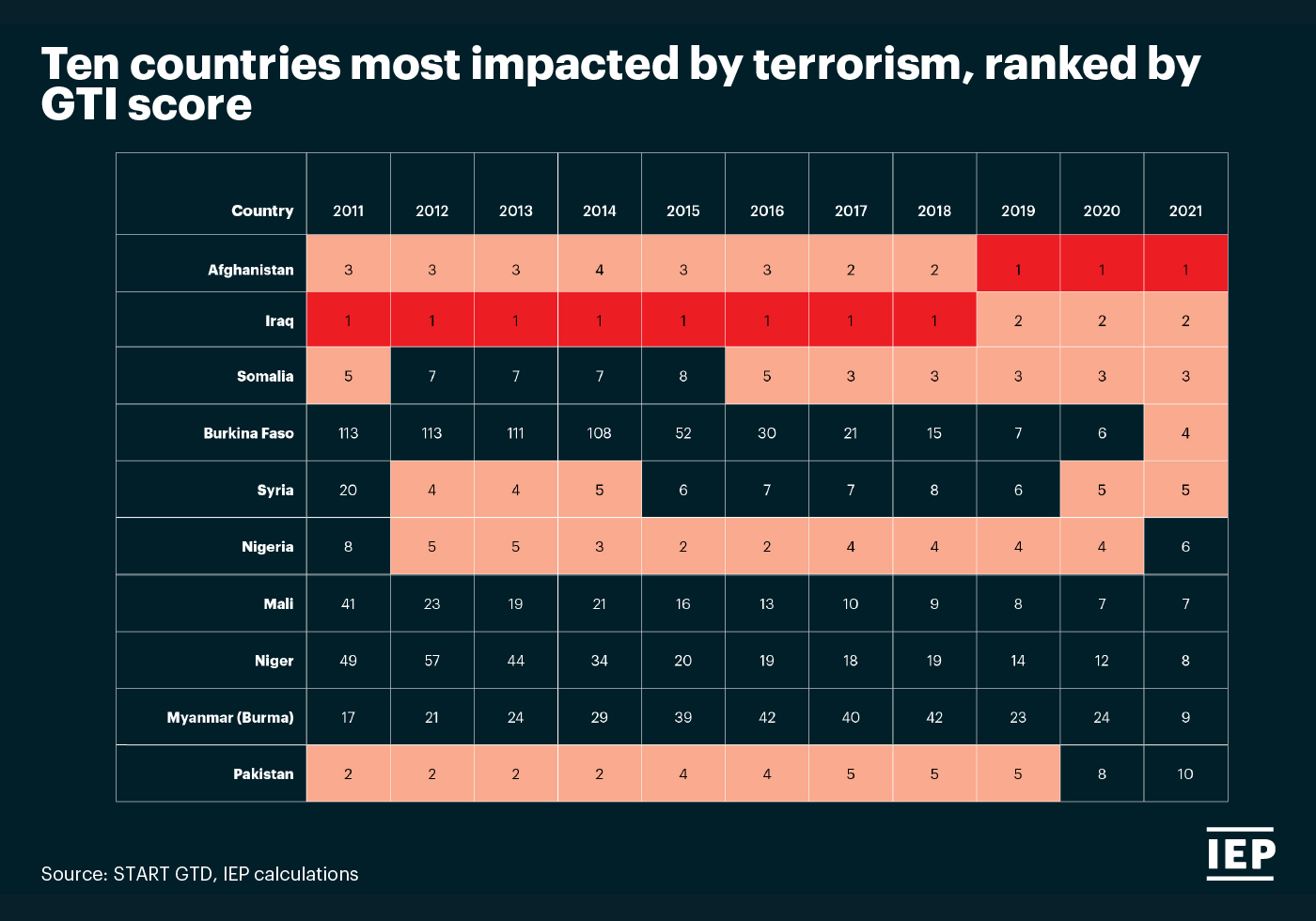

Violent conflict remains a primary driver of terrorism, with over 97% of terrorist attacks in 2021 taking place in countries experiencing some form of conflict. All of the ten countries most impacted by terrorism in 2021 were involved in an armed conflict in 2020. Attacks in countries involved in a conflict are six times deadlier than attacks in peaceful countries.

Afghanistan remains the least peaceful country in the world for the fourth consecutive year.

Global Peace Index rankings: https://t.co/ieTEZsSJdc pic.twitter.com/J7xjz0i0xn

— IEP Global Peace Index (@GlobPeaceIndex) April 8, 2022

Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia – all countries either directly involved in conflict or emerging from war:

However, in the list, there is something new emerging: Woven into the analysis is the recognition that the security situation in many in Sub-Saharan countries is deteriorating, as Salafi-jihadi activity rises.

However, in the list, there is something new emerging: Woven into the analysis is the recognition that the security situation in many in Sub-Saharan countries is deteriorating, as Salafi-jihadi activity rises.

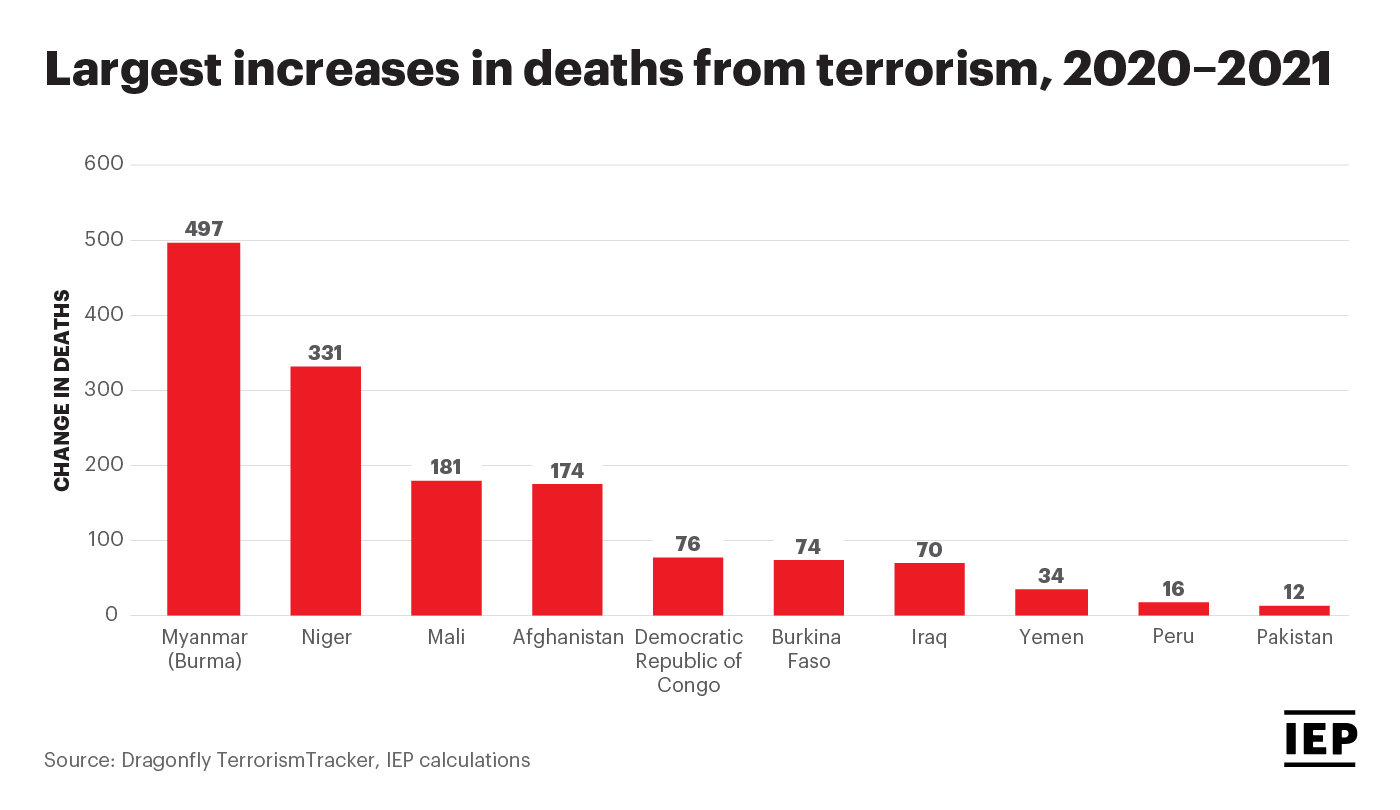

Nearly half of all terrorism deaths globally (48 percent or 3,461deaths) occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa. Four of the ten countries with the largest increases in deaths from terrorism were Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, and Niger, all of which are fragile states scoring very low on the Positive Peace Index. Fragile states are characterized by a lack of social and economic resilience to outside shocks, as state institutions are often new and poorly grounded in local society and communities often have not yet formed their own associations.

Salafi-jihadi terrorism is hitting the Sahelian countries

Salafi-jihadi terrorism is hitting the Sahelian countries

The 2022 GTI underlies the need to focus on the Sahel, with the data showing that the region is grappling with rising Salafi-jihadi activity. What magnifies the threat posed by Salafi-jihadis is that many Sahelian countries are already highly fragile, which means their ability to withstand crises is very limited.

Moreover, the recent decision of France to end its decade-long counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations in Mali does not bode well for regional security, as questions remain as to the ability of Sahelian countries to resist and repel Salafi-jihadism.

The Sahelian Salafi-jihadis seem to have adopted a two-prong strategy.

Firstly, they look to create a permanent state of instability and insecurity as a way to undermine the existing political order. At the same time, they also look to ingratiate themselves with the local communities by offering basic services such as human security.

If the Salafi-jihadis cannot win local support, they revert to terror, as ISWAP recently did when its members killed 24 villagers because ISWAP claimed they had helped the Nigerian military.

In a region where youth unemployment is high and salaries are low, these entities can entice young men to join them.

For example, Boko Haram is said to have exploited the pervasive poverty and lack of opportunity in Northern Cameroon by giving young men a choice: join the group or stay at home and do nothing while their families live in abject poverty. Boko Haram offered between US$600 – US$800 each month, whereas those lucky to get a job could, at best, earn US$72 a month.

In response to ecological changes that are increasingly impacting substance and rising insecurity – both of which are intrinsically linked – some governments have turned to ethnicisation policies which translate to giving preferential treatment to one ethnic group over the next. This in turn leads groups to either abandon their ancestral homes or form militias to defend themselves.

What happened in Mali and Burkina Faso illustrates the problem.

In Mali, the failure to address the crisis in northern Mali has led to intercommunal violence in the Mopti and Ségou regions between Dogon and Fulani, with the Malian government favouring the Dogon who are sedentary farmers, whereas the Fulani are semi-nomadic cattle herders.

Related Articles: Why We Need a New Definition of Peace – Peace in the Age of Chaos – Interview with Steve Killelea

In Burkina Faso, tensions between Fulani and Djermas have encouraged some Fulani to turn to groups called Ganda Izo (“sons of the soil”) or to the Islamic State in Greater Sahara or Ansarul Islam, as they look for protection and support.

There is clear evidence that the strategy taken by Salafi-jihadis is paying dividends – over the last 18 months, there have been eight different attempted military coups in the region, five of which succeeded in replacing the civilian government.

The militaries defended their actions because their take over came about because of the need to restore security, which is why in Burkina Faso, for instance, the military coup was supported by many civilians, agreeing that the civilian authority had proven incapable of stopping the Islamists.

The GTI report also highlights that Salafi-jihadis tend to focus their activities around waterways and away from large urban centres. There was hardly any attack in any major city in the Sahel, as the Salafi-jihadis restrict their activities to the bush where they can commit sneak attacks or carry out ambushes.

Focusing their attention on these areas has enabled Salafi-jihadis to exert more power on local communities.

In 2012, Salafi-jihadis exploited structural weakness within Mali to launch a powerful offensive that saw them establish, albeit for a short time, the Islamic Emirate of Azawad.

As conflict in Ukraine dominates global attention it is crucial that the global fight against terrorism, particularly in fragile states, is not sidelined, undermining all of the hard-fought battles of the last two decades.

— —

The Global Terrorism Index (GTI) is a comprehensive study analysing the impact of terrorism for 163 countries covering 99.7% of the world’s population. The GTI report is produced by the Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) using data from Terrorism Tracker and other sources. To read the full report, click here.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: The Global Terrorism Index 2022 cover page. Featured Photo Credit: IEP.