The facts are harsh and give Europe a catastrophic image to the world: The Ukraine crisis should be – geopolitically speaking – a uniquely European crisis involving directly European powers and the fate of millions of Europeans, yet it is handled by America. Why? Because Europe is unable to speak in one voice. The European Commission’s chief diplomat, Josep Borrell, may well participate in most meetings but his participation (so far) has made practically no difference.

The Ukrainian crisis has put the spotlight on all the weaknesses of the European Union when it comes to diplomacy and handling issues beyond its borders. As Russian troops build up along the Ukraine border, the emergency is upon Europe. It is about the future of Europe itself as a geopolitical power – as potentially the third big power in the world standing between America and China, given its economic might.

After all, consider that Russia’s economy is only about the size of Italy’s – a medium economic power. So why should Russia matter so much?

What makes Russia so dangerous to world peace are Putin’s dreams of restoring Russia to the glories of its Soviet past. Consequently, Putin has ramped up and modernized its army and armaments; he has pursued a policy of conquest abroad, forcefully annexing Crimea in 2014 and establishing a strong presence in Syria and the Middle East; he has secured an enduring alliance with China, notably through building the new “silk road” across the Arctic, now that the ice is melting as a result of climate change.

And finally – a cherry on the cake – Russia, an oil and gas power, controls 40% of Europe’s energy sources.

On Friday, January 28, French President Macron and Putin spoke by phone for more than an hour about Ukraine. Afterward, a senior official in the French presidency told a New York Times reporter, speaking on the condition of anonymity, “Dialogue with Russia is not a gamble, it’s an approach that responds to a necessity.”

What necessity? Macron has no doubts: For him, Europe needs to speak with one voice and achieve “strategic autonomy”. Later, the same day, Macron spoke to the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, reaffirming solidarity with Ukraine making it clear that he means to play the role of key intermediary.

From the start of his presidency, Macron pushed his view of a strong Europe making its weight felt on the international scene and he promised that, in his role as the leader for France, he would do everything to make it happen. In a landmark speech at Paris’ Sorbonne University in September 2017, he outlined a six-pillar plan (he calls them “keys”) to reform Europe and make it “sovereign, united and democratic”. And he is willing to gamble his re-election on that promise. Hence the phone call with Putin, a call that is making Biden and the Americans nervous, as the implication is that a solution to the Ukraine crisis could take place outside NATO and hence, outside America.

This unilateral French attempt to “solve” the Ukraine crisis came on top of a “Normandy Format” meeting held two days before in Paris, on January 26 – the said “format”, an informal forum calling together the main contenders Russia and Ukraine with France and Germany in the role of peace-makers.

Again, nothing notable resulted from the talks. Except perhaps for two things:

- one, according to Andriy Yermak, Ukraine president Zelensky’s representative, there was a “unanimous agreement” that the cease-fire in the oriental region of Ukraine should be respected; and

- two, they agreed to meet again in Berlin, two weeks hence.

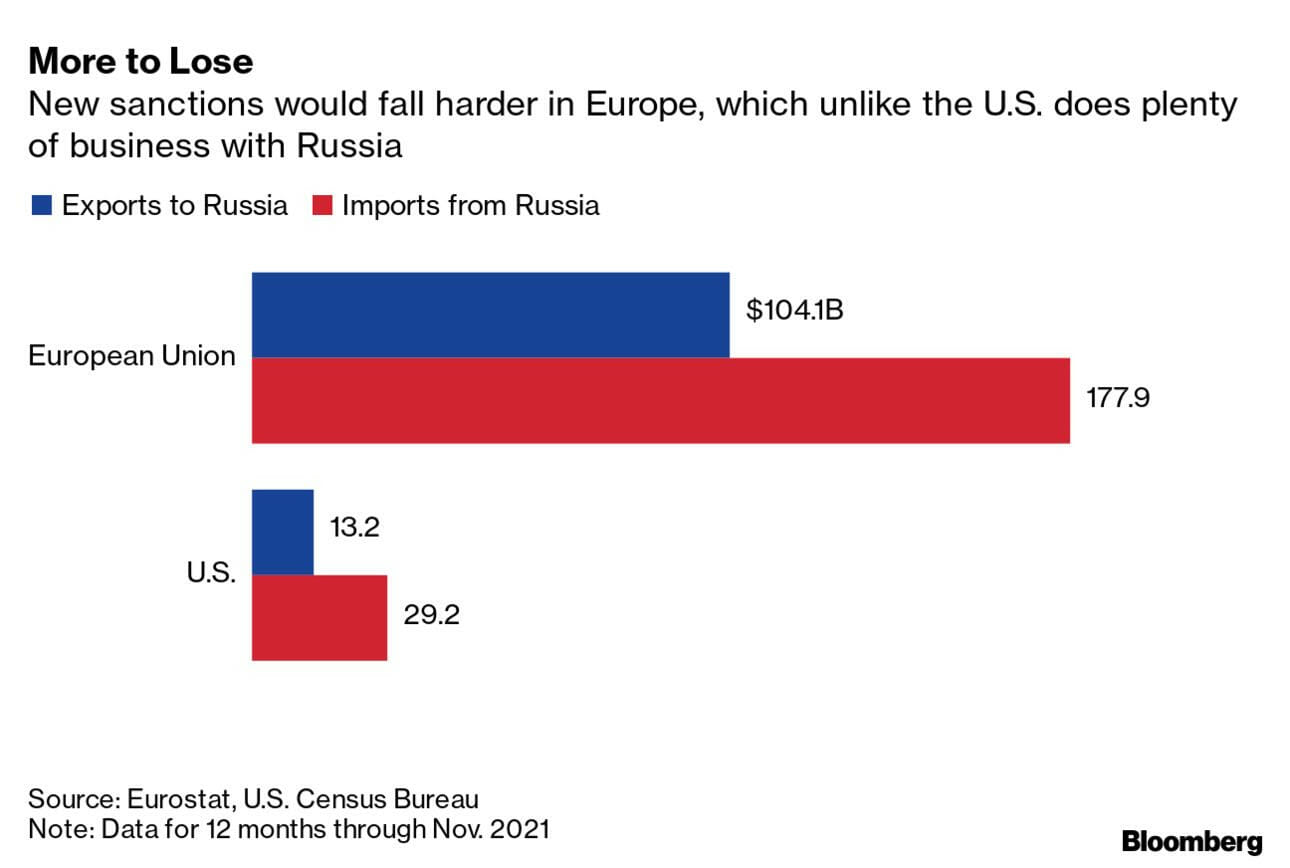

Nobody in Europe really welcomes America’s leadership in this case, seeing it as a form of meddling that could lead Europeans to be forced to take dangerous sanctions – sanctions that are far more damaging to Europe than America as Europeans are far more exposed. They are highly dependent on Russia’s gas and oil and heavily trade with Russia, much more than the US as this diagram clearly shows:

So where do we stand now?

As announced by Blinken, the American top diplomat in the talks with Russia, after his meeting with the Russian Foreign Affairs Minister Lavrov last week, the US sent a letter to Moscow offering a “diplomatic path forward”, with proposals aimed at addressing some of Moscow’s security concerns. The document reportedly calls for “reciprocal transparency measures regarding force posture in Ukraine, as well as measures to increase confidence regarding military exercises and maneuvers in Europe,” Mr. Blinken, the top American negotiator said, as well as nuclear arms control in Europe. He added, “It reiterates publicly what we’ve said for many weeks.”

Also this coming week NATO is reportedly going to send a letter to Moscow, presumably in line with American demands. While details about all those proposals are not available, they are certain to fall short of Russia’s key demand that Ukraine never be allowed to join NATO. In short, expect another standoff. Not surprising given the tactics of American diplomacy which consist in making public what their “red lines” are ahead of talks – something clever negotiators never do.

And this takes us back to the sanctions as the only way to handle the issue since nobody in the West, least of all America, wants to send their own troops to Ukraine or participate directly in any military operations. True, the US has put up to 8,500 troops on alert for possible deployment – not a consistent number by any means even if it can be viewed as a real deterrent. So the recourse to penalties and sanctions is likely unavoidable, and it is also precisely what Europeans do not want.

For a while, this week, it looked like Macron’s tough and independent line was his alone, that nobody was ready to follow him. Entrenched differences in views and sensitivity could be observed across Europe, from Viktor Orbán’s Hungary and Mateusz Morawiecki’s Poland traditionally wary of Russian ambitions to liberal countries like Sweden and Finland flocking under the umbrella of NATO, pushed by Russia’s aggressive stance. An example of the high fragmentation of European views on the matter also came from Italy where some business leaders have made the European Commission nervous (and angry) by holding a video meeting with Putin in the heart of the Ukrainian crisis.

Perhaps the biggest challenge to Macron’s proposed line of action had been Germany itself, notoriously unwilling to rock its (lucrative trading) boat with Eastern Europe in general and Russia in particular.

But then Macron and the new German Chancellor Olaf Scholz met in Paris on January 25 and things changed. Macron was finally able to announce what he wanted to say all along: that Europe is preparing “a common response” in case of Russian aggression.

The old Franco-German alliance that has so often guided the EU was restored and the two leaders aligned themselves on a working mixture of high-minded calls for principles with realpolitik caution: Scholz went so far as to say that Russia would pay “a high price” for any offensive in Ukraine, but in the meantime, acknowledging it was also necessary to follow the “path of dialogue”. And Germany (so far) has remained immovable on its position that it would not send arms to Ukraine, that diplomacy was its preferred way forward.

Hence, with Germany back in the French camp, the telephone conversation the next day between Macron and Putin, in continuity with this newly established “path of dialogue” and objective of bilateral negotiations between the EU and Moscow.

There are even rumors circulating that the US might be invited to participate in the next round of Normandy format talks – if so, it would make sense to invite America, as it is indeed an ally, but it should not be considered the leader in a crisis that is entirely European, nor should it be allowed to try and solve it without direct European involvement. The Normandy format talks solved the Ukraine crisis in 2014, they could do it again.

But we need to draw lessons from this experience.

In fact, all these months as the Ukraine crisis unfolded, we were made aware more than ever before of the steep price we could pay as Europeans for allowing the EU to remain marginal in the chorus of nations. For not pushing Europe to take its rightful place among the big powers and letting America decide on its fate.

The vacuum of strategic autonomy highlighted by Macron touches a raw nerve in the building of Europe: It’s high time Europe stopped being so fragmented and took in hand its own destiny. It should speak with a common voice and back it up with a common military force. Failing that, the EU appears destined for permanent geopolitical marginality.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Government officials arriving at the “Normandy format” talks held in Paris January 26, 2022 Source: Screenshot WION video